Yixuan Liu and Yilin Zhang have established rigorous professional trajectories in their fields, serving as lead designers on major firm projects.

Yixuan Liu serves as Design Lead at MH Architects, directing coordination and key decisions from early conceptual framing and spatial strategy to material articulation and realization. She leads the development of core design questions, defines each project’s conceptual and perceptual framework, and coordinates interdisciplinary teams to ensure psychological perception, bodily scale, and temporal experience remain central throughout the process.

ARCHITECTURE

Yilin Zhang serves as Project Lead at Studio Architecture, directing high-density office developments and complex technical integrations from structural coordination through material performance and environmental systems strategy. She leads core decision-making across technical execution, translating ambitious spatial concepts into precise, buildable systems that ensure long-term performance consistency and structural reliability at scale.

Beyond their firms, they operate as a complementary dual-core collaboration across hospice, experimental, hospitality, and residential work. Their partnership centers on a fundamental question: how architecture responds to human presence over time. Whether addressing dignity and companionship in end-of-life care or shaping perceptual order in everyday environments, they prioritize psychological perception, bodily scale, and temporal experience as core design drivers. This is not an added narrative layer, but a foundational framework guiding concept development, material selection, and structural strategy.

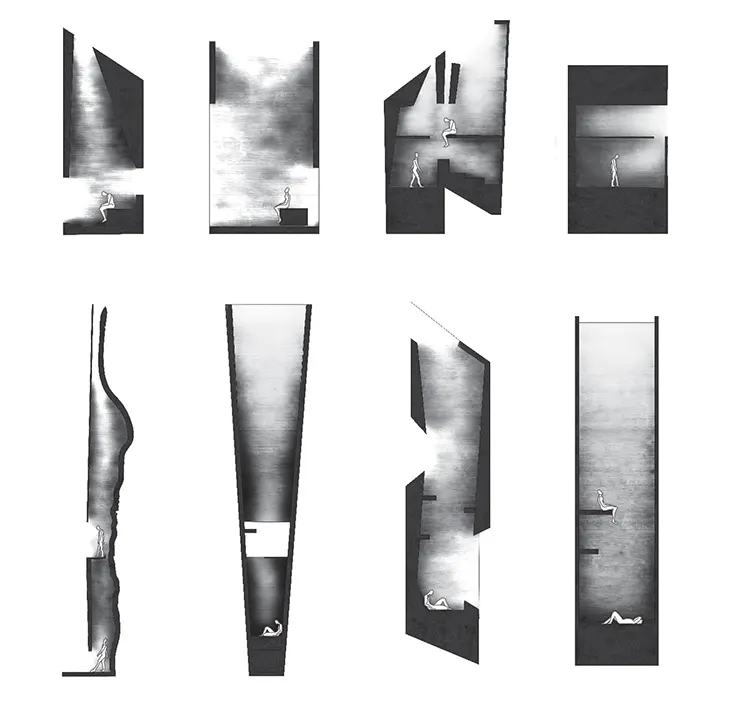

Their collaborative work has been recognized through competitive international platforms and institutional exhibitions. Almost Forgotten was exhibited at Sir John Soane’s Museum in 2026 as part of its public curatorial program and presented through London Creates in 2025. The project was also awarded Winner, The Drawing Prize 2025 by the World Architecture Festival, recognizing excellence in conceptual architectural drawing internationally.

Editorial commentary positioned their work within a renewed discourse on drawing as an operative architectural medium rather than a representational afterthought. By integrating conceptual rigor with technical precision, Liu and Zhang demonstrate a rare dual capacity: advancing spatial theory while maintaining architectural clarity. Their selection by leading institutions underscores not only the originality of their methodology but also its relevance to contemporary debates on perception, memory, and the ethics of spatial practice.

In Almost Forgotten, your use of The Art of Memory has been widely praised for reactivating a classical mnemonic system as an innovative methodology. Critics have particularly noted the discipline with which you avoided turning memory into image or symbolism. How did you operationalize a system rooted in mental architecture into a precise and buildable spatial framework while maintaining that conceptual restraint?

Yixuan: In the contemporary context, The Art of Memory is often reduced to a citable reference where design “narrates memory” through monuments or symbols. Memory becomes a theme that architecture illustrates.

Our position is more radical. I interpret The Art of Memory as a system of cognitive structure: offering not imagery, but spatial organization encoded through sequence and position. I reject symbolic language, treating memory as an operational spatial algorithm. The question is whether architecture can generate memory itself.

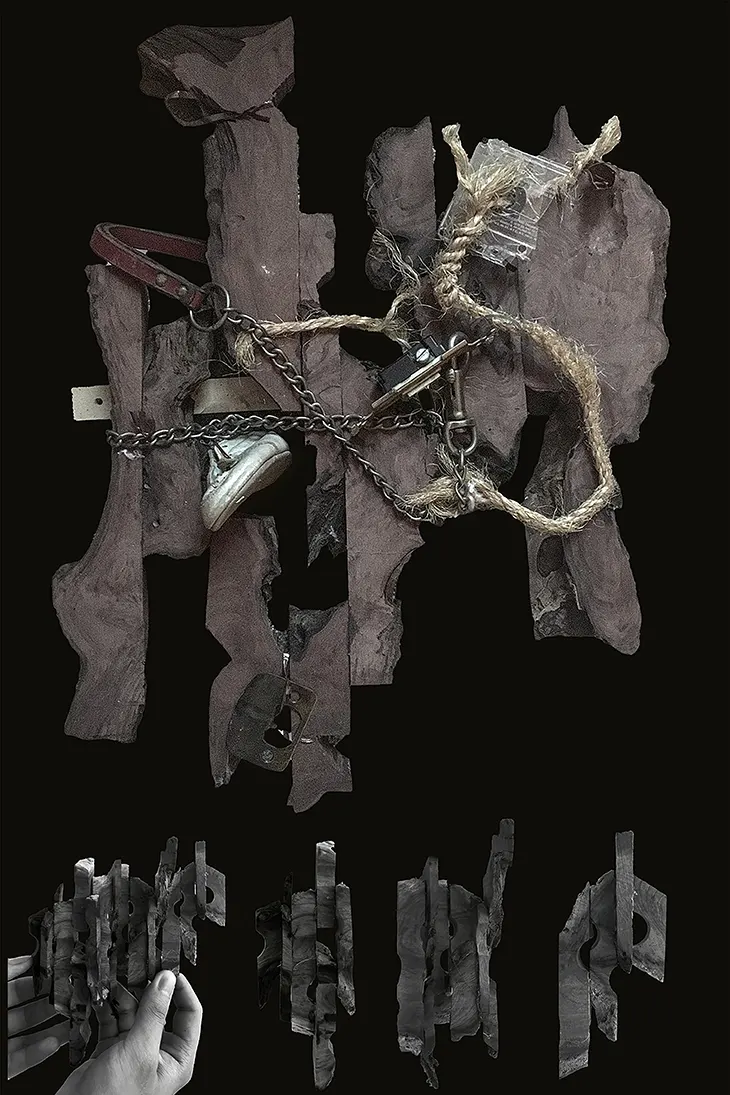

I therefore transform drawing from representation into a research tool to study how movement and sightlines form cognitive paths. Inspired by my abstract drawings and Yilin’s timber sculptures, we test how mass and light shape orientation and emotion. These media are not expressive. They refine spatial logic. Ultimately, we translate these findings into a buildable volumetric order, where memory becomes a constructed spatial logic grounded in human emotional experience rather than symbolic reference.

Yilin: As design transitioned from sculptural experiments to architectural abstraction, technical translation became critical. Yixuan’s spatial logic required large-scale volumes while maintaining emotional intensity. I ensure resonance through structure and materiality. The originality lies in translating “how humans remember” into a buildable, precise system, addressing the lack of humanistic care in contemporary architecture.

Unlike conventional projects, your project treats absence as structural rather than residual. When did void shift from being an outcome of subtraction to becoming a primary generative force in your design logic?

Yilin: That’s right. In most projects, space is enclosed by physical entities, where arranging functions and volumes leaves the “void” as a passive consequence. We deliberately reversed this sequence.

We propose designing the “void” first. I define its extent, proportion, and rhythm, exploring how it receives light, forms shadows, and transforms over time. Solid mass is no longer the protagonist; it reinforces the boundaries of the void. Walls and structures exist to clarify the “void” rather than occupy space. This is not abstract. I transform the “void” into a controllable system, testing material reflectivity and adjusting openings to ensure the space is not hollow emptiness, but a dense emotional container enveloping the body.

We do not generate architecture through accumulating matter; instead, we generate structure by “defining absence,” allowing human experience to become the starting point of spatial logic.

Yixuan: Treating the void as a generative force re-evaluates architectural values. Contemporary architecture prioritizes efficiency and functional maximization, leading to the continuous compression of the void. However, deep human experience occurs in pauses, intervals, and negative space. By deciding on “subtraction” as the generative logic, we are redefining the most important part of architecture. This is a shift in generative logic rather than merely a formal choice.

The collaboration is framed as bidirectional calibration rather than division of labor. Can you describe a specific moment when artistic intuition and technical reasoning directly conflicted, and how that tension refined the project?

Yixuan: In many architectural collaborations, a linear sequence separates concept and technology: one proposes a vision, the other executes structure. Ideas raise questions and technology answers them; both function, but rarely transform each other. Our collaboration operates as a “dual-core structure.” I propose core questions and spatial prototypes, establishing generative logic through experimentation and preserving tension for theoretical progress. Yilin works from material systems, reorganizing tectonic paths to stabilize and reinpire me regarding these prototypes.

The key is continuous mutual calibration. Ideas and technology no longer follow a master-servant model but iteratively shape each other, maintaining theoretical sharpness and tectonic rigor.

Yilin: Refining the “suspended components” illustrates our approach. Conventional practice adds visible supports to heavy volumes, sacrificing immersion. Therefore, we fundamentally changed the approach: we tested ultimate load capacities through physical models and designed a concealed metal anchoring system.

The transfer of forces is hidden, allowing heavy timber panels to manifest an anti-intuitive state—as if “about to fall, yet absolutely stable.” This misalignment between vision and gravity triggers psychological tension in the observer. This is not merely a technical correction, but a process where I proactively create spatial emotion through physical construction. It is precisely this physical deduction, with human perception as the starting point, that provides the realistic foundation for Yixuan to refine her spatial theories.

In a profession driven by efficiency and optimization, Almost Forgotten proposes a slower, iterative model. Do you see this as a critique of contemporary architectural production, or as an alternative working system within it?

Yixuan: I see it as both a reflection and a position. Contemporary architectural production prioritizes efficiency and time compression; design becomes a race, and spatial experience is reduced to metrics. Within this logic, human perception, emotion, and memory are often marginalized.

In Almost Forgotten, we intentionally slowed down because we value authentic human experience over drawing completion rates. By adjusting scale, light, and bodily movement, we let space be perceived before it is finalized. This approach grounds design decisions in subtle human responses rather than the pursuit of formal efficiency.

This is not only a response to the speed-first model but also a humanistic stance. Architecture should engage the depth of the human spirit and perception, rather than merely meeting calculable optimization goals.

Yilin: This is not an abstract ideal but a constructed working system. Unlike traditional workflows, where structure and lighting are treated as passive remedies, we introduce material and atmospheric testing before determining the final form. This ensures these elements actively participate in early decision-making.

The uniqueness lies in incorporating human perception into the technical process. By verifying material performance and spatial proportions, we redefine efficiency as keeping concept, technology, and experience aligned. Consequently, this “slowness” is not a rejection of the industry, but a reordering of priorities, returning architectural production to a foundation of care for the individual.

The project positions architecture as a framing device for memory rather than a producer of meaning. How does this reposition authorship? Are you designing form, or conditions for perception?

Yilin: When architecture becomes a “viewfinder for memory,” authorship shifts from creating form to ensuring perceptual conditions operate precisely and reliably. This requires careful control of often-overlooked physical factors, acoustics, material temperature, texture, and glare, because any inconsistency can destabilize the perceptual framework. My role is to integrate these elements into a coherent physical system that sustains experiential continuity across scales and prevents technical imbalance from undermining the experience.

Yixuan: We design conditions for perception rather than prescribing meaning. Instead of embedding a fixed narrative, we construct a precise order of proportion, movement, and light that allows meaning to emerge through individual experience. This redefines authorship: the architect becomes the orchestrator of a perceptual framework, positioning memory and perception as active design drivers rather than symbolic additions.

Your work has received international recognition, including exhibition at Sir John Soane’s Museum and the distinction of Winner, The Drawing Prize by World Architecture Festival. Within these curatorial and competitive contexts, how was Almost Forgotten framed, and which aspects of your authorship and methodological approach do you believe most clearly distinguished the project in the eyes of curators and juries?

Yilin: Almost Forgotten has received recognition on international platforms largely because it transforms The Art of Memory from an abstract cognitive system into a perceivable spatial experience, while achieving a precise integration of concept and technical execution. I led the translation of spatial logic into buildable systems, ensuring that materials, structure, and light environment enhance the users’ sensory experience. This approach, balancing technical rigor with perceptual engagement, allows the architecture to function not only as a physical space but also as a medium for emotion and cognition.

Yixuan: As architects who have also served on international juries, we understand that curators and evaluators prioritize originality and humanistic depth over purely symbolic narratives. Almost Forgotten has been praised for embedding psychological perception, bodily scale, and temporal experience into spatial generation, making the architecture an active field where participants can engage with memory. Its depth and conceptual rigor distinguish it within contemporary architectural discourse.

Within the structure of large architectural practices, design leadership often operates through layered decision-making and cross-disciplinary coordination. How do you navigate your role when conceptual intent must align with structural systems, environmental performance, and client requirements?

Yixuan: At MH Architects, I lead at the intersection of design and construction, directing projects through both conceptual authorship and technical precision. As Design Lead, I establish the conceptual thesis and spatial agenda that set the direction for all subsequent decisions, treating design as the construction of an intellectual and perceptual system.

Rather than simply integrating vision and execution, I design the structure within which execution operates. By embedding performance parameters, material behavior, and construction intelligence into the project’s early structure, I ensure that innovation is systemic rather than cosmetic. Crucially, these technical systems are calibrated to support human experience: how space is felt, inhabited, and remembered over time. My leadership defines the rules of engagement so that technical development extends conceptual and human intent, rather than correcting it.

Yilin: As a California-licensed architect, my role requires a comprehensive vision for multidisciplinary coordination. In large projects, I lead the implementation of the core design. Industry norms often sacrifice spatial perception when concepts face structural or environmental constraints. I do not accept such technical compromises. Instead, I intervene early in the logic of mechanical, electrical, and structural systems, guiding engineers to transform technical constraints into conditions that support spatial emotion.

This is where I exercise my role as the project lead: not by overriding other disciplines, but through strategic coordination and early involvement, ensuring that in complex commercial projects, authentic human experience remains the anchor of all technical decisions.

In a profession increasingly driven by speed, metrics, and visual consumption, Yixuan Liu and Yilin Zhang move in the opposite direction. Their work does not decorate memory. Instead, it constructs it. By treating the void as structure and perception as architecture’s true material, they challenge the discipline’s fixation on object and image. Concept and construction operate as one system, not a hierarchy. Almost Forgotten is more than an award-winning project. It signals a generational shift: a practice where human experience is not an afterthought, but the foundation.

Interview by DSCENE Editor Maya Lane.