For months now, Serbia’s universities have remained occupied. Not by administrations, but by the students themselves. In a country where institutional neglect often fades into the background, a moment of collapse brought everything into focus. A railway station canopy in Novi Sad gave way. People died. The structure itself became a symbol: of shortcuts taken, of questions unanswered, of systems built to serve everyone but the public. From that point, something shifted.

What followed wasn’t chaos. It was order. Students across the country began organizing, not through political parties or appointed figures, but through conversation. In silence, they gathered. And then, they stayed. One by one, faculties blocked their buildings and froze their semesters, choosing to hold space rather than relinquish it. The occupation spread through entire cities. From Belgrade to Novi Sad, Niš to Kragujevac, lecture halls became sleeping quarters, classrooms became storerooms, and libraries became meeting points for plenums: fully democratic assemblies where every student could speak and vote.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

The demands are clear. Transparency. Accountability. Safer public infrastructure. Increased funding for education. A refusal to let violence, whether physical, administrative, or otherwise, go unanswered. But beyond the demands, something else has taken root. A culture of collective responsibility. These faculties now operate like autonomous communities. Roles are assigned for media, food, cleaning, and security, not by rank but by willingness. Donations are shared and logged. Nights are long, often restless. But the atmosphere is grounded, focused, and remarkably tender.

Seven months in, this movement is no longer about just one event. It has become a sustained experiment in agency. These are not idealists yelling into the void. These are young people who have redefined what it means to care for a public institution by inhabiting it fully: structurally, emotionally, and practically. They haven’t waited for change to be granted. They’ve started making it themselves.

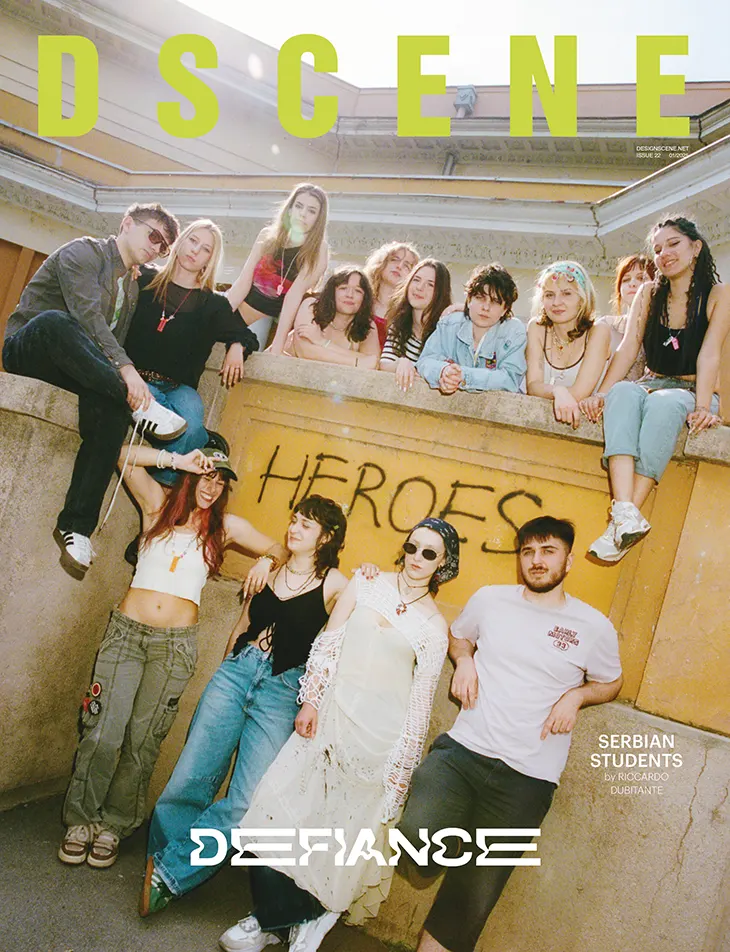

DSCENE spent time with and photographed students in Belgrade, where the atmosphere inside the occupied buildings speaks to something far deeper than protest alone. Among sleeping bags, posters, and half-finished canvases, we found a quiet intensity. It’s not loud, but it’s unmistakable. What these students have built is more than a protest. It’s a prototype. A different kind of future, practiced, every day, in real time.

Editor Katarina Doric met with the students inside the occupied faculties, where daily routines have become expressions of resistance. Between night shifts, plenums, and shared meals, they spoke about the systems they’ve created, built on trust, coordination, and shared responsibility. They described a space where decisions are made collectively, and where protest is sustained through quiet focus rather than spectacle. Photographer Riccardo Dubitante documented these moments, capturing both the protests and the occupied university spaces with intimacy and precision.

What kind of Serbia are you fighting for? – We are fighting for a country that is just and fair to everyone. Free of corruption, where its laws and constitution are respected and not twisted by the ruling regime.

We have six student demands that need to be fulfilled for our protest to end:

- Publishing of the entire documentation for the reconstruction of the train station in Novi Sad that is currently unavailable to the public.

- We demand identities of people that attacked students and professors of the Faculty of Dramatic Arts during their peaceful 15 minutes of silence protest in memory of the victims from the Novi Sad railway station. We also demand that these people are indicted and, in some cases, dismissed from their public posts.

- Annulment of charges against people arrested at the protests.

- We demand a 20% raise in government funding for university-level education.

- Thorough and detailed investigation into the alleged use of a sonic weapon during the mass protest on the 15th of March in Belgrade.

- Responsibility for protection of patients.

How do you feel after seven months of protest? – After seven months of constant protests, we feel like we live in a drastically different country, where its people set aside their differences, united against problems that plagued Serbia for far too long.

What does a typical day look like now inside the occupied universities? – Every university changed a lot during our occupation. What were once classrooms are now living quarters, workshops, lounge areas, storage spaces, etc.

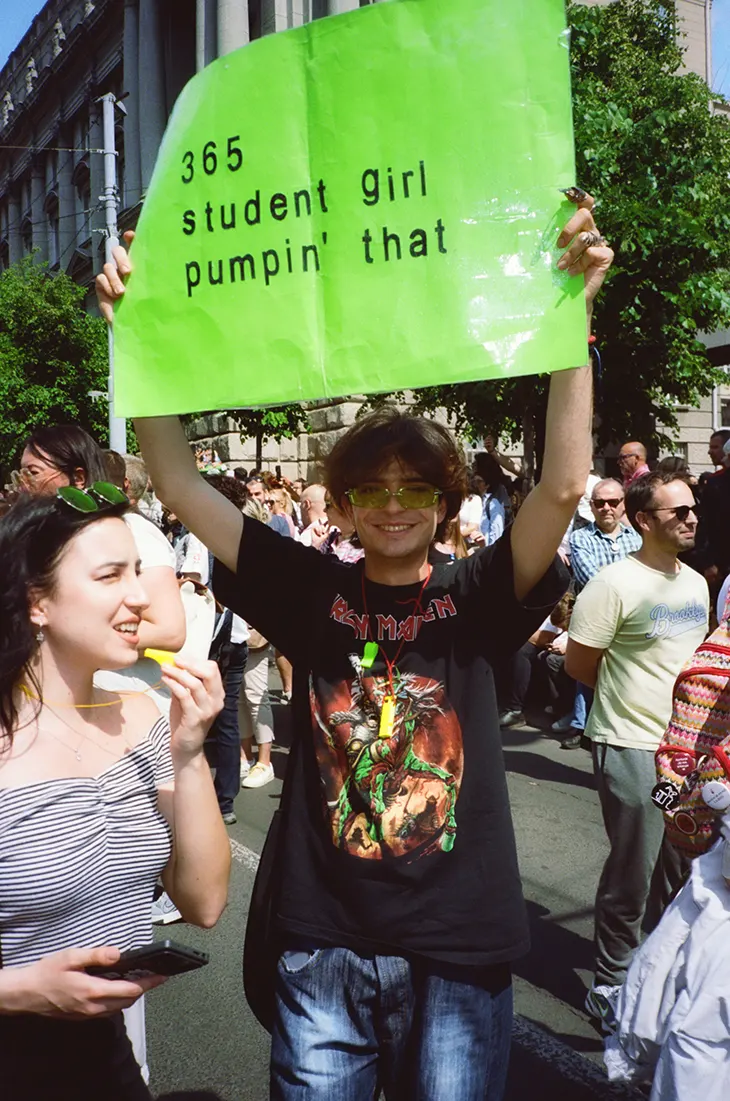

All faculties added handmade signs, banners, and placards on the outside of their buildings. These happened spontaneously, therefore every faculty did its own ‘thing’ and added different slogans, messages, and questions pointed at our government. These also had passing trends that changed from time to time and are some of the ways we communicate to passersby what our student demands are. Rarely, these signs would get vandalized, so we just hung new ones or placed them higher so no one could reasonably reach them.

We receive a lot of donations in the form of food, materials for arts and crafts, hygiene items, monetary donations, or some other forms of help. After receiving donations, we immediately separate them into different storage compartments.

How people spend their day really depends on which faculty they are blocking. We all formed unique communities with rules specific to their faculty. Most students volunteered to be in ‘work groups’ which are roles like security, media management, cleaning, etc.

Most of the time we are either doing research, reading, drawing, or enjoying internal group activities that we organize on a weekly basis. These activities are open to all students or even to the public. These activities are usually themed around the faculty they are held on or the student blockades themselves, which formed their own kind of subculture.

Since we block the buildings overnight, some students opt to stay there and sleep in our makeshift dorms. During our night shifts, usually there are more people guarding the entrances.

Of course, it isn’t all work. During these seven months, all of us attended a lot of birthdays, had fun, and made a lot of new friends. Although with this in mind, alcohol and cigarettes aren’t allowed on faculty grounds in any way.

How has this experience shaped your sense of community? – Since we spend most of our time together, all of us gained confidence, empathy, love, and respect for each other. All of us became more social, easygoing, and more aware of each other’s needs and values. A huge number of students are used to living alone or with a roommate, so taking responsibility to keep the faculty clean and doing chores wasn’t that big of an issue.

We haven’t waited for change to be granted. We’ve started making it ourselves.

How do you make decisions collectively, and what has that taught you? – We employed the system we call plenum – an absolute democracy where everyone gets to vote. A few people are chosen to be moderators but are usually swapped between meetings. Absolutely everything is voluntary, and everyone is invited to participate. Their time and place are known to every student of their respective faculty so they can join the next plenum at their faculty. Everyone’s vote matters equally, and every decision is given an ample amount of time to be analyzed and then later voted on. Usually, they last a few hours and can be exhausting. We sometimes agree to take a 15-minute break to refresh ourselves after an hour or two of discussion.

Every faculty has its own rules on how their plenum works, but in general, it works like this:

- Moderator presents in detail the topic of today’s plenum;

- Discussion begins, where everyone who wants to speak raises their hand and has around two minutes to present their idea, argument, or rebuttal. This time usually isn’t fixed, but if everyone thinks they need more time to explain, the moderator puts it to a vote to extend the timer for another two minutes;

- Everyone votes ‘in favor of,’ ‘against,’ or ‘indifferent’ by raising their hand.

How did you decide to block the university? What were you expecting to achieve? – The Faculty of Dramatic Arts was the first to block their university. By doing that, they effectively froze their semester, which created a major bureaucratic problem for the Ministry of Education. Other faculties soon followed. We all wanted change, so every faculty organized an internal plenum of their own. Every plenum voted in favor of the blockades. It’s safe to say that nobody expected it to last this long, but every faculty is open to ending the blockades if the majority of students wish to do so.

We were, and still are, expecting to achieve the same result as in the beginning – we want our government to fulfill our student demands.

There is no leader. There is a community.

What kind of support are you receiving and where is it lacking? – A lot of people showed us support through donations, attending protests, and support on social media. Where it’s lacking is when people only support us vocally, leaving the work to us while never really doing anything for the good of the whole.

Have any specific moments over these months felt like turning points for the movement? – There were days like the 15th of March that felt like a historic moment, with more than 275,000 people attending the protest. With that in mind, we know that the majority of people see that our intentions are pure – we fight for what is right and what the majority wants.

We had massive gatherings in all of Serbia’s major cities, cycled to the European Parliament, ran a marathon to Brussels, and received support from all over the world. Everywhere, we were welcomed with open arms. Our movement only kept growing. Every attempt by the government to strike fear into us failed due to the sheer number of people who stood behind us.

Even things that initially seemed frightening ultimately worked in our favor. Every lie and action they took to discredit us only added to our momentum.

We are fighting for a country that is just and fair to everyone. Free of corruption, where its laws and constitution are respected and not twisted by the ruling regime.

You have crossed cities on foot, cycled to the European Parliament in Strasbourg, and run a marathon to Brussels. What do these acts of endurance and movement represent for the struggle, and what message are you sending? – The message is quite clear – we believe in our cause. We wanted to spread our message and our story to as many people as possible. The more people hear and understand our words, the stronger the message becomes. Most of the people we encountered along the way welcomed us or wanted to hear our side of the story. Most people we crossed paths with in Serbia can only be informed through biased, government-approved media, so seeing us actually taking on such arduous tasks made them reconsider their opinions.

Do you believe the government underestimated you? What do you think they still don’t understand? – Our government is trying to play the long game, trying to dismiss our peaceful protests as tantrums, acts of terrorism, or foreign manipulation. They claim we don’t fully understand what we are asking for or that our demands have already been met. They underestimated our willingness to stand for what we believe in and our refusal to be scared off, bribed, or manipulated into giving up before we decide it’s time.

They simply do not understand where our morale, courage, and will come from. They think we are naïve and short-sighted.

The system failed us. We’re building a new one.

How do you deal with attempts to delegitimize the movement by political actors or mainstream media? – Ignoring provocations most of the time gets the job done. The less attention they get, the sooner they move on to something else that simply won’t work. Again.

In moments of fear or exhaustion, what keeps you going? – Looking back, we accomplished record-breaking events for Serbia. It’s not that nobody could do it, it’s that nobody believed everyone would get on board. We had perfect timing, and with the system of plenum, we can think carefully about every next step.

What small acts of defiance do you think matter most, even outside of mass protest? – As cliché as it sounds – perseverance and believing in ourselves, not falling for obvious traps and provocations, sticking to the truth, and believing in a brighter tomorrow. Boosting morale and not letting go of our ideals and goals. People who are against our movement often simply ignore it or try to provoke us. We are always open to discussion and critique and always take the time to talk with people. Often, we even get them to change their minds on things, but sometimes, people are too far into the process.

What would you say to people who think resistance is pointless or that change is impossible? – People who accept the status quo as unchangeable should start by at least questioning themselves. Now more than ever, it’s possible to act on the things you don’t like about living here.

We will keep giving it our all. Change isn’t impossible, change for the better has already happened in Serbia. With everything constantly evolving, people forget where we were just seven months ago.

Things have changed, but they are far from over.

In moments of fear or exhaustion, we look back and realize — it’s not that nobody could do it, it’s that nobody believed everyone would get on board.

Looking forward, what are your expectations? – Our fight for a better tomorrow has only just begun. Student protests will eventually end, but that doesn’t mean the fight is over. We risked our school year, our future, and our safety so we could have a better place to call home. Eventually, every regime falls, and then we will have to pick up what’s left of our country and rebuild it. We want a future for ourselves in Serbia, because we want to live in our own country.