The girlboss was supposed to save us. She wore heels, carried a MacBook, drank overpriced lattes, and smiled through twelve-hour work days. She turned ambition into aesthetic: marble desks, pink blazers, motivational quotes in gold font. She told us exhaustion was chic. Ten years later, she’s dead, killed by burnout, bankruptcy, and Twitter memes. And yet, like a bad ex, she keeps texting.

DORIC ORDER

I was in my twenties when the myth was at its peak. Everyone I knew was hustling. PR girls running around in Zara heels, interns paid in tote bags, assistants living on iced coffee and “exposure.” If you were tired, you weren’t oppressed, you were “building your brand.” Your suffering was empowerment. If you collapsed on your laptop at midnight, congratulations, you were officially a girlboss.

A decade later, the girlboss has vanished. Nobody wants to be her anymore. Not the women just starting their careers, not the ones already deep into them. She died of overexposure. She became cringe, meme fodder, shorthand for burnout and exploitation. And yet, as with all cultural deaths, her absence hasn’t created liberation. She has been replaced, just not by anything better.

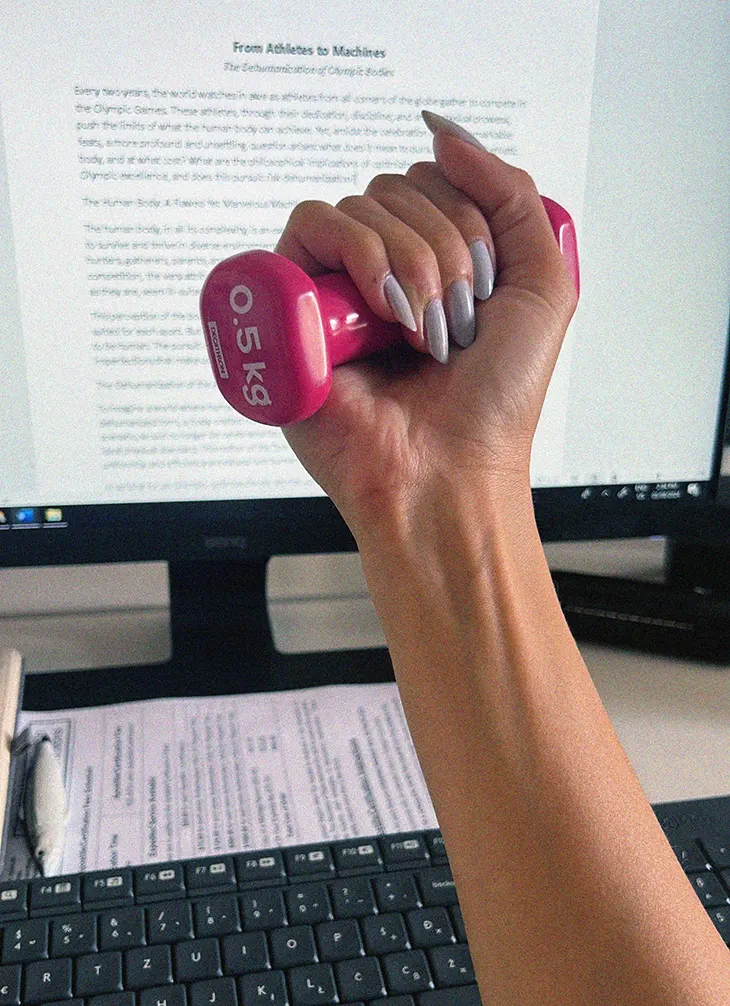

The girlboss era was clear about its demands. Work constantly. Monetize everything. Smile through it. Today, the replacement archetypes are murkier, but just as suffocating. You can’t post about #slaytheday anymore without irony, but you are expected to optimize. No one’s telling you to rise and grind, but everyone is telling you to sleep eight hours, track your cycle, walk 10,000 steps, meditate, journal, hydrate, and of course, post proof that you’re doing all of this. The grind didn’t die. It rebranded as wellness.

Ten years later, the girlboss is dead, killed by burnout, bankruptcy, and Twitter memes. And yet, like a bad ex, she keeps texting.

What strikes me most is how quickly the script flipped. In the 2010s, ambition was spectacle. It had hashtags, merch, an aesthetic that made burnout aspirational. Now, productivity hides under soft beige tones and the word “balance.” Instead of posting about 18-hour days, women post about early bedtimes and skincare routines. Instead of telling you to hustle, they tell you to manifest. But the pressure feels the same. You are still expected to make your life look photogenic, still expected to show that you’re doing everything right, still expected to optimize yourself into the perfect worker, mother, partner, citizen.

The girlboss may have been embarrassing, but at least she was obvious. Her water bottles screamed #girlpower in metallic fonts. Her offices had neon signs that read “Work Hard Play Hard.” The new archetype is subtler, harder to critique, because it disguises itself as care. Who can argue against hydration? Against journaling? Against getting enough sleep? Yet the perfectionism is relentless. You’re not allowed to just be tired anymore. You have to demonstrate you are tired responsibly.

Sometimes I miss the transparency of the girlboss era. It was ridiculous, yes, but it told the truth: power was tied to overwork. Today, the overwork is still there, but it’s hidden under yoga mats and pastel planners. Women are expected to look like they are not working while still working constantly. That is the cruelest trick of all.

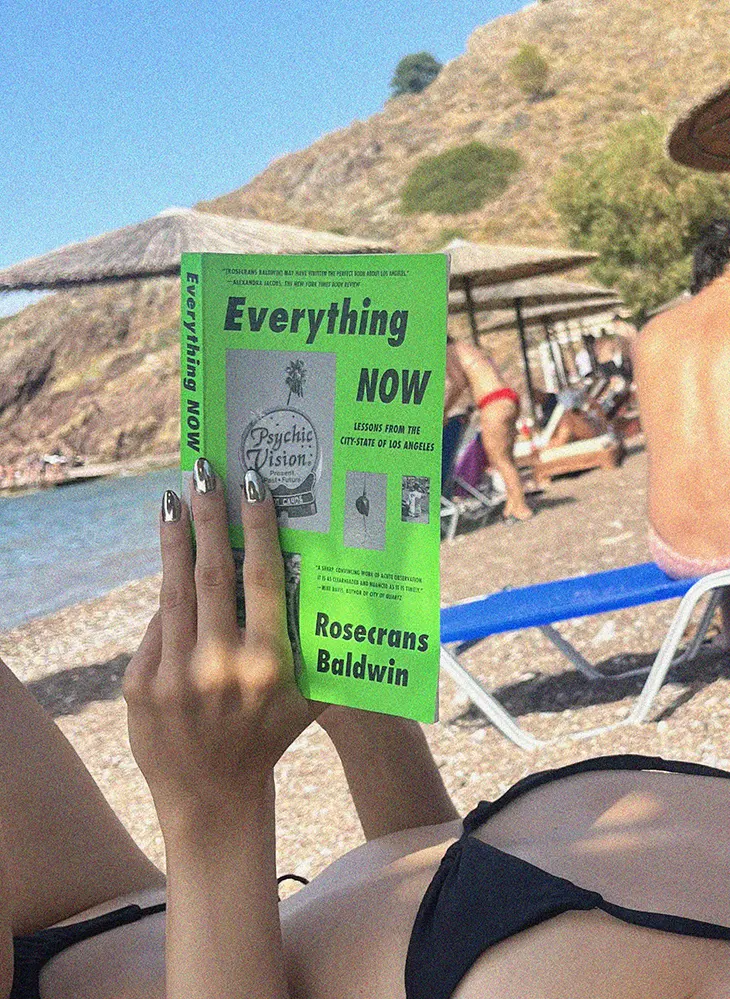

And if it’s not wellness, it’s the side hustle. You don’t have to be a CEO, but you do have to be your own little economy. Sell clothes on Depop, run a newsletter, freelance, make candles, DJ on weekends. Every hobby is a potential revenue stream. Every interest is something to brand. The line between work and life doesn’t blur anymore; it evaporates. The myth of the girlboss told us we could build empires. The new myth tells us we must monetize survival.

The new myth tells us we must monetize survival.

I notice this especially in my own field, where side projects are expected. It’s not enough to write, you have to also post, curate, photograph, host. To stay visible, you need to produce content about your content. The girlboss held endless meetings. Her replacement lives online endlessly. Different stage, same exhaustion.

There’s another shift too: the aesthetic of success. When I was younger, the career woman was cinematic. I grew up on characters like Miranda Priestly, Elle Woods, Andy Sachs, women whose ambition was packaged in Prada coats and courtroom speeches. Their stress was glamorous. Today, the archetype has changed. Success looks like minimalism, chipped nails in candid selfies, influencers eating fruit in sweatpants. The performance is no longer “look at how hard I work.” It’s “look at how casual I am while still being rich.”

I don’t believe this is progress. It’s just a new mask. Women are still trapped in archetypes, still expected to present a life that fits into cultural scripts. The only difference is that ambition has become harder to name. To be visibly career-driven is cringe. To be visibly exhausted is embarrassing. So women are asked to hide ambition under layers of wellness and relatability. The performance is subtler, but it is still performance.

Women are still trapped in archetypes, still expected to perform their way into freedom.

What’s missing in all of this is honesty about class. The girlboss was always a fantasy for women who started with money. Her replacements are too. Skincare fridges, circadian rhythm lamps, casual selfies in expensive apartments, aren’t universal. They’re just new versions of the same fantasy: if you consume correctly, you’ll be free.

I am older now, and maybe more jaded. I no longer believe that the right planner, the right supplement, the right tote bag will unlock liberation. I still work too much, but I don’t dress it up in hashtags. I don’t want to be a girlboss. I also don’t want to be her wellness-optimized successor. I want a life that isn’t performance.

The myth of the girlboss was ridiculous, but the myths replacing her are insidious. They hide under self-care, relatability, and wellness, disguising overwork as balance. They make ambition invisible while still demanding perfection. They convince women that liberation is personal optimization rather than structural change.

The girlboss is dead. But don’t mistake her death for freedom.

So yes, the girlboss is dead. But don’t mistake her death for freedom. What came after her is smoother, prettier, subtler, and in some ways, even harder to escape.