For its third edition, the Biennale für Freiburg returns under the title HAPPY PLACE, transforming the city into a constellation of critical encounters with leisure, desire, and displacement. Curated by Lorena Juan, the 2025 edition brings together 37 artists and collectives whose works intervene directly in Freiburg’s public and cultural spaces, uncovering the social and political forces that shape how happiness is imagined, sold, and consumed. From a reimagined souvenir shop to installations suspended in a historic cable car, HAPPY PLACE questions who gets to feel at ease, and at what cost.

ART

In this interview for DSCENE Magazine, writer Bettina Wagner speaks with Lorena Juan about the contradictions at the core of tourism, the curatorial strategies behind this year’s edition, and how art can both comfort and confront within the same breath.

This year’s Biennale is titled HAPPY PLACE. What was the initial spark or personal experience that led you to this theme? – The initial spark came from reflecting on how the idea of “happiness” is constructed and sold to us—particularly in travel and tourism. Inspired by Lauren Berlant’s concept of “cruel optimism,” I wanted to explore how the promise of the “happy place” often conceals the very forces—exploitation, environmental harm, social inequalities—that it claims to escape. Freiburg itself, with its reputation as a green, livable, “happy” city, became a perfect mirror for this. I wanted to exaggerate this image, to ask: what does it mean to frame a city or region as a “happy place” when the world right now is anything but? This tension and these contradictions are where the project began.

In your curatorial statement, you explore the tension between comfort and conflict. How does the Biennale negotiate that tension in its artistic contributions? – Many of the artworks dive into this tension by inhabiting the idea of “the happy place” and then destabilizing it. I’m interested in narratives that invite reflection and embrace ambivalence, so it was important for us to work with artists who understand the seductive power of these fantasies—and how they’re often built on extractive systems, whether that’s labor, landscape, or culture.

For example, the photographic series Postales para desaparecer (Postcards for Disappearing) by Esvin Alarcón Lam explores how the tourism industry can be used as a tool of erasure. These images, captured in Guatemala City, document how the Guatemalan National Institute of Tourism placed glossy promotional posters over activist materials that demanded justice for the genocide of Indigenous populations. The tension is palpable: the very images meant to entice visitors to an idyllic “happy place” simultaneously function to erase historical memory and silence dissent. In these photographs, we see comfort and conflict layered together—escapism and violence held in uneasy balance.

At the same time, the Biennale’s humor and playfulness—like in the “1 ☆ Review Tour” by !Mediengruppe Bitnik—allow for moments of absurdity. This performative guided tour humorously exaggerates poorly reviewed sites in Freiburg, prompting reflection on how such systems shape our experience of the city. We wanted to create spaces where people could feel at ease enough to face discomfort, and where conflicting emotions could coexist. That, for me, is where the real power of art lies: in revealing that comfort and conflict are not opposites, but deeply intertwined.

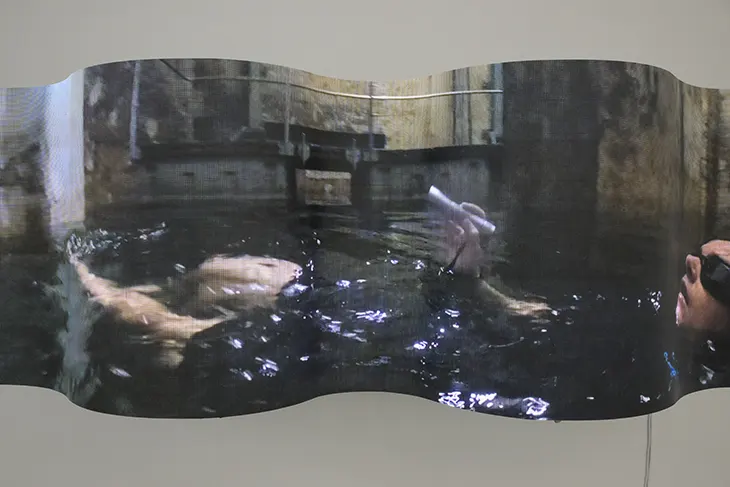

Can you share a few key highlights of the program—artists or works that you feel embody the spirit of HAPPY PLACE particularly well? – Absolutely. Two projects that come to mind immediately are Irene de Andrés’ Prora. A complex destination and Eve Tagny’s Underlying Spirits.

Irene de Andrés’ Prora. A complex destination is a documentary that traces the evolving life of the Prora complex on Germany’s Baltic coast. Originally conceived as a massive seaside resort for Nazi leisure propaganda, Prora’s history is a mirror of shifting political and economic agendas—from ideological tool to military barracks to luxury destination. What I find so powerful about Irene’s work is how it shows leisure itself as a battleground of narratives. She reveals how the very spaces we associate with comfort and escape are often built on the repurposing—if not outright erasure—of conflict-laden pasts. Prora’s transformation from totalitarian project to capitalist playground exposes how “happy places” can be engineered and re-engineered, shaped by power at every turn.

Another highlight is Eve Tagny’s Underlying Spirits, a participatory installation that invites visitors to physically engage with the histories beneath their feet. The work layers photographs of landscapes and botanical specimens—some from Germany’s Oberrhein region, others from the UK and Cameroon—while referencing the museological practices that have long framed colonial legacies as objects of curiosity. Visitors are invited to pick up and carry away images, activating an intimate, embodied relationship with the colonial entanglements of landscape and tourism. For me, Eve’s work speaks to the heart of the Biennale’s spirit: it unearths the shadows behind our longing for beauty and leisure, and reclaims agency in the process.

Both projects show how landscapes—whether an expansive beach resort or a carefully tended garden—hold the weight of history, economy, and desire all at once. This is very much the spirit of HAPPY PLACE: to open up these layered narratives and ask how we might reimagine our relationships to the places we visit and inhabit.

Site-specificity has always been central to the Biennale für Freiburg. How did the urban landscape of Freiburg shape this year’s artistic interventions? – Site-specificity has always been central to the Biennale für Freiburg. This year, the city’s urban landscape became a vital stage where the contradictions of tourism were made tangible. We focused on intervening in major sightseeing spots, transforming familiar places into sites of critical reflection.

One key example is the Schauinslandbahn, one of Germany’s oldest and longest cable cars. Patricia Domínguez’s work takes advantage of this iconic local mode of leisure, inviting visitors to consider how landscapes and scenery are constructed within national narratives—and how these narratives connect to faraway ecologies and histories. As people float above the fir trees on their way up to the Black Forest hills, they are prompted to think beyond the picturesque surface.

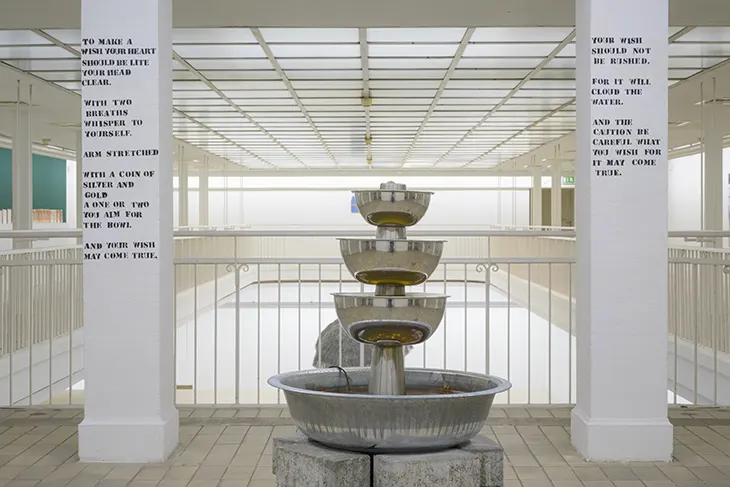

Another striking intervention is Irene Fernández Arcas’s Mediterranean chiringuito—a beach bar installed on the grass area of an indoor swimming pool. This playful space offers discovery, recovery, and joy, while simultaneously revealing the climate vulnerabilities and labor inequalities that underpin such idyllic images. This tension between enjoyment and critical reflection runs throughout the entire Biennale, encouraging visitors to experience Freiburg—and tourism itself—with fresh, questioning eyes.

At its core, HAPPY PLACE asks who benefits from the promise of happiness, and at what cost.

What challenges did you encounter when working with the city’s public or semi-public spaces, and how did artists respond to these constraints? – We faced logistical challenges, of course—permits, access issues, or simply negotiating the expectations of different actors involved who may not be familiar with contemporary art. But these “frictions” also became creative prompts. Artists responded by turning these sites into living spaces of negotiation.

For example, Elisa Duca’s Tentacle Memories directly engages with one of Freiburg’s most iconic and heavily visited souvenir shops at Münsterplatz. Rather than working around these constraints, she intervened right within the tourist economy by creating a series of postcards, keychains, and Christmas decorations that reimagine the usual souvenir imagery. These objects—populated by strange non-human agents—ask what kinds of stories souvenirs tell, and what versions of the world they reinforce. It’s a playful yet pointed way to highlight how even the smallest tokens of travel can become sites of power and myth-making.

To what extent do you see HAPPY PLACE as a political statement? – It’s deeply political. At its core, HAPPY PLACE asks who benefits from the promise of happiness, and at what cost. By framing tourism not just as leisure but as a system of power, the Biennale turns the search for a “happy place” into a lens for examining global inequalities and environmental injustices. Many works highlight the need to shift from consumption to care—an inherently political act.

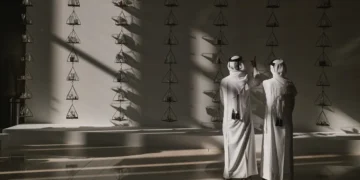

You’re working with both international and local artists. How important was it for you to create dialogues between different geographies or contexts? – It was essential. This Biennale asks us to look beyond local experiences and see how travel connects seemingly distant worlds. By bringing together artists from the Global South and local voices in Freiburg, we created a dialogue that challenges both romanticized visions of “elsewhere” and the idea that Freiburg is untouched by these dynamics.

For me, this approach also helps visitors see the city and the landscapes around them in new ways—inviting them to rethink their own roles as travelers, hosts, and inhabitants.

This is your first time curating the Biennale für Freiburg. How did you approach this role, and what did you want to do differently from previous editions? – I wanted to work at the Biennale für Freiburg precisely because my predecessors did such an amazing job creating an art project that was deeply attuned to the city and its surrounding landscapes, while also engaging with global conversations. For this edition, I wanted to build on that foundation by focusing on tourism, mobility, and how places are constructed and consumed—whether through Instagram shots, souvenirs, or urban development.

We wanted to create spaces where people could feel at ease enough to face discomfort, and where conflicting emotions could coexist.

What do you hope Freiburg residents or visitors will take away from their experience of HAPPY PLACE? – Ultimately, I’d like people to feel both invited and challenged: to enjoy the humor and playfulness in many of the works, but also to grapple with the deeper questions about how we move through the world, how we consume places and cultures, and how we might imagine more equitable and caring forms of travel and connection with other places.

My hope is that people leave the Biennale thinking not only about faraway holiday destinations, but also about their own city as a site of tourism, longing, and transformation. By encountering artworks that span local interventions and global connections, visitors might see familiar places with fresh eyes and rethink their own relationships to travel and landscape.

And finally, when you’re not curating, where is your personal happy place—whether that’s a specific location, or maybe a country you love to travel to? – I like enjoying small, fleeting moments that make me wonder at the beauty of things—like finding flowers growing between pavement stones, discovering a hidden path in a city I thought I knew, or simply laughing with friends.

Biennale für Freiburg 3 – HAPPY PLACE is on view from June 5 to July 27, 2025.

absolutely love this one!