Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

Schiaparelli is a Parisian fashion house that has left an everlasting mark on the fashion world, mostly thanks to its bold, surrealist style. It’s founder Elsa Schiaparelli was one of the leading figures in the creation of fashion as we know it today. There was something about Elsa’s way of creating fashion that resembled the communication established by the Dadaists and Surrealist artists. Although Daniel Roseberry took over the creative direction of the company in 2019, the spirit of the original brand, and the iconic surreal seal, did not stop being present on the Roseberry’s catwalks. Each of his shows was an experimental journey through the realm of fashion and through history. With her designs and Roseberry’s constant revival of the icon that she was, Elsa stays in the spotlight of todays fashion. We’re sure not many of you know the full history behind this extraordinary woman, so we took our time to present a little bit of her life, most memorable designs and what shaped her to be one of the most innovative designers of her time.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

Early Life

Elsa Luisa Maria Schiaparelli was born on September 10th, 1980 in the Corsini Palace in Rome as the younger daughter of a highly intellectual but also conservative Catholic family. Uninterested in progressing in school, but extremely intelligent and curious, she becomes a constant assistant to uncle Giovanni, the famous astronomer, in his hours-long study of the stars and the universe. At the age of 19, she enrolled in philosophy at the University of Rome, and two years later, inspired by mysticism, she published a collection of poems about love and suffering. Because of such an action, Elsa is condemned by her relatives, and the family sends her to a nunnery for enlightenment. However, as the hunger strike immediately begins, her parents are forced to return her from the monastery. But not for long.

A year later, Elsa accepts a job as a children’s governess and prepares to move to London. On her way to a brighter future, she stops in Paris, which delights her both with its style and avant-garde tendencies from the beginning of the century. Then she gets the opportunity to enjoy the ball for the first time, so in the absence of an evening toilet, Elsa buys a long, dark blue cloth that she wraps around her body like a drapery, hanging it above her chest with a single needle. Her unconventional style becomes recognizable from the very beginning, and every move in styling her own and her close friends’ clothes reveals Elsa’s avant-garde spirit. Nevertheless, this unusual Italian continues her journey and spends all her free time in London visiting operas, visiting museums and listening to lectures. And it was at one of the numerous lectures on magic, eternal life and the power of the soul that she fell in love with the Polish lecturer Wilhelm Wendt de Kerlor, whom she married a year later. In 1921, the young married couple left for New York, where Wilhelm continued his successful career.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

On the other hand, Elsa is impressed by the modernity of the city, but also by American women who play tennis and golf, drive cars and wear clothes without corsets. Unfortunately, shortly after the move, their marriage is marred by a crisis and Wilhelm leaves Elsa right after she gives birth to their first and only child – daughter Maria Luisa Yvonne Radha better known as Gogo. At that moment, on the verge of poverty, jobless and completely alone, Elsa begins her struggle for a different life. By chance, she met Gaby Picabia (the ex-wife of artist Francis Picabia), who was trying to establish a small clothing store designed and produced in Paris and in New York. That’s how Elsa started working for Gaby, and thanks to her good connections and acquaintance with the artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, she secured them a permanent clientele. Given that New York became a refuge for many artists and writers during the war years, in response to the general disorder in the world, and yet in parallel with the avant-garde movements that were born in Europe and the strengthening of dadaism in Zurich, a series of anti-artistic movements permeated every area of ??creative work in the following period.

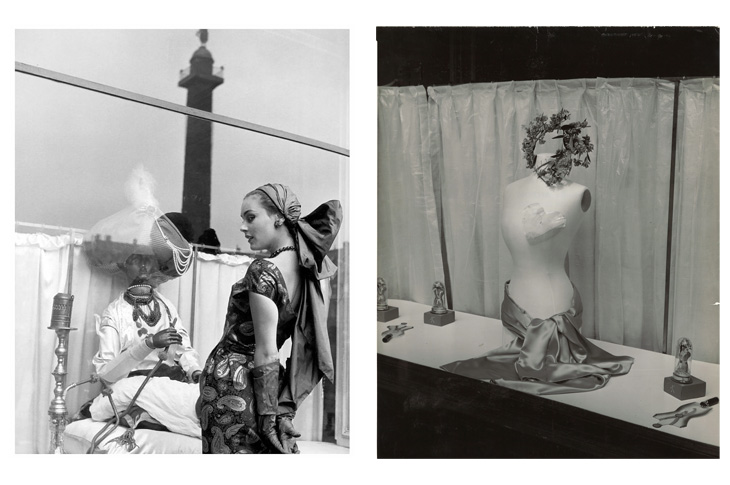

Right: Shocking Window Display

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

Creating Schiaparelli

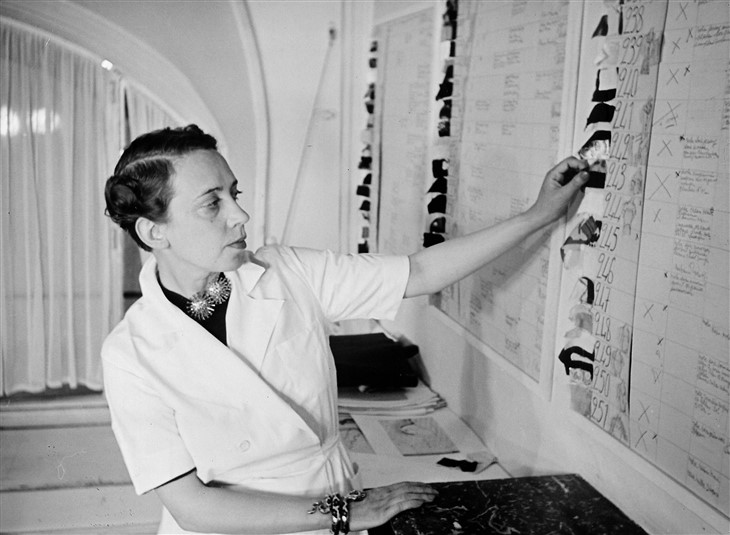

The first thing Elsa made was a black knitted sweater with a white bow around the neck that produced the optical effect of being a butterfly. The sweater was worn by a well-known Hollywood screenwriter, Anita Loos (author of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes), which led Strauss stores to order forty more units. However, she did not seriously consider the fashion business as a means of earning a living until 1922, where she attended a Paul Poiret parade as the companion of an American millionairess; the French couturier, who would eventually become one of her best friends, and the one who really encouraged her to unleash her creativity. Thus, in 1927 Schiaparelli opened his first store on Rue de la Paix, whose door bore the emblem “Pour le sport” (‘For sport’), as she wanted to dress women in the style she had known during her stay in America. The collection included swimwear, linen dresses and a ski suit. Appearing in a split skirt, the forerunner of shorts, which was shocking for that era, tennis player Lili de Alavez surprised the tennis world, wearing it in 1931 at Wimbledon. Two years later Elsa presented her first complete collection, a precursor to prêt-a-porter, a concept that was not yet known. But, despite her initial intention, the final accolade came with her first evening dress, a long model that was combined with a tails jacket, which was copied throughout the world and marked her entry into the high sewing. In 1935 she opened her own fashion salon on the Place Vendôme, opposite the Ritz Hotel, with a new slogan “Bon vêtements de travail!” (‘Quality work clothes!’), although, paradoxically, the Italian stylist has gone down in fashion history for her extravagances and eccentricities.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

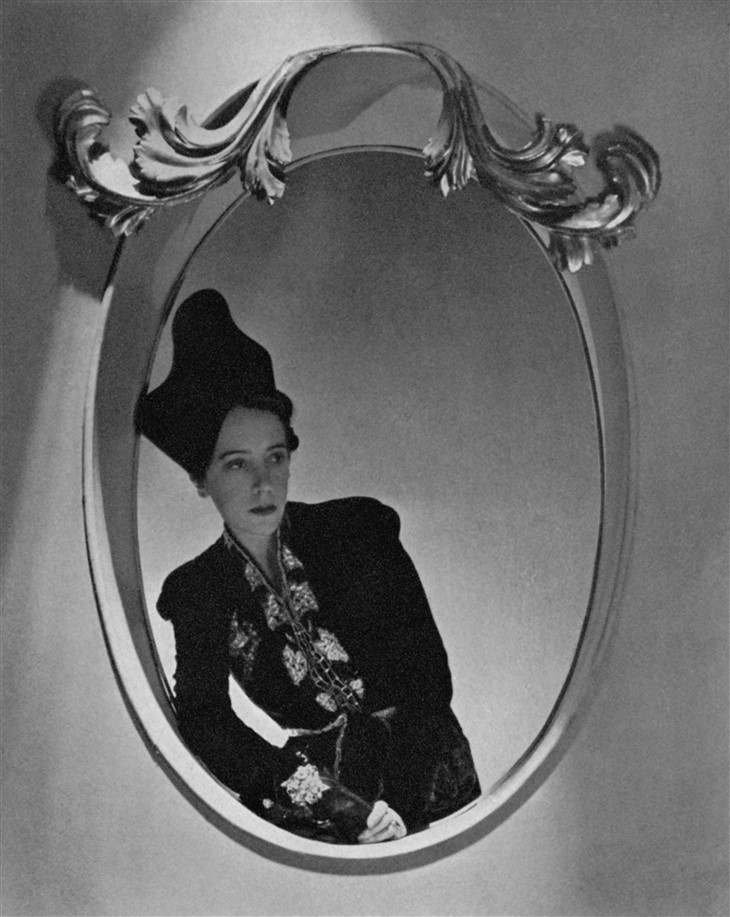

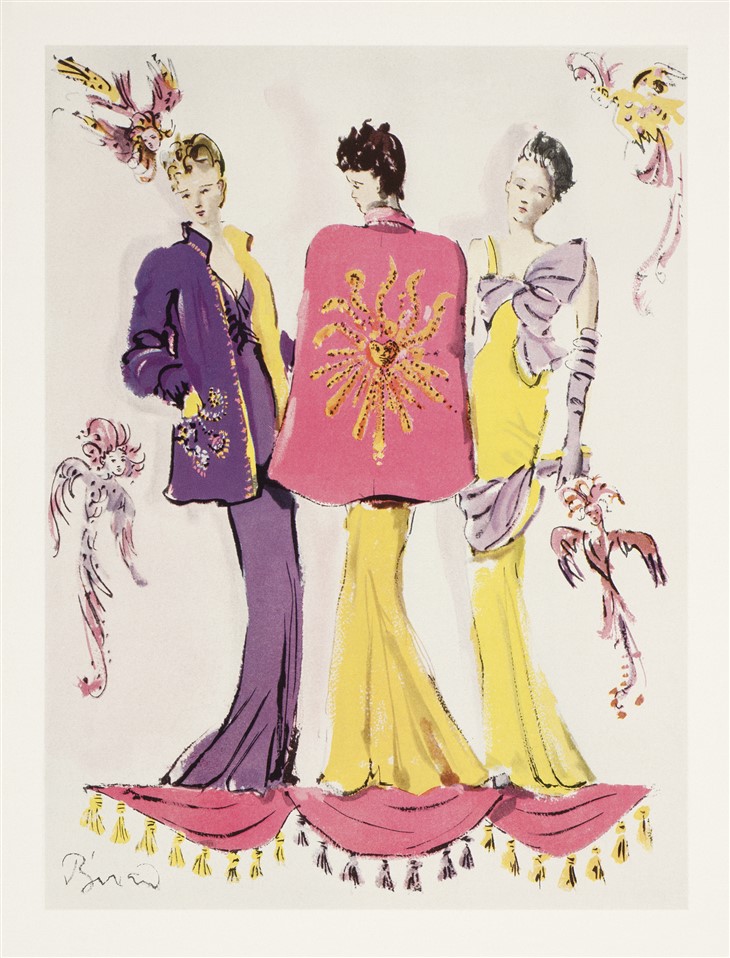

Until the outbreak of World War II, the Italian lived her most splendid life. There were many women who abandoned other fashion greats, such as Jean Patou or Coco Chanel, and started wearing Schiaparelli. Her followers were numerous. She especially liked to surprise her clients with surprising, refined and extravagant designs. Her ideas, along with those she took from famous artists, were embodied with considerable skill by masters such as Dalí, Christian Bérard, Van Dongen, and Jean Cocteau, whom she hired to design fabrics and accessories for her and who designed Maison’s most recognizable piece of jewelry – the eye brooch. The great jeweler Jean Schlumberger made jewelry and buttons for her, and the photographers Cecil Beaton and Man Ray were in charge of capturing the images of her designs.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

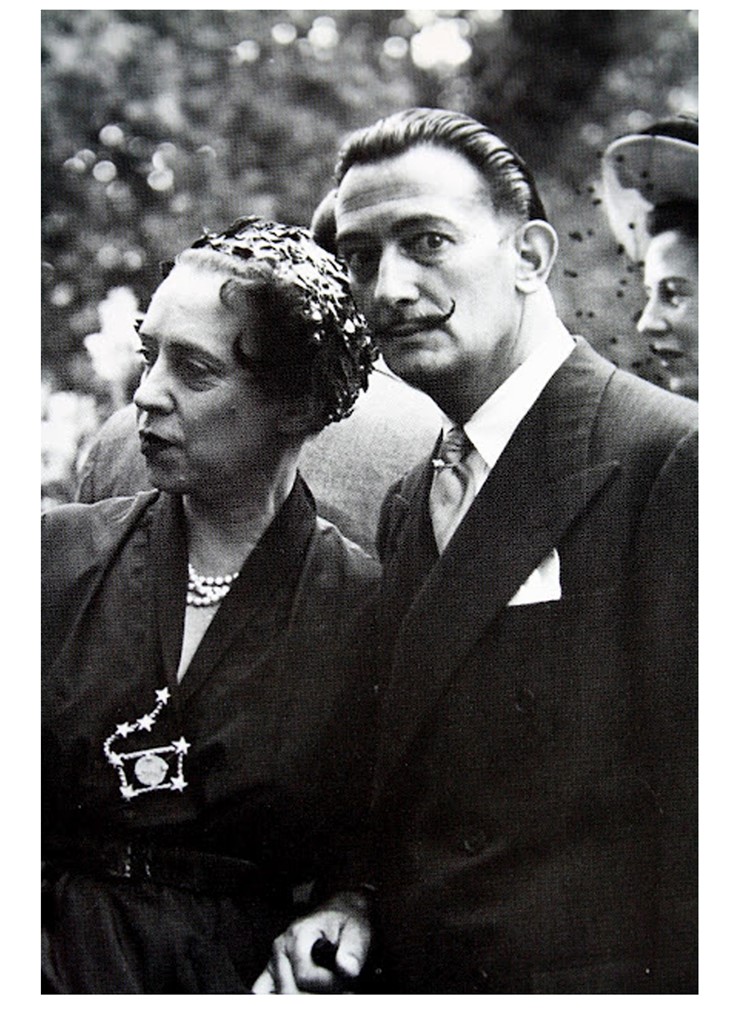

It is impossible to talk about the Schiaparelli fashion house and not mention the main source where Elsa Schiaparelli got inspiration for her creations – Salvador Dalí. Inspiration, perhaps, is not a good enough term for what was actually the case. Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dalí’s relationship was more of a complementary relationship and the creation of a new world that brought together fashion and art in a way that had not been seen before. The designer and the artist began working together in 1934, a time that was particularly volatile in Paris. However, this was precisely the time when their wealthy clients were interested in exploring the most daring solutions. Their innovative spirit came to life in a display of dresses, fashion accessories, jewellery, homewares, drawings, paintings and photographs, which reveal their direct relationship to design. Their joint creations revolutionized the way clothes are made and changed the course of the fashion world forever. The unmistakable spirit of the two visionaries remains present in Schiaparelli pieces to this day.

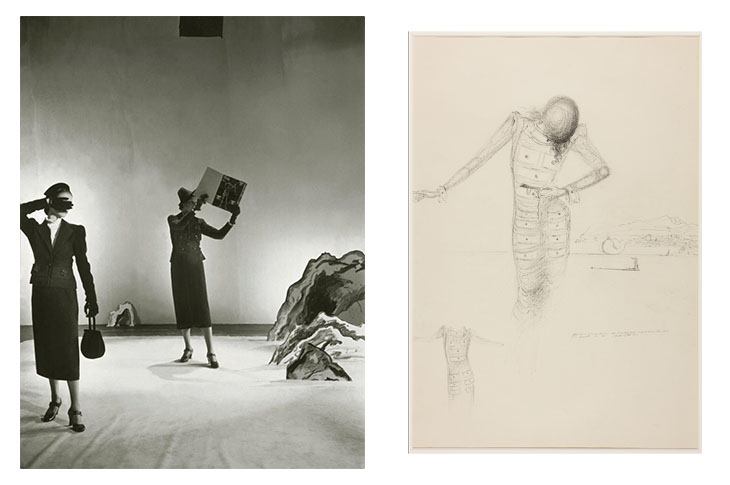

Right: Schiaparelli suit with drawer pockets designed by Dali for Schiaparelli © Salvador Dalí ADAGP

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

One of the most iconic designs these two made is the famous hat-shoe. In 1933 Dali painted his wife with one of her shoes on his head, in order to sketch a shoe-shaped hat for Schiaparelli in 1937. The cap has the shape of a woman’s high-heeled shoe and was published in the autumn-winter collection of 1937-38. Apart from Schiaparelli herself, it was also worn by Gala Dali (Salvador Dali’s wife) and Daisy Flowers, one of Schiaparelli’s best clients. Following is the Cabinet dress, which was a part of 1936 collection inspired by the concept of drawers, who was later immortalized by legendary Cecil Beaton in a series of photographs for Vogue. In 1938, they teamed up again for the Skeleton dress, which made her return to Roseberry’s Haute Couture SS22 Collection. The Skeleton dress was made beyond all the conventional standards of time, it featured 3D bones rendered internally by hand embroidered pads onto the rayon crepe. A part of Schiaparelli’s Le Cirque parade collection, the dress introduces one of the most surrealist works of the time. Also worth mentioning are the lobster dress and tears dress. The Lobster dress is a simple white evening dress with a lobster motif painted by Dali, who used to incorporate them into his products. His painting for Schiaparelli was transferred to fabric by Sache, a leading silk designer. The Tears dress is a white evening dress that has a thigh-length veil and motifs that give the illusion of torn animal flesh. The tears are meant to represent fur, and the dress itself is made of animal fur turned inside out.

© Le Printemps Nécrophilique, Salvador Dalí, akg-images © Salvador Dalí, Fundacio Gala-Salvador Dalí / Adagp, Paris 2016

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

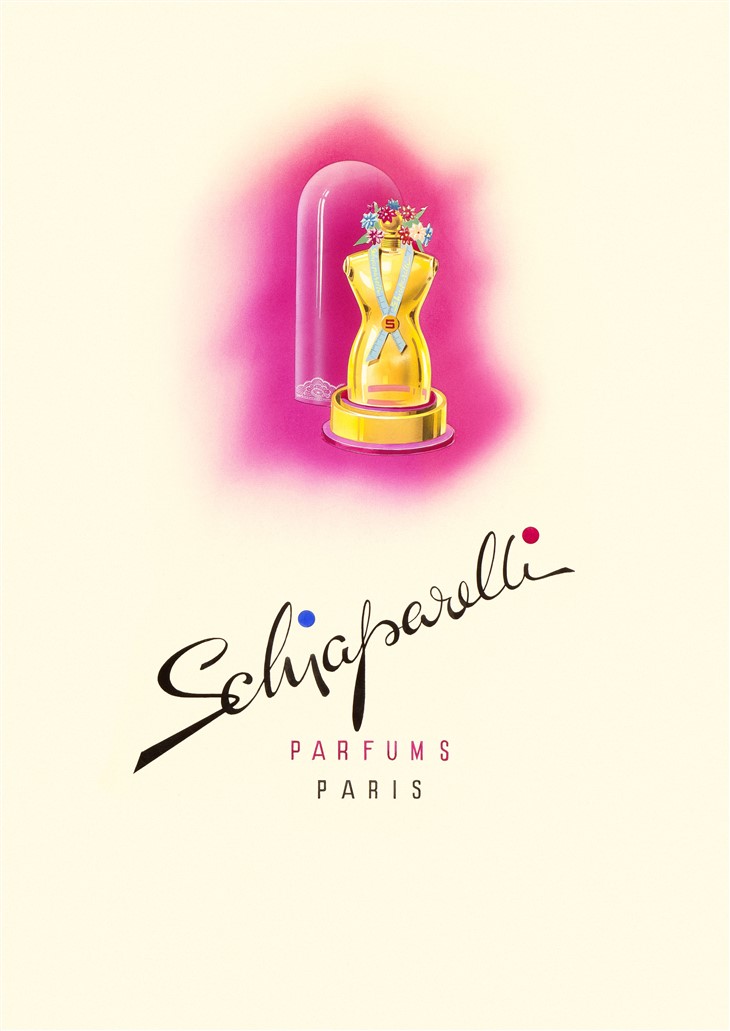

Also, she was involved in perfume business. In 1928 she launched S, which did not achieve the expected success, and then, in 1933, Schiap, Salut et Soucis. The period from 1936 to 1938 was certainly the most creative for the designer. She first launched Shocking, with a strange bottle of surrealist inspiration, which represented a mannequin with shapes like Mae West, one of his best clients. Her next perfume, Sleeping, was shaped like a candlestick with a candle on top and the red stopper resembled the flame. Following the success of the perfume line, Elsa yet again collaborated with Salvador Dali for Le Roy Soleil, created in 1947 as a tribute to Louis XIV. The bottle was made by the illustrious crystal-maker Baccarat, presented in a large gilded metal conch. It features birds in flight illustrated on the sun which contribute to trompe-l’oeil face.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

Schiaparelli also made the gloves that incorporated gold nails, or the evening dress made of rags, which could be considered a precursor to the current punk style, included lip-shaped pockets in the skirts and played a decisive role in the designs of hats without being neither a seamstress nor a dressmaker (in fact, the small red felt model adorned with rooster feathers became one of the hallmarks of her house); apart from those already mentioned in the shape of a shoe or a telephone, two of her most famous hat models were in the shape of an ice cream cone and a lamb chop. In 1933 she introduced the wide-shouldered pagoda sleeve that determined fashion lines until after World War II; her evening suits were made of tweed or burlap fabrics, she dyed the skins in bright colors, put padlocks as closures on the suits, and incorporated plastic zippers into the dresses, allowing them to be seen, as another decorative element, instead of hiding them, which was the politics then.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

She presented in her collections phosphorescent brooches in the form of insects and aspirin necklaces; she thought buttons were boring, so she turned them into paperweights, sugar cubes and small sculptures, as in his 1938 collection, “Circus,” in which the buttons on her suits were jumping acrobats or merry-go-rounds. The French company Colcombet created for her a printed newspaper fabric from which, in full Picassoian inspiration, she made handkerchiefs for her neck. Schiaparelli embroidered the signs of the zodiac on her clothes and sold bags that light up or play a tune when opened, or have a clock on the closure. Her provocative and irreverent elegance was a complete success, as she offered women an alternative that extended the dress to the point of art. Yet despite these gimmicky attention-grabbing devices, her designs were downright practical: trouser suits paired with open jackets that allowed for easy movement and boleros that protected the shoulders.

Courtesy of © Schiaparelli

Ninety per cent are afraid of being conspicuous and of what people will say. So they buy a grey suit. They should dare to be different. – Elsa Schiaparelli, Schocking Life

Lover of color that she was, she made one of Bérard’s pink shades her own, a color later baptized by her friend Paul Poiret as shocking pink (‘surprising pink’), and enthusiastically promoted it in scarves, lipsticks or evening wear. In fact, she liked this adjective (shocking) so much that she used it for everything in his life: her last collection, presented in 1952, was called Shocking Elegance, and when her biography appeared two years later it was titled: Shocking Life.

During World War II Schiaparelli went to the United States and in 1949 she opened a store in New York. She then settled in Hollywood (it must be said that, of all the fashion designers, she was the most successful in the film world), where she designed the costumes for authentic sex bombs like Zsa Zsa Gabor or Mae West, Joan Crawford, Katharine Hepburn. Despite these triumphs, and the many lectures she gave, Schiaparelli did not manage to establish herself completely in America. She did not return to France until 1945, but, as her friend Poiret, her originality had no place in a world plagued by post-war economic problems. She presented her last fashion show in 1954. Until her death in 1973, she lived on the income from her perfume sales.

Today, thanks to the chairman of the Tod’s Group Diego Della Valle, who purchased the perfume company and the rights to the brand, the Schiaparelli house continues to exist and bring out designs inspired by the genius herself. Guided by the creative director Daniel Roseberry, the house is rising fast to the one of the most popular and buzz-worthy brands.

Words by DSCENE Digital Editor Maja Vuckovic.