Spyros Rennt has spent the past eight years building a photographic language rooted in vulnerability, desire, and queer collectivity. Based in Berlin, the Greek photographer documents the emotional pulse of his community with a gaze that is both unflinching and tender. From underground parties to private moments, his images trace the fluid edges of connection – sexual, emotional, political. With To Kiss Against the Fire, Rennt traces a visual language shaped by years of documenting queer life. Held at Rosegarden, a new Berlin space by Frontrose and Frama, it marks a shift in his practice and signals the urgency of preserving queer narratives amid growing cultural pushback.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

In this exclusive DSCENE interview, Spyros Rennt speaks with editor Anastasija Pavić about the personal and political tensions that shape his work. The conversation traces themes of visibility and resistance, offering a glimpse into the emotional and ethical questions that define his artistic practice.

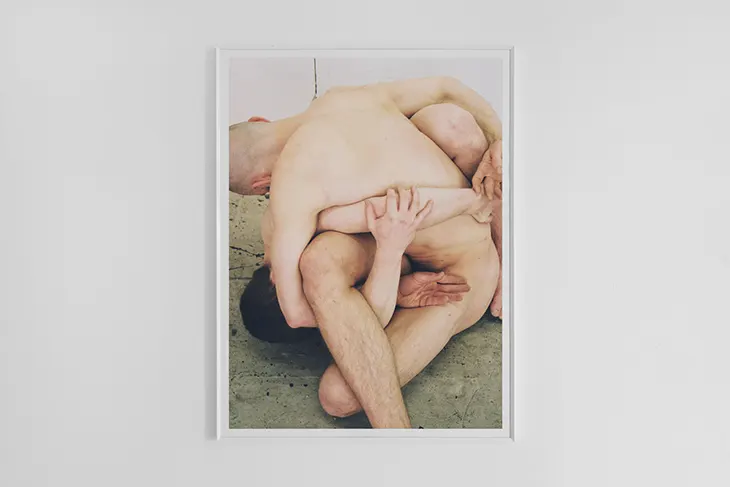

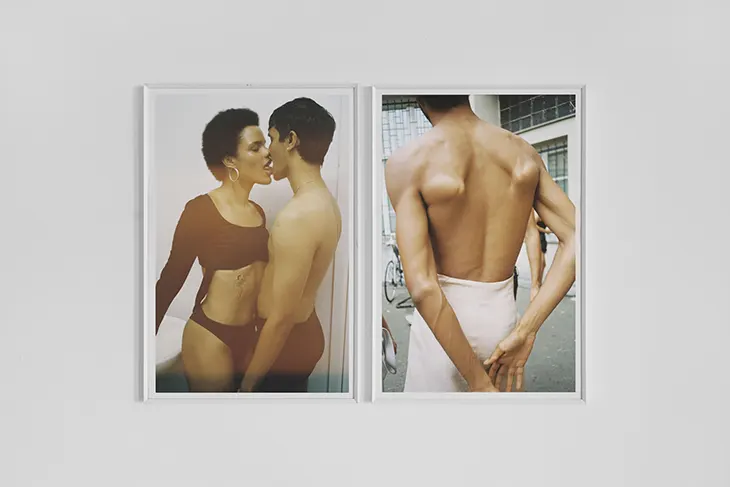

Your exhibition spans eight years of work and four books. What thread do you feel ties this visual archive together most strongly? – At its core, my work has always been about documenting the bonds between people, not as something constructed or performed, but as something lived. Across all four books and the years they span, the connecting thread is intimacy, often queer intimacy, in all its messy, soft, ecstatic, and sometimes fleeting forms. Whether it’s a tender glance or a wild night, I’m drawn to the emotional weight of the moment. That weight might shift across time and context, but the pulse is the same.

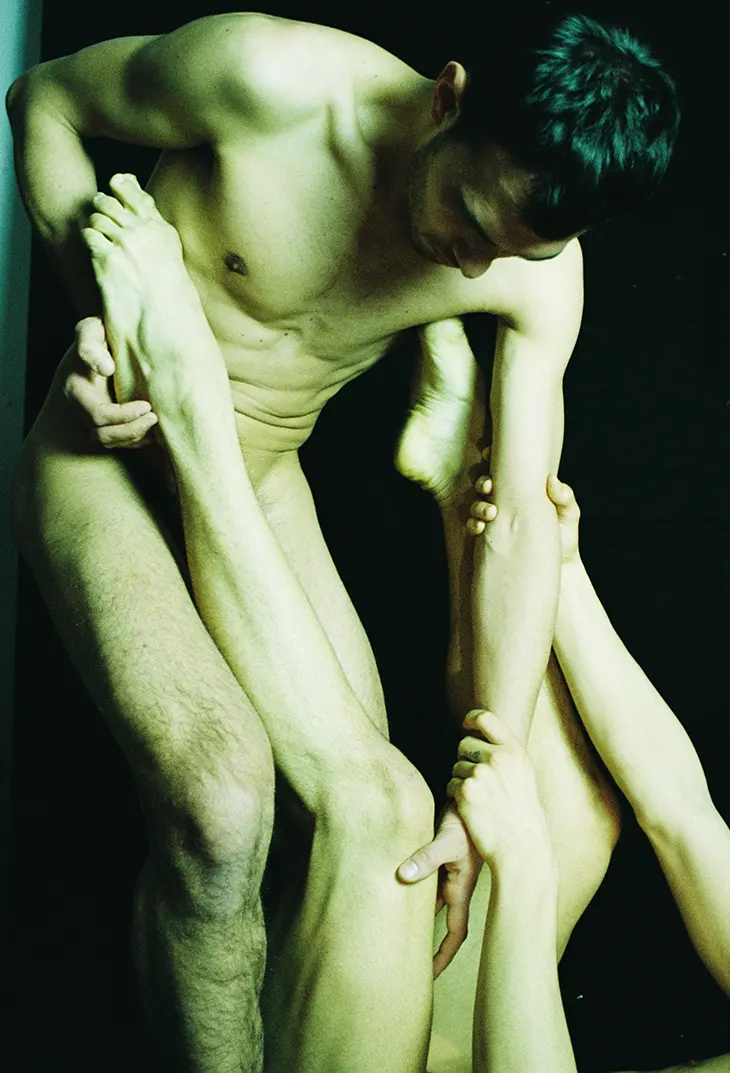

The title To Kiss Against the Fire references David Wojnarowicz. What does his legacy mean to you? – Wojnarowicz had this incredible way of turning rage into poetry. He made love a weapon and vulnerability a form of resistance. His work has always reminded me that tenderness and political urgency aren’t opposites, they can exist on the same page. The title To Kiss Against the Fire speaks to that: how queer love persists in hostile environments. It’s about surviving, but also about insisting on joy, connection, and beauty in the face of oppression and erasure.

Have your ideas about queerness and the queer community shifted through the act of documenting them? – Definitely. Photography has been a way of staying in conversation with the community around me and with myself. When I started, I think I was chasing an idea of queerness as sexual and emotional freedom. Over time, I’ve realized that queerness also means complexity, contradiction, chosen family, grief, caretaking. It’s communal and layered. The camera helps me stay present with that evolution.

With queer life so often under scrutiny, do you ever feel conflicted about what to show and what to protect? Does that come with a sense of responsibility? – All the time. There’s a constant tension between visibility and care. I photograph people I know, people I connect with, people I love; so I never want the image to take more than it gives. I try to create space in which people feel seen, not exposed. That means some photos stay private. But that’s part of the responsibility: knowing when the work should speak loudly, and when it should stay silent.

As queer spaces face erasure through gentrification and politics, do you view your photography as a way to keep their memory alive? – Yes, though I try not to be nostalgic about it. I want my images to hold memory, but also momentum. Queer spaces are not just physical, they’re emotional, ephemeral, built between people. If my photos can make someone feel that connection, even briefly, then the space still exists in some way.

In your work, bodies don’t perform for the gaze, they exist. How conscious are you of pushing back against traditional representations of queer desire? – It’s very conscious, but I’m not trying to “correct” the image of queer desire, I’m trying to expand it. We’ve seen so many flattened or fetishized versions of queer bodies in visual culture. I’m more interested in how desire actually feels in real life: sweaty, vulnerable, joyful, awkward, warm. When someone lets themselves be seen without performing, that’s where something real happens.

What is it like to be both behind the camera and emotionally present in the scene? – It’s a delicate balance, but I think that’s where the power of the image comes from. I’m not an outsider documenting a scene, I am a part of it. That closeness creates a certain honesty in the image. The emotional presence is what makes the moment matter.

What makes a moment feel courageous to document, even if it’s quiet or small? – Sometimes the quietest moments carry the most emotional charge. A look, a breath, a touch: these things can speak volumes if you’re paying attention. Courage, to me, is allowing yourself to be seen in those in-between spaces, without performing. When someone lets me witness that, and I choose to document it, there’s a kind of mutual bravery happening.

Does building a sense of fantasy in your images allow you to rethink narratives that often feel imposed? – Yes, definitely. Fantasy, for me, isn’t about escaping reality, it’s about rewriting it. Queer people have often had our stories told for us, or erased entirely. So inserting fantasy is a way of reclaiming authorship. It lets us reimagine our bodies, our relationships, our futures. Sometimes the most radical thing is to show ourselves in pleasure, in softness, in power, even if the world tells us not to.

What’s something you’ve outgrown creatively, and something you’re still growing into? – I’ve definitely outgrown traditional notions of beauty and perfection, both in terms of how I frame my subjects and how I see myself as an artist. Over time I’ve become much more drawn to what feels emotionally true, even if it’s messy, raw, or unresolved. I’m still growing into a space where imperfection isn’t just accepted but celebrated, where honesty takes precedence over polish. That shift has opened up so much more room for vulnerability, and for connection.

Originally published in DSCENE 022 “Defiance” Issue.