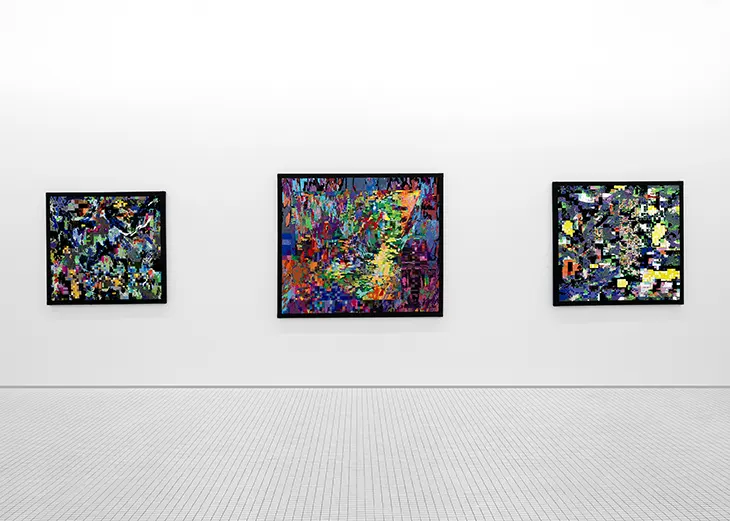

Basil Kincaid ’s work resists categorization, moving fluidly between quilting, drawing and photography, to construct complex compositions. With Inward Cartography: Self of Selves, now on view at Library Street Collective, Kincaid charts a new body of work that uses the language of textiles to explore personal transformation, ancestral memory, and the fluid boundaries of identity. Developed between two continents, the pieces collapse the distance between physical process and digital influence, the outer universe and inner world.

INTERVIEWS

In this exclusive interview for DSCENE Magazine, Anastasija Pavic speaks with Basil Kincaid about the ideas behind the exhibition and the layered approach that informs the work. Touching on ritual, language, technology, and the metaphysical weight of materials, the conversation offers a glimpse into a practice grounded in intuition and guided by a constant reimagining of selfhood.

Quilting runs seven generations deep in your family. Do you use any digital tools to evolve the medium while still honoring that lineage?

I don’t use digital tools for quilting, not even a rotary cutter. My tools reflect what my grandmother and her sisters used: scissors, needle, thread, sewing machine. For me, evolving the practice means expanding on what I see as the core tenets of quilting—memorial content, reuse, simple tools, collective action, layering, rhythm, and repetition.

I use personal or donated clothing with emotional weight and collect discarded materials that would otherwise end up in landfills. Like my grandmother, I work both alone and with others. In St. Louis, many people have volunteered to help with my quilts.

Traditional quilts have three layers, mine sometimes have up to sixteen. I don’t use patterns, but work improvisationally, guided by rhythm and repetition. While I’m open to digital tools for fabric creation, my focus is on deepening the core values of quilting. Maybe it’s less about evolution and more about continuing the conversation, adding my voice to a practice that’s been in my family for generations.

How do you sense when a material is ready to be transformed?

I’m constantly collecting material, so when it’s time to work, I just reach for what catches my eye, or my heart—out of my collection. As for when I retire my own clothes, it’s usually because I grow out of them. I used to be really skinny, since I started quilting, I’ve gained 40 lbs of muscle. As I train and my body changes, my old clothes no longer fit, so they naturally end up in quilts. You know when it’s time to shed skin. If a garment no longer brings me joy, it ends up in a quilt, and then brings new joy.

Material transformation always follows internal or personal transformation. When I change, I see things differently. Something I may have felt overwhelmingly attached to might lose parts of that bond. The fragmentation and restructuring of the garment or material mirrors the shapeshifting of my internal structure. No energy is lost or discarded, just rearranged to make new forms.

How do you see the emotional residue in found or donated fabrics shaping the final energy of a work?

That part can be metaphorical, representing the potential beauty of our interdependence. We’re all different for a reason. Those differences in ability and perspective allow for a vastness in our experience of life. Each person walks their own path with different stimuli activating the same chromatic set of emotions. With the quilt, I’m imagining each sensation as a color on a spectrum. Each varied fabric texture becomes a unique memory that sparked that feeling.

I like thinking about the potential we have within humanity. All of our experiences can bring value to the whole. We’re often encouraged to believe that individual actions don’t add up to much in the face of larger systems. But I believe we are constantly impacting the whole, through our actions and our being.

As for the quilt, I may not know the specifics of each memory or individual piece of fabric, but I know the clothes were worn. They witnessed the love, the sweat, the joy, and the pain of the people who wore them. That energy has a weight to it, it’s palpable when you stand in front of one of the quilts.

Much of your recent work moves between digital and physical spheres, beginning with hand drawing, then digitizing and finally embroidering. How does this hybrid process reflect the multiplicity of self you reference in your latest exhibition?

Yes, the process of arriving at my final embroidery works dances between digital and physical techniques. Part of this journey was realizing the validity of digital painting and its ability to convey emotion in ways I thought only physical media could. Today, it’s hard not to consider our digital lives, especially as artists. This led to personal observations. One was that I had used digital tools for documentation and distribution but had denied the computer’s creative capacity in fine art.

Outside of the art world, I create board games and card games. I learned Photoshop and Illustrator while prototyping those games. As I work toward unifying the parts of myself, I noticed that the skills I developed for games were becoming applicable to my artmaking. I also think about how we express ourselves in digital spaces, how we perform when we play, and how we express ourselves IRL. I have more questions than answers. Creating this body of work made me ask how important digital life is to an artist’s career. I’m still not sure.

The core of this process for me is translation and trust, trusting that even though any expression is only a curated selection, the essence will still connect.

You often refer to your work as spiritual technology. What does that phrase mean to you?

I like to look at the function of creative pursuits before they became commodities. I started thinking about spiritual technology around the time I deepened my investigation into quilts. As I began to sleep with my own quilts, or quilts that had been gifted to me, I noticed how they impacted the quality of my sleep, the potency of my dreaming, and my dream recall. In that example, dreaming is one of our core abilities, and quilts, as a tool of spiritual tech, amplify that ability.

To me, spiritual technologies repair and advance some of our deeply human traits and abilities that have been diminished or atrophied, helping us recover the memory of our true nature. That’s why collective song and dance are so powerful, both are spiritual techniques. The process of making a quilt, especially one made with personal materials from relationships, loved ones, and pivotal moments in my life, forces me to relive memories and revisit past choices, grappling with time and its passage, the beauty, joy, and pain of it all.

“Maybe it’s less about evolution and more about continuing the conversation, adding my voice to a practice that’s been in my family for generations.”

You’ve cited writers like Octavia Butler and Legacy Russell as inspirations. How does literature, particularly theoretical writing, inform your creative process?

Literature and writers help me understand my work and myself more after the work is created than during the actual process of making it. That said, reading about Octavia Butler’s life and the way she spoke about writing has reaffirmed the way I think and work as an artist.

Writers like Butler and Russell expand my sense of possibility and have amplified my confidence. I’ve been comforted and called to action by Legacy Russell’s manifesto. I felt seen in that text; it gave language to a myriad of feelings I hadn’t yet been able to articulate. Now, when I’m creating, it’s pure play. I don’t have to go through the mental gymnastics of second-guessing. What I’ve learned from Octavia Butler is to apply consistent pressure, then edit down.

In Inward Cartography: Self of Selves, you use the metaphor of a 30,000-foot aerial view to map internal terrain. What does that perspective reveal that a grounded one might not?

This might be easier to explain with a diagram, it’s about the simultaneous plurality of perspectives within our being. When my eyes are open, I feel grounded. I see the outer world around me. But when I close my eyes, I feel the vastness of my interior. That’s where the sensation of the 30,000-foot view blossoms. It’s the view of looking inward and realizing you could go down and down forever, exploring more of yourself.

Our outer eyes have a limited field and depth of vision, defined by our biology and how we’ve trained ourselves to see and process the exterior world. Looking out makes me feel small, and that’s important, to remember my place in everything. But looking in makes me feel infinite, and that’s also important. I am a grain of sand and a galaxy.

These new works explore the emotional defragmentation of suppressed feelings. Can you walk us through how that inner disassembly takes shape visually?

The idea of emotional defragmentation began with using polygonal shapes that interrupt the flow of my natural lines. These forms can suggest pixelation, but I also see them as compartments or temporary containers. The rectilinear areas offer visual rest, while the hand-drawn lines keep the eye moving. I can’t access all of myself at once, only fragments, like holding a partial hand of cards. Some memories stay, others fade.

Through color, shape, and texture, I try to reflect what it feels like to sort through those internal layers. Organization is always temporary, like trying to arrange a star system or river delta by hand. The works shift visually, much like memory does, recollection becomes recreation. At its core, defragmentation means being willing to look inward, even when it’s difficult.

“I may not know the specifics of each memory or individual piece of fabric, but I know the clothes were worn. They witnessed the love, the sweat, the joy, and the pain of the people who wore them. That energy has a weight to it, it’s palpable when you stand in front of one of the quilts.“

If these embroidered maps are a guide, where do you hope they lead the viewer?

They aren’t literal maps, they explore the idea of mapping uncharted inner terrain. There’s no fixed guide to the internal landscape, and as I map mine, it continues to shift.

The viewer moves alongside me. As I go inward, they enter their own inner spaces. Memories surface differently for everyone. I think about which moments I’ve preserved, and which I’ve hidden.

This work isn’t about leading. It’s about wandering. The uncertainty creates a space of mutual trust, where both viewer and artist can discover something new. My hope is that each person feels invited to explore their own interior, with the courage to confront what they find.

The art world often favors labels and boundaries, yet your work defies them. What does freedom mean to you in that environment?

thanks