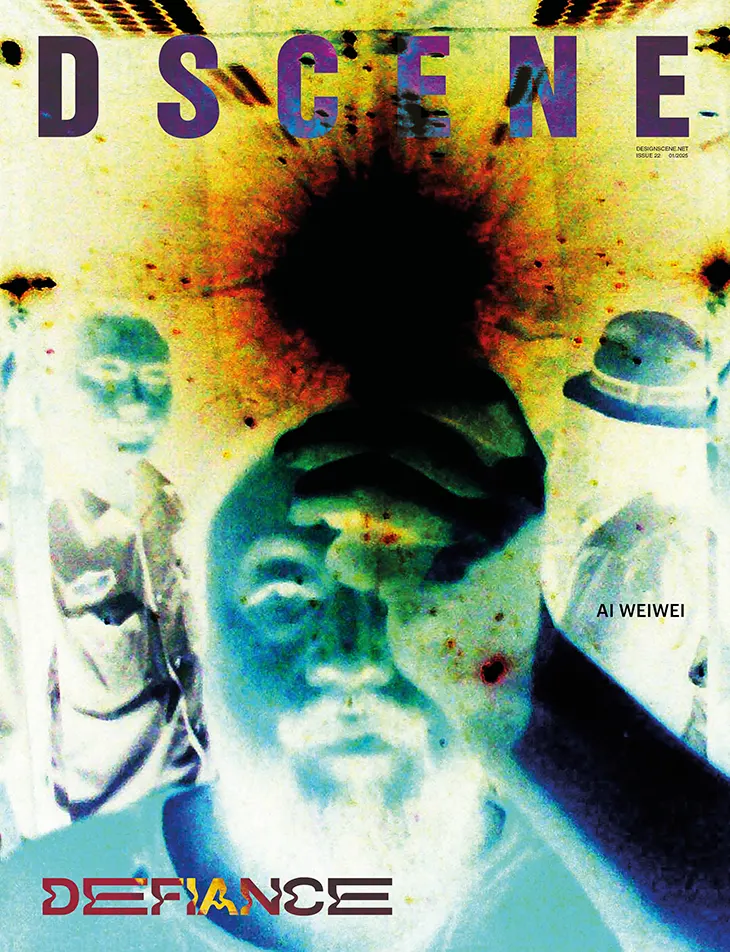

Maurizio Cattelan has spent the last three decades staging interventions that defy easy interpretation, at once absurd and exacting, comic and cutting, his work hovers in the uneasy space between reverence and ridicule. From a taxidermied horse crashing through gallery walls to a banana duct-taped to a fair booth, Cattelan has long been dismantling the rules of institutional art with acts that appear casual but leave deep cultural imprints. His visual language is rooted in contradiction: grief and slapstick, critique and complicity, spectacle and silence. Few artists have challenged the moral weight of museums with as much elegance, or audacity.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

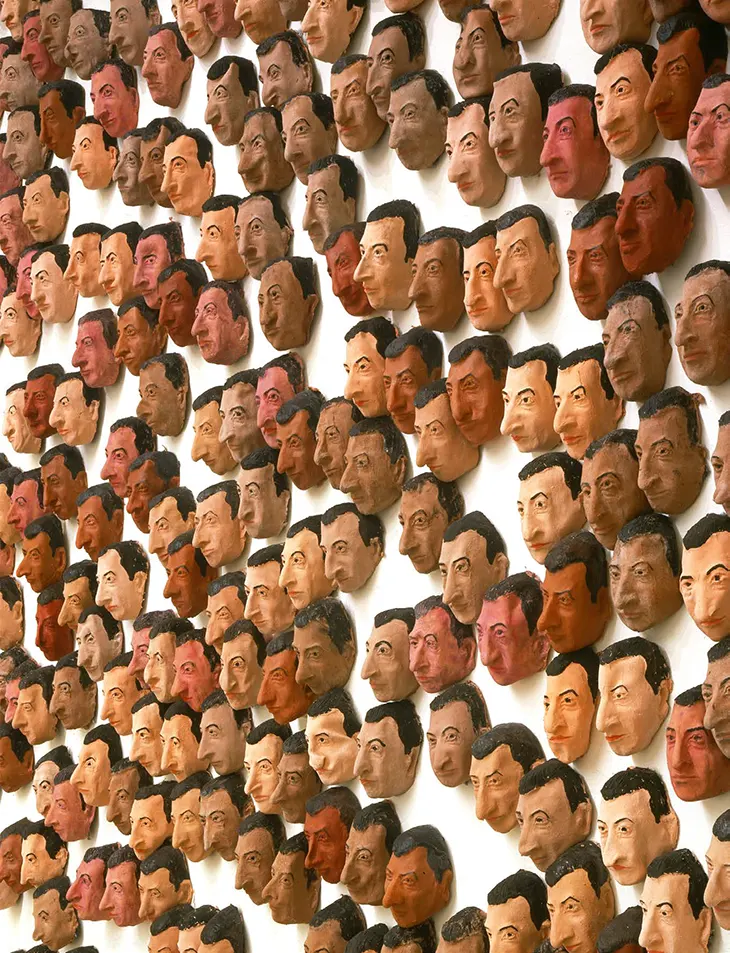

His latest project, Endless Sunday, takes over the entire Centre Pompidou-Metz as both a retrospective gesture and an act of rebellion. To mark the museum’s 15th anniversary, Cattelan inserted nearly 40 of his own works into the space while simultaneously reconfiguring the institution from within, curating over 400 pieces from the Pompidou’s collection into a looping, alphabetized trail that transforms the museum into a labyrinth of memory, power, and suspended time. Working closely with director Chiara Parisi and incorporating texts written with inmates from the Giudecca Women’s Prison, Cattelan repositions the museum as a site of friction, fantasy, and fractured authority. In this conversation with DSCENE Editor Katarina Doric, he speaks about architecture as metaphor, the theater of art, and the strange melancholy of Sundays that never end.

What does an “Endless Sunday” look like in your mind? What made it the right title for this collaboration with the Centre Pompidou? – Dimanche is an ambiguous moment, somewhere between pleasure and idleness and anxiety and trepidation for the week that begins again. It interests me precisely because of its double face, its being the end and the beginning together. An Endless Sunday is a limbo of inactivity to be experienced at once as condemnation and as absolution.

Every Sunday gives us a second chance, or at least the illusion that there is one.

You’ve said before that humor is a form of truth-telling. What kind of truth were you after when you started shaping this exhibition? – If in the course of my career I had found answers, not to tell the truth, I would have stopped working… The research is not yet finished, but I found many interesting questions in organizing together with the other curators.

The exhibition reads like a labyrinth of time, emotion, and contradiction. What was the first thread you pulled when building this circular trail through the museum? – It was like moving through the thickest woods: I tried not to be blinded by the great masterpieces, viewing them as dead-end streets, and instead kept following the pebbles, as if I were Le Petit Poucet, to get to the solution. Traversing a collection like this, that ranges from the early 20th century to the threshold of today, is like traversing unknown cities with only the compass of the eye.

The layout follows the alphabet, a format often used to teach children. Why did you choose something so structured for a show that feels inherently free? – Exactly because of the contrast: with Chiara, we wanted the exhibition to be open, usable from multiple points of view and different levels of reading, but to have our own indication of how it can be enjoyed. It’s like tasting a plate of cheeses: the waiter tells you in what order to taste them, but nothing to stop you, once the waiter has left the table, from starting with the tastiest.

How do you see the act of co-curating with a major institution’s collection – as disruption, homage, sabotage, or something else entirely? – We worked by detours, by sudden illuminations, by failed tests, and by missed meetings. As in certain choral novels, everyone writes a chapter without knowing exactly what the other will do, but in the end, the book exists. And it couldn’t be written any other way. And then, the abecedary invented for the exhibition became an open dictionary, where every visitor, every artist, every inmate who participates can rewrite meanings.

I have always thought that contradiction is a great starting point for getting to the bottom of things.

Inmates from the Giudecca prison contributed to the exhibition texts. What did their words show you that you hadn’t considered before? – They brought in something that cannot be simulated: the direct experience of surveillance, of suspended time, of guilt as a condition: an endless Sunday. Their voices served as a counterpoint to the institutional chorus, and I must say they did not contribute to the exhibition; they cracked it.

From a taped banana to a skeletal cat the size of a dinosaur, your work lives between comedy and collapse. Do you think museums are finally catching up to your tone? – I’m afraid the world is catching up to the tone, and it’s not good news!

You’ve created an experience that resists authority while being hosted by one of France’s most established institutions. Is contradiction part of the point? I have always thought that contradiction is a great starting point for getting to the bottom of things. It is the Schrödinger’s cat paradox: until we open the box, the cat is simultaneously both alive and dead, as the artist can be inside and outside the institution at the same time.

This show is as much about what we do with our time as it is about what art does with ours. What would you do if all your Sundays really were endless? – I would try with all my might to return to the reality of changing days, like the protagonist of Groundhog Day. I would struggle to live in a city where the seasons do not change, let alone the days of the week! Sunday is a day that is not well understood. It is a day that does not end because it does not want to choose what to be. Like certain works. Sunday makes me think of two opposite things that coexist: Totò in black and white, saying things that seem light and are instead fierce. And then that strange melancholy that comes when everything stops, but you don’t – you stay there, feeling time slipping by. We are not caught up in work, but neither are we really free. Every Sunday gives us a second chance, or at least the illusion that there is one. Dimanche sans fin is a Sunday that repeats itself, not out of nostalgia, but because each time it gives us – perhaps – a chance to change the ending.

You’ve always challenged the idea of what art is supposed to be. Has your definition changed at all while working so closely with other artists’ works here? – I don’t think there is a definition for art that can apply to everyone, not even for a second. The definition I can give myself today will not be the one I gave in the past, because my experiences are different, I remember or do not remember happenings and encounters. So yes, it has certainly changed, and it has been enriched with new nuances, because I have had the opportunity to learn from work that I did not know.

All my works, when looked at closely, reveal my obsessions.

The Breton Wall feels like a manifesto of curiosity and chaos. What object or image in this show do you think best mirrors your own obsessions? – All my works, when looked at closely, reveal my obsessions. Some works in the exhibition belong to my path that are like rediscovered, fallen into a moment of oblivion and now withdrawn from the drawer to complete the profiling of my identikit; this is also why it is so interesting to have Breton’s wall in the exhibition. Looking at Breton’s studio is like going inside his head: you have before your eyes a visual atlas of his interests, as if it were a Warburg album, or the desktop of my computer, to be more prosaic but made of physical objects. Each of these objects comes to life and speaks, telling its own story.

There’s a strong sense of theatricality throughout the exhibition. Is the museum just another kind of stage – or a place where the script collapses? – The museum is the theatre: a building with space for the audience and the stage. If a group exhibition is a stage, it is a place trodden only by co-starring actors; there are no solos.

Some viewers still get angry at your work. Do you think anger is a form of engagement, or just another kind of laziness? – I think anger is a form of care: you get angry about a cause you care about, a lack of rights, and injustice. Anger is a good thing, the opposite of laziness. Unless you’re getting angry on social networks, it’s a waste of time.

Ideas don’t come quietly – they are as loud as thunder and slap you in the morning even before you’ve had your coffee.

Now that you’ve staged an Endless Sunday, what comes after the weekend? Is there a new idea quietly forming in the background? – Ideas don’t come quietly – they are as loud as thunder and slap you in the morning even before you’ve had your coffee. I’m ready to turn my cheek to the next one.

One of the best Maurizio Cattelan interviews so far ❤️🫶