Harry Nuriev, the visionary founder of Crosby Studios, has established himself as a leading figure in the world of contemporary design. Known for his bold use of color, playful minimalism, and innovative approach to interiors, Nuriev’s work challenges conventional boundaries, creating spaces that feel both imaginative and functional. His signature aesthetic—a mix of vibrant hues, sleek lines, and unconventional materials—has garnered him international acclaim, making Crosby Studios a symbol of modern design ingenuity.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT and DIGITAL

In this exclusive interview for DSCENE Magazine, Harry speaks with editor Katarina Doric about his latest exhibition, “The Foam Room,” and the philosophy guiding his practice. The conversation explores how his concept of “Transformism” continues to shape his work, the role of narrative in reimagining everyday objects, and the balance he strikes between functionality and artistic expression. Nuriev also shares his perspective on the fleeting nature of art in today’s digital age and his belief that magic lies at the core of his creations.

Your work often blurs the lines between art, design, and architecture. Do you see breaking these boundaries as a way to challenge traditional ideas, or is it more about finding new creative freedoms? – It was never intentional. I guess I just tried to find myself, and that’s why I went through so many different areas and eventually ended up in a different medium.

You’ve mentioned that “Transformism” emerged because no existing style could fully capture your approach to design. How does this idea of constant transformation continue to shape your work, and do you see it evolving into something entirely new in the future? – Transformism is an alternative reality that lives in my mind. It’s a fantasy about a future utopia. In this new reality, transformation and repurposing are key; actually, they’re the only creative directions. It can limit my creative plot or open new possibilities.

In previous projects, you’ve recontextualized everyday objects, imbuing them with a new narrative or stripping them of their original one. How do you view the role of narrative in your work? – I enjoy starting with the raw, unbridled nature of an idea before shaping it into a plot or narrative. I find it exciting when an idea takes hold and drives the direction of a future project. As the idea evolves, its subtleties emerge, revealing its true essence, which is crucial. But I especially like the moment just before it’s fully realized.

I believe that logic and art have a complex relationship—it can either pose a threat to art, shed new light on it, or exist independently alongside it.

Your practice often seems to exist in a liminal space between the functional and the purely aesthetic. How do you navigate the tension between creating something that serves a practical purpose and something that exists solely as an artistic expression? – My architectural background will always be one of the important drivers in my work. I believe that logic and art have a complex relationship—it can either pose a threat to art, shed new light on it, or exist independently alongside it.

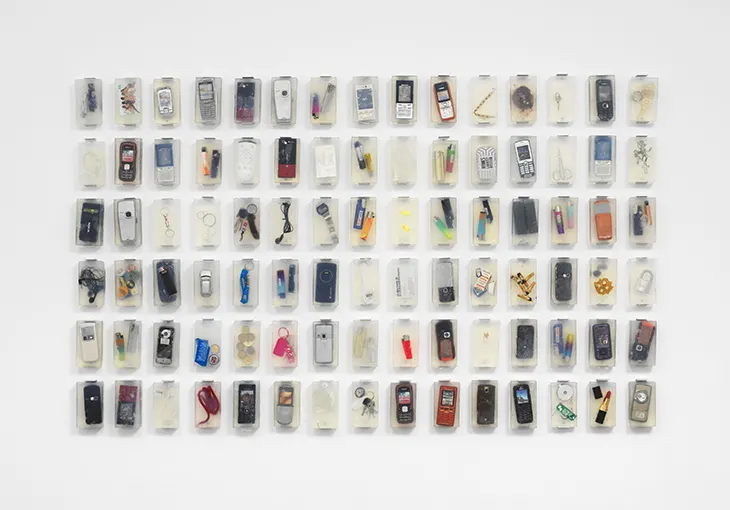

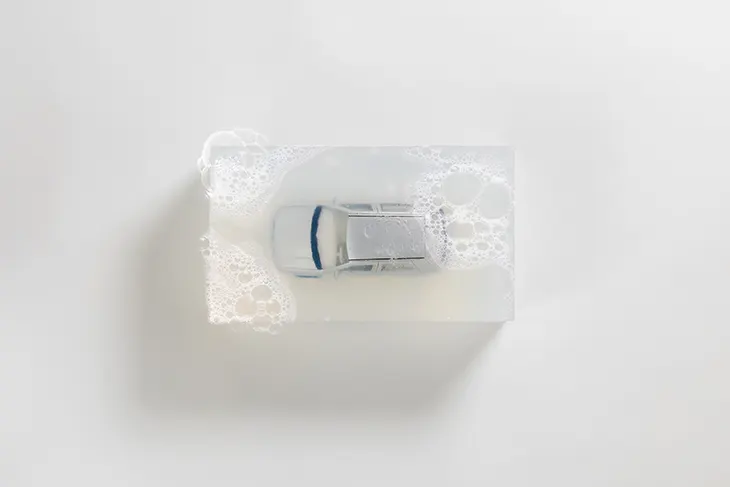

With your new exhibition, The Foam Room, you’ve created an environment that is both playful and deeply ephemeral. How does the use of foam as a material speak to the transient nature of art, commerce, and attention in the digital age? – Foam is something that you can’t actually control. It is different every second; in other words, it has an infinite number of combinations of shapes that are unpredictable, just like clouds in the sky. It’s also very simple at the same time, which I love.

The idea of art as a “party trick” is a powerful critique embedded within the exhibition. How do you navigate the paradox of creating immersive, spectacular experiences while also challenging the superficiality of such spectacles? – I’m drawn towards space and experience before I start working on my art. A party or any social activity is a big component in my work. Creating The Foam Room was a very organic and important continuation of my practice.

Your work often engages the viewer in a multisensory dialogue, where space becomes an active participant. In The Foam Room, how do you see the relationship between the viewer and the artwork? – A foam party, for me, is a staple Berlin souvenir. In our community, everyone has had their moments in the dark rooms. In my work, I always like bridging history and modernity.

I enjoy starting with the raw, unbridled nature of an idea before shaping it into a plot or narrative. I find it exciting when an idea takes hold and drives the direction of a future project.

The Foam Room seems to embody the fleeting nature of modern experiences—intense but short-lived. Do you see this work as a commentary on our current cultural moment? How might this theme evolve in your future projects? – This is what the life of consumption looks like today: accelerating volumes that deliver products nonstop. It’s almost like in Brothers Grimm’s Sweet Porridge—you can’t “stop little pot” and, most importantly, can’t undo what was cooked. This, for me, is a symbol of consumption. Foam perfectly represents it: producing large volumes quickly and then disappearing even faster.

Do you think there are hidden meanings or symbols in your work that even you aren’t fully aware of? – I hope not. That sounds creepy. But there are a lot of things going on in my work.

Do you believe in the power of dreams to influence your creative process? – For me, an idea brings a dream, and this dream motivates an action.

Do you think objects can hold memories or emotions from the past? – I don’t know about memories and emotions, but objects have their own data and karma.

Do you ever feel like your creations take on a life of their own? – I can totally see it.

Do you believe in magic? – That’s all I believe in.

Tell us about your DSCENE cover design. – This is what my creative process usually looks like when I’m working on a space. I mentally empty the room by removing everything and then draw the space in my mind as if starting from a blank canvas.

Originally published in DSCENE Issue 021 “Wicked Wonderland.”

secular brotherhoods of scribes.