After days of sun-drenched afternoons at Milan Design Week, stepping off the plane in Bucharest felt like crossing into another world. It was April, but the air was sharp and cold, heavy with a kind of ghostliness. I had flown in for an art exhibition (nothing connected to Dracula, nothing gothic) and yet, maybe because of the sudden shift in atmosphere, the idea of visiting Bran Castle crept into my mind almost immediately.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

Less than twenty-four hours later, after a hurried, restless night in Bucharest, I found myself in a car headed north, driving toward the mountains through a landscape that grew increasingly monochrome. By the time I reached Bran, the snow was falling so heavily that for a moment I wondered if I would even make it back. Everything was white, the castle a jagged, improbable silhouette against the storm, a presence both defiant and inviting. It was the perfect setting to think about Dracula, not just as a horror story, but as a figure of rebellion, a fanged metaphor for resistance against empire and foreign rule.

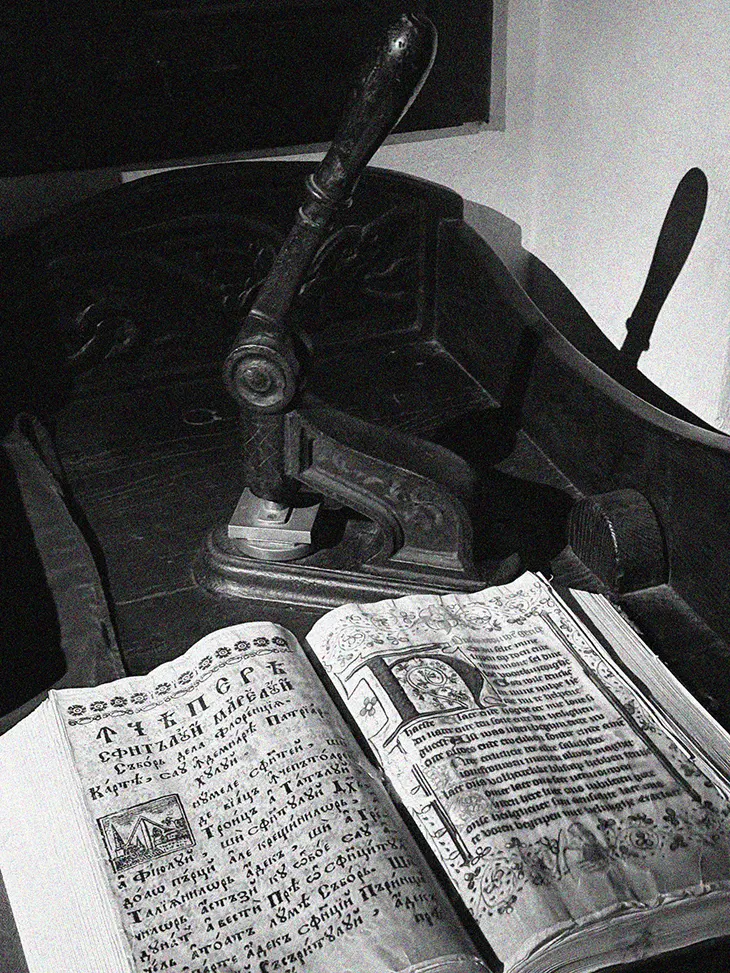

Most people, especially outside Eastern Europe, know Dracula as the creation of Bram Stoker: the aristocratic vampire haunting the imaginations of a Victorian England enthralled by fears of degeneration, invasion, and the foreign unknown. Yet behind the fiction stands a historical figure, and a much more complicated story. Vlad III, known as Vlad Țepeș or Vlad the Impaler, ruled Wallachia in the 15th century, a time when the small principality was squeezed between greater powers, the Ottoman Empire to the south and east, and the Kingdom of Hungary to the north.

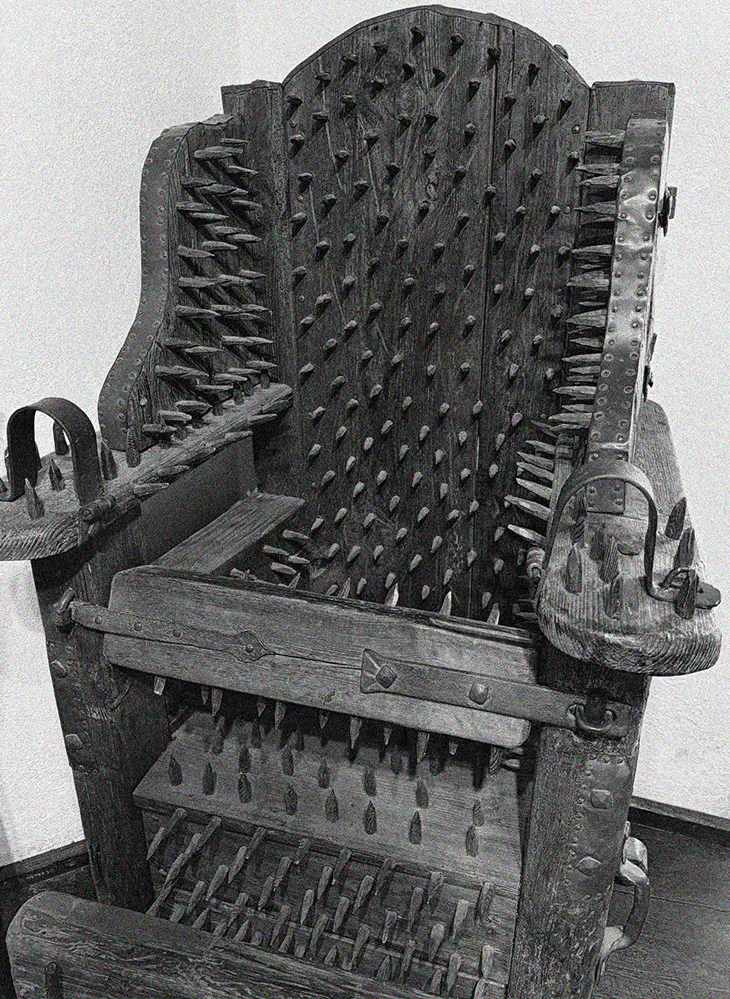

His rule was brutal, by any standard. Yet he also became a symbol, especially in the Romanian cultural memory, of ferocious resistance against Ottoman domination. In that sense, Vlad was defiance embodied: a figure who refused to yield even as larger forces closed in. His reputation for cruelty, especially the impalement of enemies and traitors, became legend. But cruelty was a language understood in his time, a signal to enemies and rivals alike. His historical image was twisted by political necessity: vilified in German pamphlets as a bloodthirsty tyrant, sanctified in Romanian folklore as a protector of the realm. Dracula, the vampire, was born in the space between these conflicting versions.

Bram Stoker never visited Romania. His Dracula is stitched together from second-hand accounts, Victorian fears, and gothic imagination. Yet in linking Vlad Țepeș to the supernatural, Stoker unwittingly amplified a narrative of otherness that already defined the region in Western eyes. Dracula became the ultimate outsider: foreign, unknowable, a threat to British purity and order.

But viewed differently, Dracula also becomes a figure of revenge, a spectral answer to centuries of conquest, colonization, and cultural imposition. In Stoker’s novel, Dracula crosses the sea to invade London, to feed upon the empire itself. It is a reversal of colonial logic: not the civilized venturing into the wild, but the wild seeping back into the heart of empire. He is monstrous, yes, but his monstrosity is the empire’s mirror image.

Walking through Bran Castle, I was struck by how fragile and powerful myths can be. Bran is marketed as “Dracula’s Castle,” but historically, Vlad’s association with it is tenuous at best. There is no evidence that Vlad ever lived there, though he may have passed through. The real fortress of Vlad’s life was further to the east, at Poenari. Yet Bran, perched dramatically on a rocky cliff, fits the imagination perfectly.

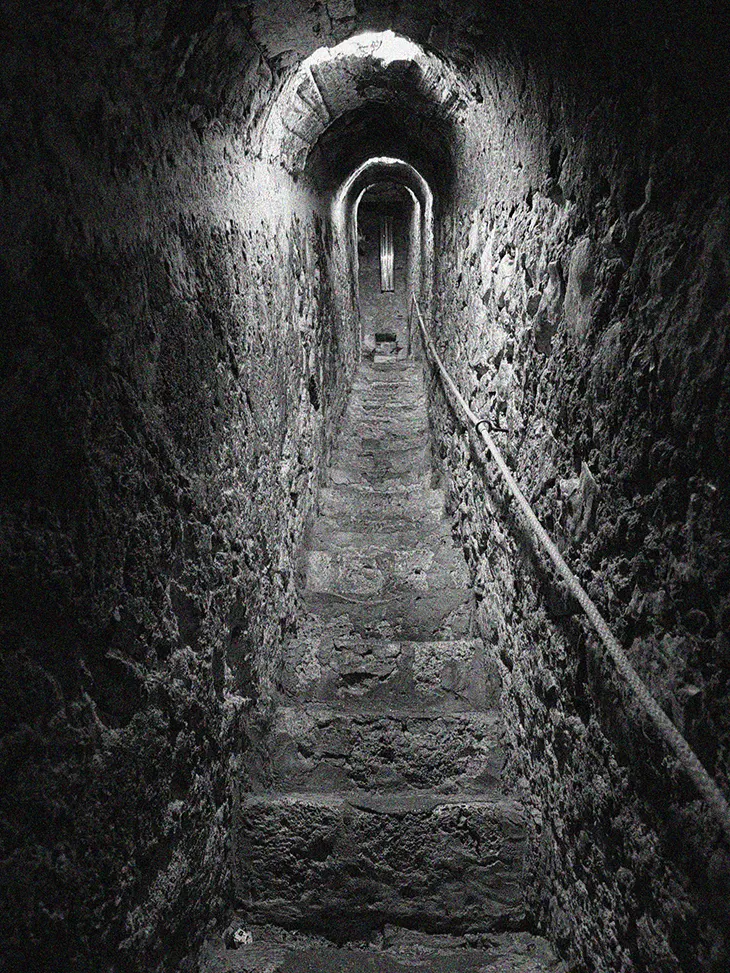

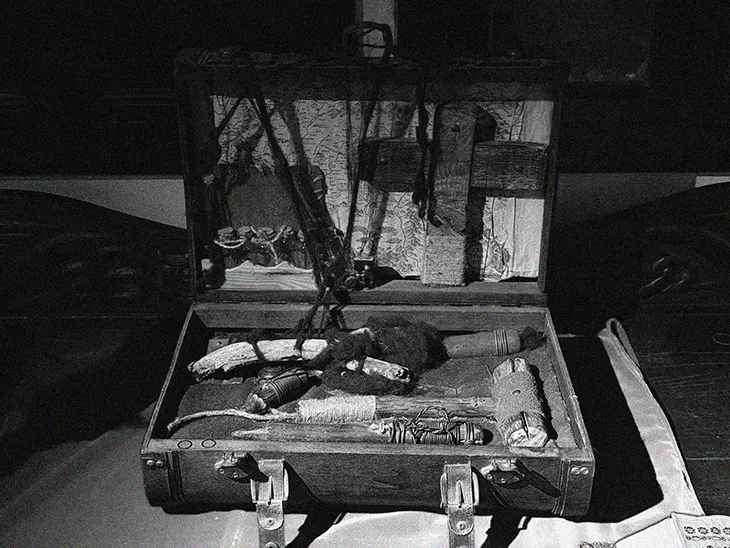

Inside, the castle feels almost intimate. Narrow staircases, low doorways, rooms are arranged around a tight courtyard. There’s none of the sprawling grandeur we associate with Hollywood versions of Dracula. Instead, there is a sense of containment, of layered histories folded into stone. I walked slowly, half lost in thought, watching the snow swirl past the windows. The storm outside blurred the real and the imagined, past and present, much like Dracula himself, a figure who refuses to stay locked within any single time or meaning.

This tension between historical reality and fictional myth is what makes Dracula so enduring. He is adaptable. In every retelling, whether it’s Max Schreck’s rat-faced Nosferatu from 1922, Bela Lugosi’s hypnotic 1931 performance, or the countless reinventions that followed, Dracula morphs into a reflection of the fears and desires of the time.

Now, in 2025, Robert Eggers’ Nosferatu has arrived, a return to gothic roots with a raw, shadow-drenched intensity. The film lingers in silence and texture, capturing the vampire not just as a creature of horror but as a symbol of invasion, exile, and haunted memory. Released in a time when borders, migration, and cultural identity are fraught terrain, this retelling feels eerily in tune with the moment. The vampire’s dual status as both victim and invader has never felt more sharply drawn.

Defiance, at its core, is about refusing the story that is written for you. In that sense, Dracula, both as historical Vlad and fictional vampire, is an icon of defiance. Vlad refused to submit to Ottoman domination, using terror as a political tool. Dracula refuses death itself, rejecting the natural order, feeding on the blood of others to sustain his unnatural survival. Both figures challenge the structures that seek to contain them: empire, history, mortality.

Standing in Bran Castle, it was easy to feel how close these energies still are. Eastern Europe carries a complicated legacy—of being seen as a frontier, a battleground, a periphery to the “civilized” West. Dracula, in his many forms, turns that view inside out. He is the periphery made powerful, the outsider who does not assimilate but instead consumes.

In a world obsessed with purity, order, and control, Dracula is the contamination that cannot be fully eliminated. His defiance is not simply personal; it is existential. He defies categorization, national borders, and even life and death themselves.

In the swirling snow, the idea of Bran Castle felt less like a place and more like a threshold. A portal between histories, identities, and fears. As I drove back through the whiteout, the castle receding into the storm behind me, I kept thinking about that tension. Dracula may be fictional, but what he represents, the refusal to be conquered, to be defined solely by others, feels more real than ever.

Maybe that’s why the vampire persists, across centuries and continents. Not just because he terrifies, but because he whispers to something deep within us: a refusal to be erased, a hunger to rewrite the narrative imposed upon us. In Dracula, the English characters try desperately to categorize, contain, and ultimately destroy the Count. They seek to reassert control over the unknown. Yet Dracula leaves a mark, an infection in the bloodline of empire itself.

Defiance is rarely clean or heroic. It is messy, frightening, often vilified. It takes monstrous forms. To challenge the powers that shape reality is to invite fear and to accept becoming something other than what is permitted. Dracula shows us this, in all his terrible beauty.

In Bran Castle, in the falling snow, it was easy to imagine not just Dracula, but all the ghosts of defiance that refuse to be forgotten. They persist in the stone, in the storm, and in the blood that refuses to freeze, even in the coldest winds.

Words by Katarina Doric.

Originally published in DSCENE Magazine’s “Defiance” Issue: