Everything feels like it’s ending, but quietly. The apocalypse, if it’s here, is polite. It arrives through screens and weather reports, in slow-motion collapses and subtle shortages. Flights are delayed. Produce costs double. Summers stretch too long, winters forget to arrive. We’re living in what I’ve started calling the soft apocalypse, a time when everything is breaking, but tastefully.

DORIC ORDER

It’s strange, this calm unraveling. We still go to gallery openings, buy linen, and talk about summer plans. We post sunsets and skincare routines while the world outside grows hotter, hungrier, more unhinged. The language of disaster has softened into something palatable. Climate change becomes “weather events.” Political collapse becomes “polarization.” Inflation becomes “adjustment.” Our collective denial is designed, curated, filtered for aesthetic appeal.

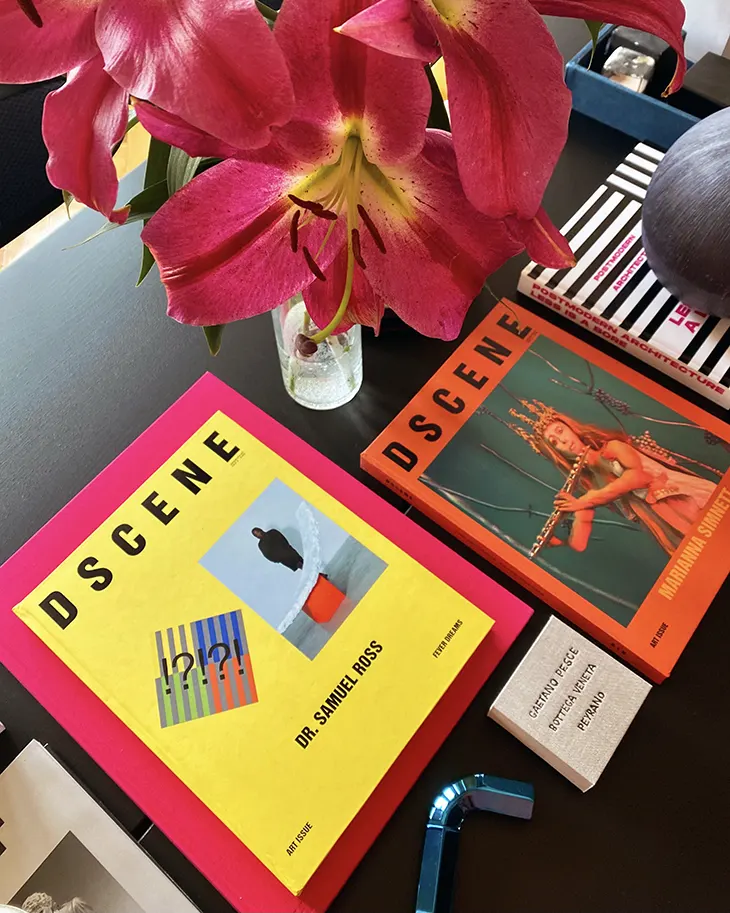

I think about this every time I buy flowers. The florists at my local farmers’ market are always busy, their counters full of tulips in winter and peonies in fall, impossible blooms that arrive from somewhere else. Every bouquet feels like a small act of delusion, pretending the world’s logistics still make sense. But I keep buying them anyway. Maybe because beauty has become our coping mechanism. Maybe because it’s the only way to pretend there’s still time.

The soft apocalypse doesn’t look like fire and ruin. It looks like brunch. It smells like Diptyque candles and sunscreen in December. It’s the curated chaos of living inside systems that are visibly breaking but refusing to admit it. The grid flickers, banks collapse, yet the aesthetic remains intact. Every crisis comes with a color palette. Every disaster gets merch.

The apocalypse, if it’s here, is polite.

Part of this, I think, is generational. Millennials and Gen Z grew up under constant threat, economic recessions, pandemics, climate collapse, and learned to keep going. We were told to work hard, brand ourselves, meditate, hydrate. Now we’re burned out, overeducated, underpaid, and trying to make survival look graceful. The soft apocalypse rewards this. It tells us that maintaining composure is success. That self-care is political. That if we can make collapse look good, maybe it won’t hurt as much.

There’s a quiet feminism in this too, but it’s complicated. Women are expected to keep the world looking functional. We decorate, organize, and soothe while everything disintegrates. The house still smells of bergamot even when the rent’s overdue. We throw dinner parties on melting ice caps. We are the aesthetic infrastructure of denial, turning collapse into something pretty enough to ignore.

I catch myself doing it constantly. Making a table beautiful before guests arrive. Editing photos of the sea to make the horizon look calmer. Rearranging the same objects, pretending it changes something. These gestures feel harmless, but they reveal something deeper: the instinct to curate despair. The belief that if we keep the surface intact, the structure won’t crumble.

And yet, I still feel complicit. My job depends on this surface. I often think about how unimportant my work feels now, writing about design and fashion, describing the details of a $5,000 Balenciaga bag while the world is falling apart. There are days when being anxious about a new issue, about the right shade of paper or cover image, feels wrong. But I still am. I still care. I still scroll through press releases while reading about wildfires. I still find comfort in precision, in editing sentences while everything else feels beyond repair. Maybe that’s what the soft apocalypse does best, it teaches us to keep going through absurdity.

We’re living in a time when everything is breaking, but tastefully.

A few months ago, I went to the student protests in Belgrade. Thousands filled the streets, demanding change. Before leaving my apartment, I stood in front of the mirror, trying to decide what to wear. It felt wrong to carry an expensive bag to a protest, wrong to look like the system I was protesting. I ended up dressing down, slipping on something neutral, something anonymous. But later, I wondered if that, too, was performance. Who decides what solidarity looks like? Does hiding privilege make it less real, or just more palatable?

That day, standing among students holding hand-painted signs, I felt something that had been missing for years, sincerity. The opposite of the soft apocalypse. There was no curation in that crowd, no filtered urgency. Just heat, bodies, chants, real anger. It felt almost old-fashioned, to be somewhere that wasn’t aestheticized. But even there, I caught myself thinking about how it would look in a photo. I can’t tell anymore where the instinct to witness ends and the instinct to perform begins.

The surface is cracking. The soft apocalypse is environmental, political, emotional, economic. Systems that once promised order are now performance art. Democracies vote for chaos. Workplaces pretend to care about mental health while pushing endless labor. Relationships are managed like projects. Everyone is tired, everyone is pretending.

We can’t stop designing our way out of disaster. If we make collapse symmetrical, we think we can survive it.

And yet, we’re still seduced by aesthetics of control, neutral interiors, minimalist wardrobes, smooth skin, slow living. We call it mindfulness, but it’s closer to self-soothing. We can’t stop designing our way out of disaster. If we make collapse symmetrical, we think we can survive it.

Sometimes I envy people who don’t think about it. The ones who still believe in stability, who plan five years ahead. I want to believe in that optimism. But even optimism now feels curated, like an aesthetic moodboard rather than conviction. We aren’t hopeful; we’re performing hope.

When I travel, I notice how similar cities have become. The same cafés, the same furniture, the same beige calm. Everywhere feels like a waiting room. Behind the glass, things are breaking. But the chairs are upholstered in boucle, the pastries are gluten-free, and everyone’s pretending this is normal. It’s a global aesthetic of denial, curated, photogenic, quietly apocalyptic.

The irony is that we’ve aestheticized collapse so effectively that it feels rude to panic. Panic is messy. It doesn’t photograph well. It doesn’t sell. So we light candles instead. We learn to speak calmly about extinction. We rebrand despair as awareness.

The soft apocalypse is quiet partly because it’s human. It’s the instinct to survive with grace, even when grace feels absurd.

I’m not immune to it. I edit the anxiety out of my own life. I buy refillable bottles, scroll through climate reports, read about sustainability while ordering items made thousands of miles away. The contradictions have become unremarkable. We all live in them. The apocalypse has been absorbed into routine.

But there’s also something tender here, the human desire to make things bearable. We still paint our nails, cook dinner, love each other, care for our plants. We keep routines because we need continuity. The soft apocalypse is quiet partly because it’s human. It’s the instinct to survive with grace, even when grace feels absurd.

Sometimes I think the only honest response is to start being messier. To admit the fear. To stop pretending the end of things must look beautiful. Feminism, art, design, everything we love, will have to find new forms when beauty itself becomes a kind of denial. Maybe the point is not to make the apocalypse aesthetic, but to make it visible.

Maybe that’s what survival looks like now, learning to live beautifully at the edge of disaster, without pretending the edge isn’t there.

The soft apocalypse is seductive because it feels civilized. No screaming, no sirens, just polite collapse. You can have climate grief and still wear cashmere. You can despair about inequality and still order artisanal olive oil. The contradictions keep us sane. They also keep us numb.

I don’t think the apocalypse will ever feel like one. It will arrive like this: slowly, quietly, beautifully. Through another heatwave. Another headline. Another brunch. We’ll keep buying flowers, keep making things look nice, keep talking about “balance.” And maybe that’s what survival looks like now, learning to live beautifully at the edge of disaster, without pretending the edge isn’t there.