I spent Orthodox Christmas with my grandparents this year. We stayed inside, the house warm from cooking and constant movement. We drank mulled brandy in small glasses, strong and sweet, the kind that slows conversation. We ate too much, as people do when the table becomes the center of the day rather than a break in it. The hours stretched. Nobody rushed them.

DORIC ORDER

I am trying to go more often now. Age changes the way time behaves. Days stop feeling abundant. Each one begins to feel like it carries weight. Being present starts to feel like an act of attention, a way of marking time while it is still available.

In the afternoon we sat with coffee. Thick coffee, poured carefully, steam rising slowly. Conversation moved without structure, drifting the way it does when nobody needs it to go anywhere. There was a tapestry on the wall, a white swan floating on a lake. It had been there for years, long enough to stop being noticed. My grandfather said it was made by his sister’s husband while he was in rehabilitation, decades ago. We spoke about it briefly. About patience. About how long it must have taken. About the steadiness of hands.

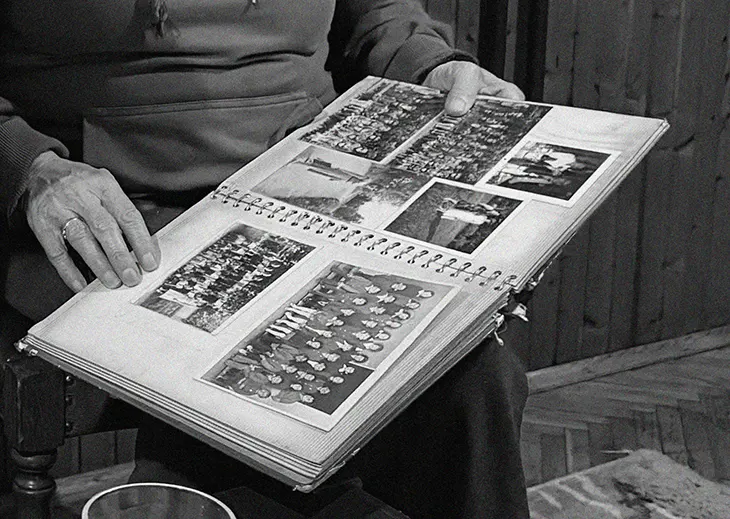

Then my grandmother paused. She looked away from the wall, as if something else had surfaced. She said she had carpets under the bed. Old ones. Made by my grandfather’s mother, many years ago. She asked if I wanted them.

Women often pass things on without ceremony, trusting recognition rather than explanation.

She did not explain why she was offering them now. She did not describe their value. She did not frame the moment. The sentence arrived plainly, as if the meaning required no elaboration. Women often pass things on this way, without ceremony, trusting recognition rather than explanation.

I said yes.

Outside, it began to snow.

At first it felt incidental. Then it thickened. Large, heavy flakes falling steadily, covering everything without urgency. At some point we realized we needed to leave if we wanted to get home. The streets would soon become difficult. Everything outside had turned white. Completely white.

It had not snowed like this in Belgrade for years. Not like this. Not quietly. Not completely. The city felt suspended. The snow erased outlines, softened edges, returned the streets to something earlier, something remembered rather than current.

I felt a pull backward, sharp and unexpected. The snow took me back to childhood winters, to silence, to days when time felt slower and the world felt contained. The timing sharpened everything. The carpets. The stories. The awareness that we were leaving while we still could.

Women pass down power without calling it power.

The carpets came out folded, heavier than I expected. Wool carries time differently. It holds warmth. It absorbs sound. It remembers pressure. I took them home quietly, placed them in the trunk, drove back through streets I knew well. I felt that something had shifted, though the shape of it remained unclear.

That evening I laid the carpets out in my living room. It settled immediately, grounding the space. The colors felt deliberate. The pattern felt resolved. I called my mother and showed it to her through the phone. She recognized it at once. She did not hesitate. She said the name of the woman who made it. My great-grandmother. Stanojka.

The carpet required no authentication. It carried its own lineage.

We talked for a long time. About Stanojka. About the way she lived. About what her life required of her.

She lost her husband during the Second World War and raised three small children alone, including my grandfather. They lived in a village on Radan Mountain, close to the border of Serbia and Kosovo. It was a place shaped by seasons and repetition, by distance and labor. Survival there depended on consistency. Food had to appear every day. Bodies had to be kept safe. Fear had to be managed quietly. She became the center because there was no other structure to rely on.

Men inherit land. Women inherit continuity

She became the matriarch without ever being named one.

In families like mine, inheritance rarely arrives as property. There are few documents. Few formal transfers. What moves instead are skills, habits, objects shaped by use. Women pass down power without calling it power. Through food prepared the same way every time. Through remedies learned by smell and touch. Through labor repeated until it becomes instruction.

When I was a child, Stanojka frightened me. She came to Belgrade once, very old. I remember her sitting in a chair placed deliberately in the center of the room. She wore black. A black dress. A black headscarf tied tightly. She held a walking stick. She did not speak much. She did not move much. Her presence felt dense, contained, authoritative.

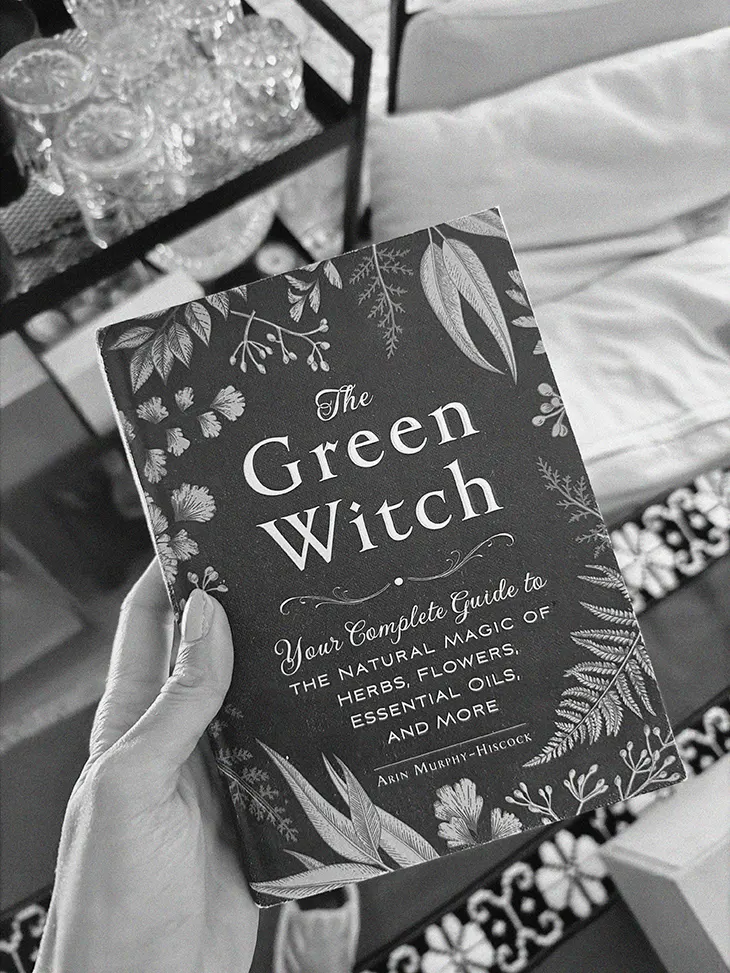

Later, my mother told me she had been strict. Among the children, stories circulated that she was a witch. This seemed logical at the time. She matched the image we had absorbed without context. Black clothing. Silence. Age. Authority.

Female authority forms quietly when there is no other structure to rely on.

I asked my mother about it. She laughed softly. She said Stanojka was a healer. She practiced alternative medicine. She knew plants. She made teas for everything. My mother said she still remembers their smell. Each one distinct. Each one purposeful. One for sleep. One for pain. One for fear. She said Stanojka had words she spoke when children became frightened. Quiet phrases. Repeated calmly. Learned through listening.

Nothing was written down. Nothing needed to be.

I said this sounded like a green witch. My mother agreed.

This is how women leave things behind.

There is no will. No estate. No formal recognition of labor that sustains life. What remains is continuity. Knowledge travels through repetition. Authority grows from care. Responsibility becomes structure.

The carpet now sits in my living room. It anchors the space. It absorbs sound. It holds the room together. It carries the work of a woman whose life never entered any archive yet shaped every life that followed hers. It holds discipline. Endurance. Practical intelligence.

What matters is rarely stored where it can be seen.

Textiles like this appear repeatedly in women’s histories. Rugs. Carpets. Embroidery. Blankets. Tablecloths. Objects created for use rather than display. They warm rooms. They dull echoes. They travel when women move. They survive war, relocation, marriage, borders shifting around them.

They wait.

Under the bed becomes a place of preservation. Women understand storage as method. What matters stays close to the body. Accessible. Protected. Unremarkable to outsiders.

Men inherit land. Women inherit continuity.

Stanojka dressed in black because mourning was not a phase. It was a condition. Losing a husband during wartime reshaped the rest of her life. There were children to raise. Work to complete. Fear to contain. Firmness followed necessity. Over time, firmness became language.

She practiced healing because doctors were far. Because institutions did not reach women like her. Because knowledge was local and immediate. Plants became medicine. Words became tools. Touch became authority. Children learned fear could be spoken away. That fear could be addressed without spectacle.

This form of power rarely receives recognition. It gets folded into folklore. It gets diminished as superstition. Still, families continue because of it.

What survives is what is repeated.

There is no institutional framework for this inheritance. It does not register as wealth. It resists classification. Still, it shapes lives with precision.

When my grandmother offered me the carpets, she trusted something without explanation. This is how women choose heirs. Through proximity. Through presence. Through recognition built over time.

I did not receive these carpets by asking. I received them by being there. By sitting at the table. By listening. By leaving only when the snow made it necessary.

The things women leave behind rarely announce themselves. They wait. They persist. They shape rooms and lives quietly, without documentation or reward.

The carpet does not explain itself. It exists, doing what it was always meant to do. Holding space. Carrying pattern. Absorbing time.

The things women leave behind shape rooms before they shape history.

When I look at it, I think of Stanojka sitting in that chair in Belgrade. Black against pale walls. Body tired. Presence steady. I think of women before her whose names dissolved before anyone wrote them down. I think of knowledge preserved through repetition.

Inheritance law recognizes ownership. What women leave behind recognizes responsibility.

I did not inherit wealth.

I inherited structure.

That feels enough.

wow what a beautifully written piece. Amazing reading katarina’s columns.

I can’t help but agree with Katarina, such a poetic piece. And there is such magic in knowing more about our families, and having something handed down from our grandparents.