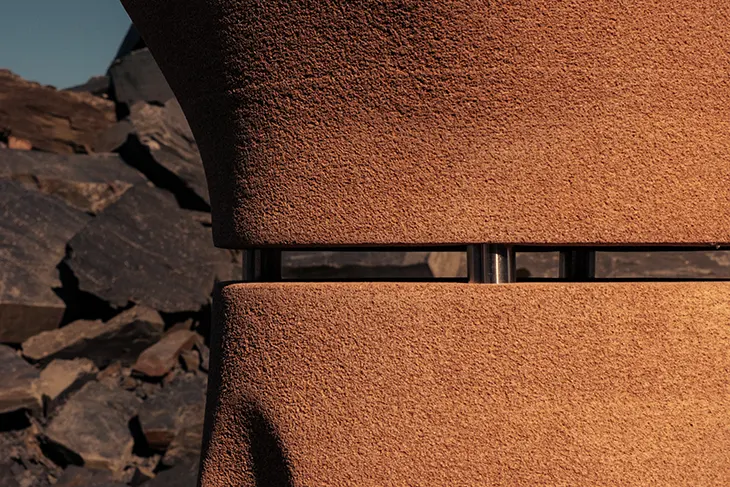

For his 2025 Salone Satellite debut, designer Roc H Biel presented Dust Order, a sculptural exploration of architecture, material tension, and the uncanny. Trained at the Royal College of Art, Biel pushes classical references through a surrealist lens, rendering Corinthian columns and ancient geometries in sand-like textures born from waste. The result is a series of objects that appear caught mid-transformation: a monolithic chair crafted from compacted beech-wood dust, and a modular desk system that morphs from stool to table in a few intuitive moves.

ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

In this conversation, Biel speaks with DSCENE editor Katarina Doric about the aesthetic misdirections, historical echoes, and digital dreamscapes that shape Dust Order, a collection that doesn’t just reference the past, but reinvents it with lightness, contradiction, and sly imagination.

Dust Order transforms architectural waste into sculpture. What first drew you to working with beech-wood dust as a core material? – I originally sketched the collection in stone, very Roman, very heavyweight, but my practice is about folding the familiar into the future. I’m forever hunting that sweet spot where an object feels timeless yet slightly ahead of itself. When the forms started to read like sand sculptures, I wondered: what if they only looked sandy but were made of something entirely different?

Enter beech-wood dust, the kind the workshop hoovers up at day’s end. Compact it and it behaves like wet sand; finish it and it carries a soft, stone-like dignity. Suddenly I had a delicious contradiction: it appears granular, feels monolithic, yet is light, circular, and born of waste. That tension between perception and reality, past and future, was simply irresistible.

I build very real, tangible columns that read as if they’ve wandered straight out of a render. The machine marches toward authenticity; my objects lean toward improbability

There’s a sense of visual contradiction in the chair. How did you achieve the feeling of motion and airiness in something so materially dense? – Two tricks: shifting geometry and strategic negative space. If you trace the chair from bottom to top the profile morphs, octagon into perfect circle into square, so the eye never settles. Then I carved away everything that wasn’t strictly structural, learning from the concept of rhythm used in classical architecture. Light pours through, shadows slide around, and suddenly what began as a solid mass feels as if it’s gently drifting. It’s a bit like watching a time-lapse of erosion, except I’m accelerating the process on purpose.

Your reinterpretation of Corinthian columns feels almost dream-like. What role does surrealism play in how you approach classical forms? – Surrealism, for me, is permission to nudge reality until the mind hesitates. Where Dalí and his peers chased automatism through the subconscious, in 2025 that automatic stream is channeled by algorithms that can spin out a thousand images before lunch. Classical columns give me a baseline of collective memory, we all recognize their proportion and quiet authority. So, while AI-generated images strain to look convincingly real, I flip the script: I build very real, tangible columns that read as if they’ve wandered straight out of a render. The machine marches toward authenticity; my objects lean toward improbability. They meet in a limbo where you’re never quite sure what’s physical and what’s pixel. The result is dream-like familiar enough to feel historic, peculiar enough to seem impossible, and that split-second of uncertainty is exactly where I want the viewer to linger.

You describe Dust Order as being about “wonder” and catching people off guard. What do you think surprises people most when they encounter the pieces in person? – The first surprise is material misidentification: most assume it’s sand-cast or even 3D-printed concrete. When they realize it’s repurposed sawdust their eyebrows jump. The second is levity, people expect heft, then discover they can move the elements without a forklift. That gap between what the eyes tell you and what the hands confirm triggers a little loop of curiosity, disbelief, and delight. Watching that play out in real time at Salone was pure joy.

The desk is modular and reconfigurable, almost like building blocks. How important is adaptability in your approach to design? – Adaptability isn’t a blanket rule for me, each project chooses its own single obsession. Sometimes that’s an emotion, sometimes a material; with the desk it was the idea of structural flexibility. Classical columns already arrive in kit form: the shaft, the capital, the entablature. I borrowed that natural three-part logic, cast each element as a discrete volume, and then asked: how many new “buildings” can you raise if you’re free to shuffle the parts?

I’m forever hunting that sweet spot where an object feels timeless yet slightly ahead of itself.

So I didn’t slice a monolith; I re-imagined historical components as building blocks. The result lets you choreograph the piece, stool one day, bench the next, dining table for a gathering, turning a seemingly static sculpture into a playful spatial tool. Adaptability also future-proofs the work: you can re-script it as your space or lifestyle shifts, which feels honest to the way we live today.

There’s a dialogue between permanence and impermanence, ancient columns reimagined in shifting, digital-inspired forms. What does that say about memory or legacy to you? – Legacy used to be chiseled in stone, immovable, absolute. I’m more interested in a twenty-first-century legacy that can shift, update, and still endure. By giving the columns, a sand-like look yet engineering them to be surprisingly robust, I’m staging a conversation between the long-term and the fleeting. The imagery nods to our fast, almost disposable culture: structures pop up overnight, feeds refresh every minute. But the actual objects refuse to crumble; they outlast the scroll.

So, the work holds hands with past and future at once. It borrows the authority of classical form, then wraps it in a surface that hints at impermanence, almost as if the piece might be blown away with the next swipe. I want that tension to remind us that memory today is an editable sediment rather than fixed marble: we keep layering new experiences, recompressing them into something solid, and then, when the time comes, reshaping it all over again.

Legacy used to be chiseled in stone, immovable, absolute. I’m more interested in a twenty-first-century legacy that can shift, update, and still endure.

Salone Satellite is often a launching pad for young designers. What did it mean for you to debut Dust Order there? – Satellite felt like both validation and open critique. You’re next door to the industry’s big beasts, yet you’re granted a playground to misbehave. Showing Dust Order there put the work under a wonderfully diverse microscope; buyers, curators, students, the odd skeptical carpenter. That real-time feedback loop has already sharpened my thinking about where the project, and my practice, should head next.

You’re part of a generation that moves fluidly between physical and digital. How do you see digital surrealism influencing the future of furniture design? – Digital surrealism is both playground and cautionary tale. On the bright side, it hands us a fresh stage: furniture no longer has to pose in a white void, it can float through nebulae, fracture into particles, carry its own narrative soundtrack. That “wow” moment can spark ideas we’d never reach with a tape-measure alone.

But the same tools breed a cult of flawless renders, surfaces without pores, joins without tolerances. If we chase that hyper-perfection too hard, we start designing objects that can’t survive gravity or daylight, and our eye for real-world texture blurs. The interesting loop is what happens next. A chair shown in a dreamscape may return to the studio with new purpose, because the digital detour altered our perception of it. Likewise, a tangible piece can be “elevated” online, pick up a fresh mythology, and re-enter reality with extra depth. Done thoughtfully, that exchange expands furniture beyond function into storytelling. Done blindly, it risks becoming cosmetic noise. The first impression should dazzle, yes, but the second impression, when you sit down and run a hand over the grain, must feel even better.

I’d love people to walk away thinking, “I’ve never seen wood look like that, and now I can’t unsee it.”

Do you consider Dust Order an art piece, a design object, or something in between. Does that distinction matter to you? – The columns behave like design; the chair flirts shamelessly with sculpture. I’m relaxed about the label because the intent remains the same: to serve a purpose, functional, emotional, or both, while sparking a sense of wonder. If a piece ticks those boxes, I don’t mind which gallery or showroom it ends up in.

If each piece in the collection tells a story, what emotion or thought would you hope lingers with someone after spending time with it? – A quiet, slightly mischievous joy. I’d love people to walk away thinking, “I’ve never seen wood look like that, and now I can’t unsee it.” If the work nudges them to question other assumptions about material, space, or history, then the conversation is still happening long after they leave the room.

What’s next for you? – Next up I’m steering the work into the gallery and collectible sphere, short runs, one-offs, pieces that reward close inspection rather than mass replication. That format lets me obsess over every contour and finish, and it keeps the conversation intimate.

In parallel I’m lining up a couple of collaborations that might push boundaries of perception. The plan is to keep making, keep refining, and keep digging into my reading of the world; every insight eventually filters back into the objects. Continuous curiosity is the engine, the pieces are just its latest snapshots.

Wow he is impressive 🫶

this is stunning! i love when designers seek for something new, bravo Roc! Bravo DSCENE