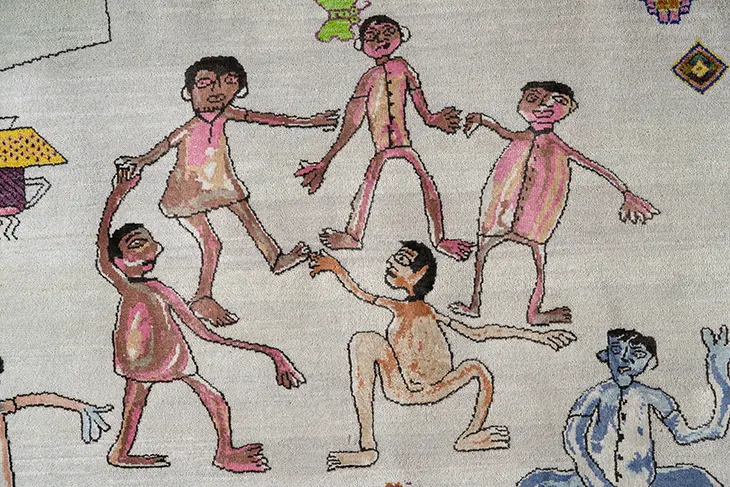

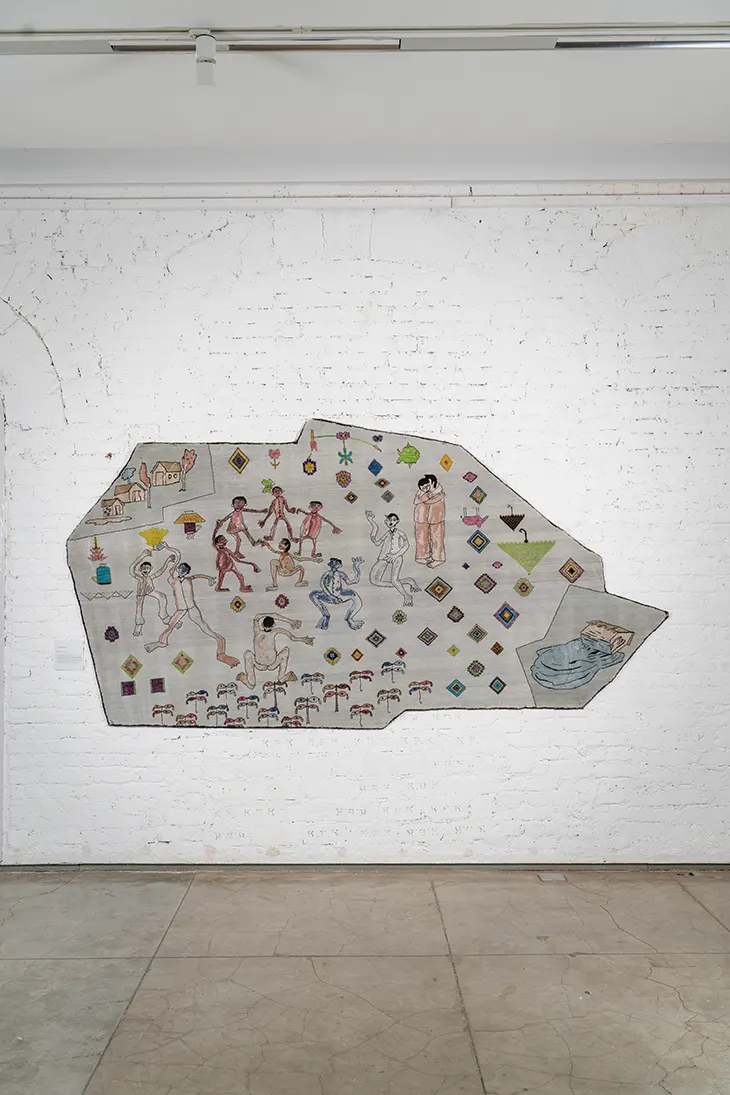

In his collaboration with Jaipur Rugs, artist Gurjeet Singh enters a space where craft, community, and storytelling intersect, quietly but powerfully. The collection, titled Dreamers, consists of 15 hand-knotted wall pieces that carry the weight of personal histories and unspoken truths. Created during a residency in rural Rajasthan, where Singh lived and worked alongside the artisans of Jaipur Rugs, these works draw from shared conversations, daily rituals, and the delicate emotional fabric of life under constraint.

INTERVIEWS

Known for his textile-based soft sculptures, Singh shifts mediums without losing the emotional core of his practice. In Dreamers, he responds to what he describes as “silent dreams and quiet resistance,” translating these tensions into form through upcycled saris and salvaged materials. The result moves between disciplines, driven by emotion, shaped by dialogue, and anchored in the lived experience of the women and men who wove them.

DSCENE Editor Katarina Doric spoke with Singh about vulnerability, authorship, and the realities that often remain hidden beneath the surface.

How did your time spent with the artisans in rural Rajasthan shape your approach to the Dreamers collection? – Spending time with the artisans in Jaipur was deeply transformative. It wasn’t just about observing craft, it was about being invited into their lives. Through long conversations, shared meals and quiet, intimate moments, I came to understand the emotional layers and lived realities that often go unspoken. What stood out to me was the complex intersections of gender, class and culture – how these forces inform not only their creative practices but their sense of self. I also noticed a strong sense of yearning for freedom, ambition and self-expression. These emotions became the heart of the Dreamers collection and they formed the foundation of this show.

You often work with soft sculpture and discarded textiles. What was it like to translate your visual language into hand-knotted rugs for the first time? – While this was my first time working with hand-knotted rugs, textile art itself isn’t new to me. In so many ways, it felt like an extension of my existing practice. Collaborating with the artisans was an incredibly enriching experience, full of learning. Seeing my visual language come to life through this centuries-old craft was deeply satisfying.

While the material form was different, the emotional core, which is my approach to storytelling, remained very much the same. The works have been made with repurposed old silk saris, which were then cut into vertical panels and woven together to create these rugs. Similarly, the soft sculptures have also been created using upcycled fabric salvaged from damaged old rugs that were burnt in an accidental fire.

Spending time with the artisans in Jaipur was deeply transformative. It wasn’t just about observing craft, it was about being invited into their lives

You’ve described seeing “silent dreams and quiet resistance” in the lives of the artisans. Could you share a specific moment or conversation that stayed with you during the residency? – There were many quiet, powerful moments that stayed with me, but my interaction with Boogli and her mother left a strong impression on me. From the patriarchal structure in their household, to their submissive postures and veiled faces, it revealed how their lives are shaped by duty, not desire.

One moment that made a lasting impression on me was when Boogli’s mother asked if she’d ever like to travel, she simply said, “Kaun jaane dega?” (Who would allow me?) That one sentence captured a lifetime of limitation and inhibition. For women like her, even dreaming feels out of reach. This body of work becomes a way to honour those silences, to give form to stories that might otherwise go unheard.

Each rug in Dreamers carries a distinct emotional register. How did you decide which stories or inner states to translate into visual form? – For me, art begins with emotion, often intense and difficult emotions. Listening to the stories of others, especially when they’re layered with pain, injustice or quiet resignation, can be deeply unsettling. There were many moments during the residency when I felt emotionally overwhelmed, when I had no solutions to offer, no way to change the circumstances I was hearing about. That helplessness, that brokenness, stayed with me.

It led me to question everything: Why are things this way? How did we get here? And when there are no clear answers, the only way I know how to process those questions is to express myself through my art. The visual forms became a way to hold those feelings, to give shape to the silence and the sorrow.

The process naturally turned into a conversation; it became about co-creating with the artisans and using this collection as a platform to centre their voices.

Black Sun stands out for its political and emotional intensity. How did current events inform its creation, and what kind of response do you hope it provokes? – Black Sun serves as a stark metaphor, while the sun often symbolises light and hope, here it emits only darkness. It asks a deeper, lingering question: When will we see the light? When will we find our way home? When will we be free to dream?

The work was shaped by the emotional weight of my visit to Jaipur’s prison, where the atmosphere was one of silent despair. That heaviness was further intensified by the Indian Supreme Court’s rejection of same-sex marriage. Through this work, I hope people are reminded of the quiet power.

The Portraits of Boogli and Her Mother is a deeply intimate work. What role does personal storytelling play in your process? – Personal storytelling is at the heart of my practice. When I met Boogli and her mother, Godi, there were pictures of all the artisans at Jaipur Rugs’ office, except Godi’s. When I met both Boogli and Godi, there was a quiet intensity to the meeting; unspoken tensions, emotions and intergenerational dynamics that lingered just beneath the surface. I could feel the weight of everything that wasn’t said. As with all the pieces in Dreamers, this work is rooted in an emotion I experienced during that interaction. Each rug carries a personal story and each emotion becomes the thread through which those stories are told.

For women like her, even dreaming feels out of reach. This body of work becomes a way to honour those silences, to give form to stories that might otherwise go unheard.

How did you approach collaboration with the artisans in a way that honoured their authorship while still realising your artistic vision? – When I was invited by Jaipur Rugs for the residency, I came in with an open mind. I wanted to understand the craft, not just the technique, but the history and culture behind it, and see how it might speak to my own practice. As I spent time with the artisans, I began to notice how many of the themes I explore in my work, like identity, freedom and the courage to dream, were present in their lives too. The process naturally turned into a conversation; it became about co-creating with the artisans and using this collection as a platform to centre their voices and stories.

Did working in a slower, more repetitive medium like rug weaving shift your perspective on time, labour, or art-making? – Absolutely. I found great joy in the slowness of the process. There’s something grounding about working with a medium that unfolds over time; it demands patience. It reminded me that ideas don’t need to be rushed; they deserve space to breathe and evolve. The slow-paced process also allowed the artisans the time to reflect and refine their decisions when it came to making creative choices around colour and design.

What kinds of reflections or discussions do you hope Dreamers will spark among those encountering these works for the first time? – Dreamers invites viewers to reflect on the universal longing to be seen, heard and free to define one’s own identity. Beyond the craftsmanship, I hope people recognise the unacknowledged reality, the resilience, and the deep humanity of the artisans. It’s a call to honour not just their art, but their stories and to question the structures that so often silence them.

I’m dreaming of freedom without fear, in my art but also in how I exist in the world.

If you had to describe the collection in one word that doesn’t exist in English, which word would it be, and why? – If I had to choose one, it would be Azadi, a word from Hindi and Urdu that means freedom. It’s not just about political or physical freedom, it’s about the freedom to choose, to express, to dream on your own terms.

What are you dreaming of next—artistically, politically, or personally? – I’m dreaming of freedom without fear, in my art but also in how I exist in the world. A freedom that isn’t conditional or compromised in any way. That, to me, is the ultimate dream.