What was the last piece of art you saw that completely took your breath away? Great art has the power to do this – to surprise us and to draw us into the world of the artist in such a way that we never see the world in quite the same way again. This kind of experience is rare, but unforgettable when it happens – so, here is our pick of just some of the world’s most fascinating pieces of art.

Read more after the jump:

Frida Kahlo

Self-portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States, 1932

Frida Kahlo is an endlessly fascinating artist – someone whose paintings constantly surprise. Self Portrait on the Border between Mexico and the United States is no different – it shows Frida standing at the centre of a delicate balance between the two countries. On the left is a giant pre-Columbian temple, while on the right it contrasts with a gigantic Ford factory, billowing smoke. The painting is full of yearning for Mexico –its traditions and its ancient culture, in contrast to the modern, industrial world shown on the right. A powerful and unusual painting that reveals more secrets with each viewing.

Marc Chagall

Birthday, 1915

Painted in 1915 after Chagall’s successful trip to Paris and as the First World War gripped Europe, Birthday is a beautifully intimate expression of a private moment between Chagall and his lover Bella. It is a strange and mysterious painting – the figure of the painter is curved up over and above the figure of Bella, clutching flowers in the apartment kitchen – and it almost looks as if she is being possessed by a spirit. But the flowing lines that Chagall used to paint himself actually represent the weightless feeling he experienced when Bella presented the flowers to him for his birthday –it is a beautiful expression of what it feels like to be in love.

Johannes Vermeer

The Love Letter, 1669

There is something almost photographic about Johannes Vermeer’s paintings. The light that fills them seems almost as if it could leak out from the canvas and his paintings often feel like little windows into another world or a scene viewed through a crack in a door. The Love Letter is a great example of this – but it is also a fantastic example of Vermeer’s ability to tell a story in his painting – the viewer is there, in the room, as the maid brings a letter to her mistress, and the painter has perfectly captured the moment of uncertainty on her face just before she opens it.

Courtesy of Tate Modern

Courtesy of Tate Modern

Ai Weiwei

Sunflower Seeds, 2010

This installation displayed in the vast Turbine Hall of the Tate Modern was remarkable if only for its attention to detail and the huge amount of effort and craft that went into creating it. 1,600 craftspeople worked for two and a half years to realise Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s vision – to create a space filled with one hundred million hand-painted porcelain sunflower seeds. It is a stunning work of imagination that celebrates the idea of art existing at every scale.

JMW Turner

Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth, 1842

This painting baffled many viewers when they first saw it and it is easy to see why. The looseness of Turner’s strokes are mesmerising, but it also obscures the subject almost to the point that it is hard to see. It was likened by one critic to ‘soapsuds and whitewash’ and in some ways that is fair comment – but it also completely misses the point. The power of this painting – and many of Turner’s other masterpieces – lies in this swirling use of colour and paint strokes. It is a wild and stormy painting of a wild and stormy moment in the artist’s imagination and has a huge amount of raw power, even now.

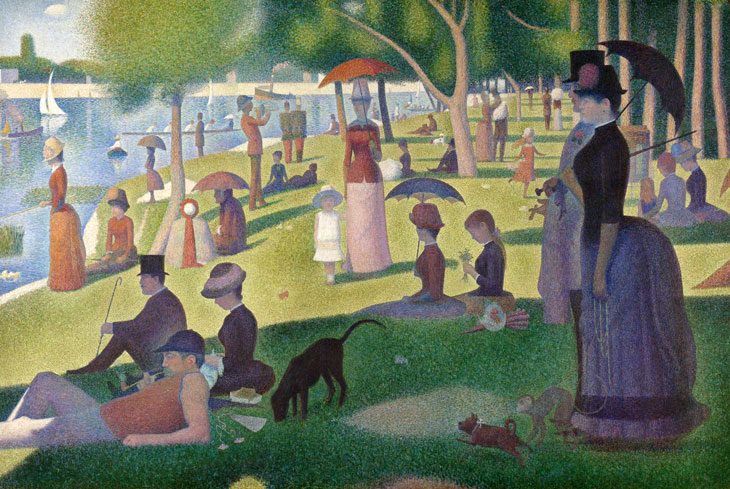

Georges Seurat

A Sunday on the Island of La Grande Jatte, 1884

From a painter who used broad strokes to one who specialised in tiny ones. Seurat was a pioneer of the pointillist technique, which used minute dots of paint to build up and impression of great bodies of light and shade and colour across the painting. This picture is a fantastic example of that technique and is one of those paintings that has the power to truly transport the viewer to another place.

Words by Jurg Widmer Probst