Brett Charles Seiler’s paintings are a deeply personal meditation on intimacy, memory, and Queer identity. In conversation with Zarko Davinic for DSCENE Magazine’s art pages, Seiler opens up about the autobiographical nature of his work, where each canvas becomes a site for exploring desire, anxiety, and the evolving dynamics of private and public life. His practice is marked by a distinctive fragility, both in the way he renders the male body and in his use of ephemeral materials that evoke nostalgia and vulnerability.

With a background rooted in Zimbabwe and a career spanning exhibitions across Africa, Europe, and the US, Seiler’s art draws from a rich tapestry of cultural references and personal experiences. His approach to painting is intuitive, often starting with photographs of friends and lovers and unraveling into layered narratives that balance the personal and political. Whether referencing Queer history, Biblical symbolism, or domestic interiors, Seiler’s compositions invite viewers into spaces that are at once familiar and unsettled.

In this exclusive interview, Seiler reflects on the evolution of his visual language, the role of humor and text in his work, and the importance of empathy and sensitivity in representing the male figure. His candid responses reveal a practice that is as much about self-discovery as it is about forging connections, with history, with community, and with anyone who might find resonance in his stories.

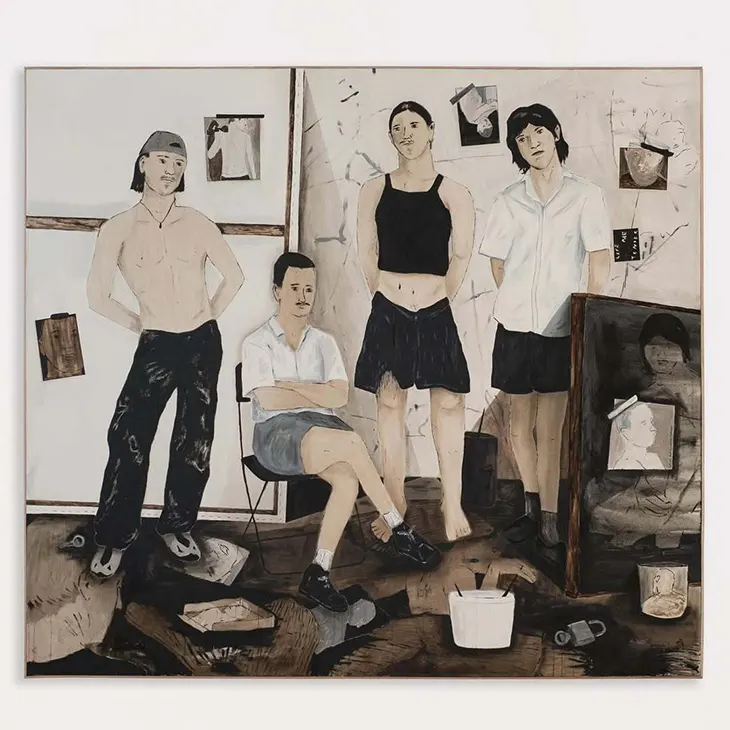

Your paintings often oscillate between desire and anxiety, exploring themes of Queer history, Biblical symbolism, and domestic space. How do you decide which narratives or symbols to foreground in a new body of work? – The work being so autobiographical, it really depends on the start of the painting and how it unravels. I think critically over it for sometime in the beginning stages of the painting and often or not, it becomes a mashup of all of the above. Recently, I have been painting friends and lovers in my studio – a place of work, i see a shift of the works talking about relationships and dynamics, private vs public.

The male body is a recurring subject in your practice, rendered with a fragility that feels both intimate and ephemeral. What draws you to this particular representation, and how do you see it evolving in your future work? – Representing the male figure in this very delicate way is an act of queering, to make something tender, especially with using such a tough material like Bitumen which is hard to manipulate. I try to use less lines, more washes, to make me feel as if something is fading away – sort of like a distant memory. This adds to the nostalgic qualities of the painting. I like how broken the figures can seem, and in this way I feel as if there is a lot of empathy and sensitivity to the work.

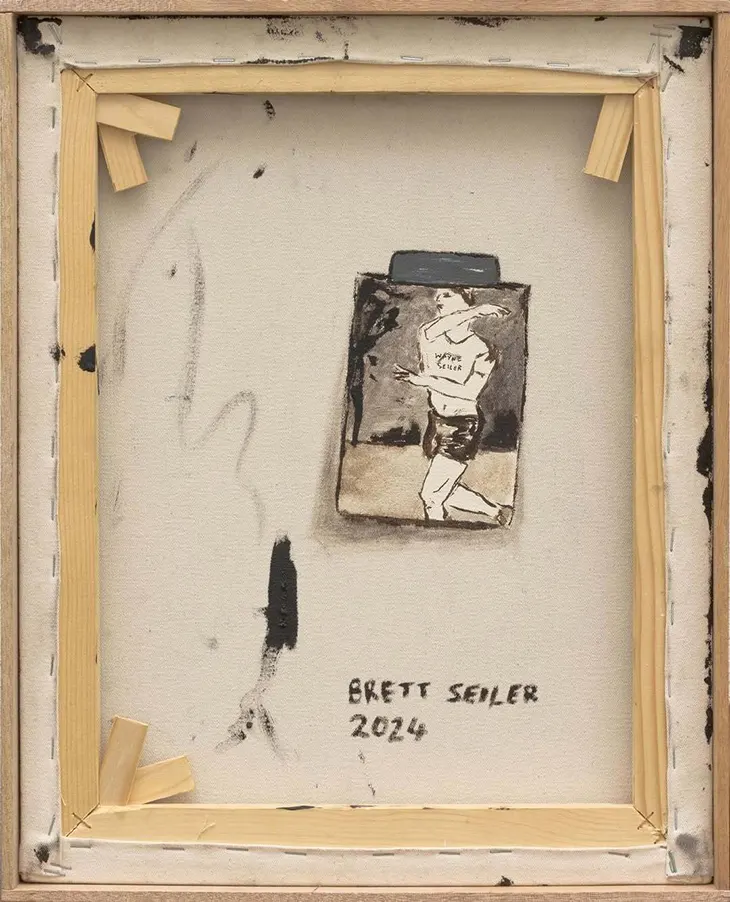

Your early works incorporated found objects like photographs and fabric, while your recent paintings focus more on surface and line. How has your material experimentation shaped your visual language over time? – Photographs are always going to be constant in my work, I work from photographs of my friends/lovers that I study and paint from. Usually in black and white, so they also kind of feel like a found object. With my materials I use, they normally gravitate towards me such as suitcases, pieces of wood, things that often have a forgotten history to them, something domestic, dealing with storage or travel. I think it also has to do with my studio, i collect chairs and random books, and having them around me in the studio also provides some inspiration even if they don’t end up being part of the work.

I think the personal is political, they have all combined to this autobiographical work i have been doing up until now – with my previous work when i made black and white gay flagged stripped of colour to represent the loss of rights – it’s still in the painting, the painting being monochromatic – as if the life has been suck out of the painting, again this loss of something inside them.

Your work seems to draw on art historical references, such as studies of the male nude and motifs like paintings within paintings. Is this intentional, and if so, how do you see your practice relating to or diverging from these art historical traditions? – I think the poses can often seem quite historical, and it is definitely a reference to historical painting like from the renaissance for instance. Even with the paintings within the paintings, I like to think of it as a rabbit hole. The more references I have in my studio, the more they come out in the painting, reference each other and historical painting. When it comes to the male figure, it is quite easy to maybe look at it and make it somewhat ambiguous – so instead of having intense muscular bodies, they are more relaxed and androgynous.

Can you speak to your process of integrating language and image, and what it allows you to express that painting alone cannot? – When I do my text works, they are quite spontaneous – they have to happen in the moment when the statement comes to me – they are like diary entries. The text works often i feel accompany my figurative pieces, they somehow link up and create a narrative and association. Seeing them all bound together really makes a statement, something perhaps figures cannot do – and something words cannot do. By putting them together it creates a whole scene of what is happening.

The “Coke/cock bottle” appears as both a recurring object and a sculptural element in your work. What does this motif signify for you, and how do you use humor to navigate eroticism and vulnerability? – The coke/cock bottle has many different meanings but more so is a direct reference to queer artists like the poet Alan Ginsburg – Having A Coke With You, or Andy Wahol’s coke series. So the simple act of changing coke to cock, is a more camp fun way of presenting this consumer product. It then becomes a quick laugh but also kind of sweet, naive and honest. I think in queer culture, making fun of something is a political act, it’s taking something not as serious.

Much of your work addresses personal experience as a gay man, but also engages with broader political questions of gender and sexuality. How do you balance the personal and political in your practice? – I think the personal is political, they have all combined to this autobiographical work i have been doing up until now – with my previous work when i made black and white gay flagged stripped of colour to represent the loss of rights – it’s still in the painting, the painting being monochromatic – as if the life has been suck out of the painting, again this loss of something inside them.

Discover More DSCENE Interviews

In your recent series, domestic interiors appear altered or unsettled, shifting between familiarity and unease. What attracts you to exploring domestic spaces, and how do you use them to reflect both intimacy and uncertainty? – The domestic space is such a unique one, because it gives a sense of belonging and familiarity but distorting that in my painting, with hidden figures on the floor or unfinished notes, I guess makes the space more of a maze. These ‘hidden’ motifs often appear near a figure, below them or above them, which could perhaps be seen as a thought or distant memory out in the open. Placing these people in my paintings in awkward positions, not looking at one another, some at the audience, some turned away completely, makes a statement about relationships and dynamics.

To be oneself, it might be scary and vulnerable but I think that is the beauty about making work about queerness specifically. You will find that someone out there will relate.

Having participated in exhibitions across Africa, Europe, and the US, how have different cultural contexts influenced your work or the way audiences respond to it? – Seeing the world is so inspiring, I am really grateful for seeing Europe and experiencing a different way of life. How it has changed my work – perhaps i have seen more, met more people and taken things subconsciously, but I also see myself looking at my older work and reintroducing them into my new work and i think that’s what i am focusing on now – looking at my work with new eyes.

Looking back on your journey since graduating from Ruth Prowse School of Art in 2015, what advice would you offer emerging artists who are exploring themes of identity, intimacy, and marginalization? – To be oneself, it might be scary and vulnerable but I think that is the beauty about making work about queerness specifically. You will find that someone out there will relate.

Brett Charles Seiler is represented by Everard Read, for more of Brett’s work visit his Instagram @brettseiler.