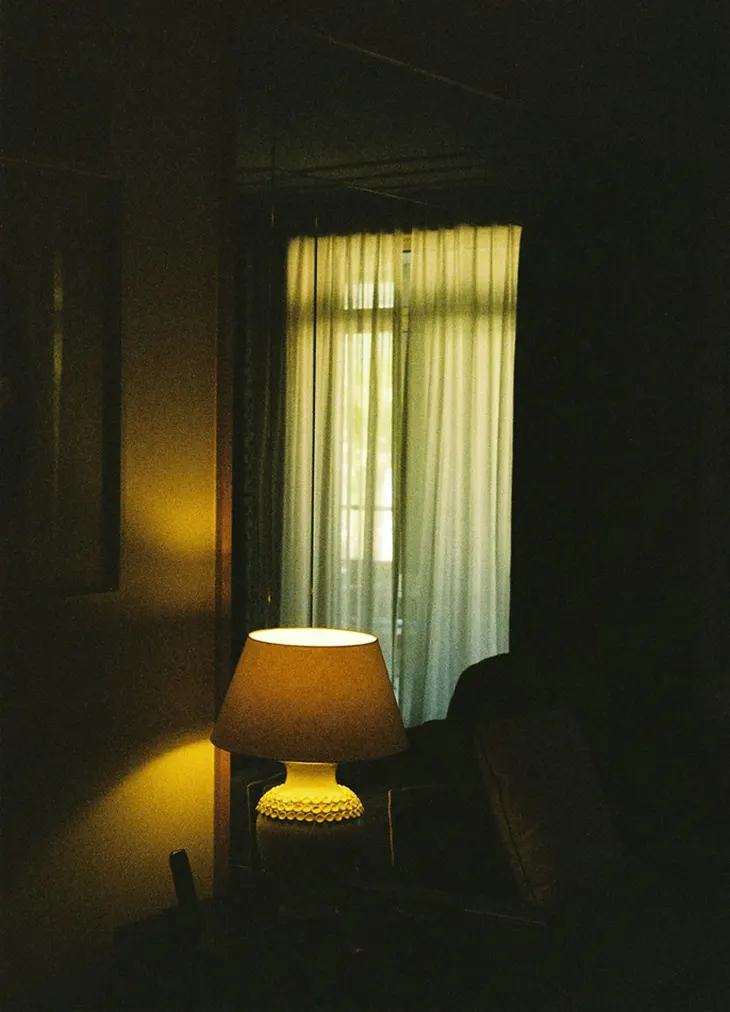

The new feminist apartment looks immaculate. It smells faintly of sandalwood and something labeled “skin musk.” There is a sculptural lamp in the corner. There is a bed with white linen sheets that appear perfectly unbothered. The bookshelf is populated by theory and objects found at local concept stores. The floor is polished concrete or matte-finished hardwood. The fridge is invisible, integrated into the cabinetry. There is no mess, no overflow, no clutter. There is taste. It is the curated language of a woman who appears to be doing well.

DORIC ORDER

This space is instantly recognizable. It circulates online in soft light. It performs autonomy. It signals that the woman who lives here has opted out of chaos, men, roommates, and anything else that might compromise her calm. It is aspirational without being loud, aesthetic without trying too hard. It offers control disguised as ease. You would be forgiven for thinking that this apartment is a victory. It certainly looks like one.

But the feminist apartment, like most architectural symbols of identity, is more complex than it wants to appear. Yes, it is free of outside interference. Yes, it reflects access, privacy, and a measure of economic comfort. It is often the result of years of personal and professional effort. But it is also a stage. It demands performance. It requires ongoing maintenance to uphold the illusion of control. It becomes another way of being watched, not by others, but by yourself.

What started as a space for freedom has become a pressure to prove that freedom looks a certain way. It should be serene. It should be beige. It should show no signs of emotional residue. The apartment may belong to one woman, but the audience is much larger. The interior becomes an alibi. It says, without speaking, I am in control. I am clean. I am contained.

There is a growing expectation that independence should be visually minimal. That the proof of success is absence. No visual noise. No sentimental display. No dishes left in the sink. No messy breakup energy. The feminist apartment, as we now understand it, has been cleared of debris. Emotion, too, gets stored out of sight.

What started as a space for freedom has become a pressure to prove that freedom looks a certain way.

This is not just a design trend. It is a cultural script. A clean apartment photographs well. It gives the impression of wholeness. Women in their thirties are expected to have taste, have opinions, have skincare routines, and have their emotional lives fully organized into digestible pieces. We no longer decorate for others. We decorate to prove that we do not need them. But this independence often ends up looking like erasure.We inherit design cues from Instagram, from friends who have entered the soft neutrality phase, from Pinterest boards and curated retail pop-ups. We are taught that luxury is neutral. That authenticity is raw wood and linen. That being unbothered looks like a shelf with two perfectly spaced ceramic bowls and a book of essays by someone who lives off the grid in Tuscany. The aesthetic has evolved, but the expectation remains the same. The space must reflect the woman. The woman must reflect the space. Nothing should be out of place.

A certain kind of feminism is now expressed through beige interiors and expensive taste. It is what happens when the politics of care are replaced by the politics of image. The apartment becomes a visual code. A soft protest. A way to say I am not part of the machine while still participating in the consumption that props it up. The feminist apartment is ethically scented. It is quiet. It is beautiful. It is, frequently, uninhabited.

There is often no sign that a body exists there. The bed is always made. The bathroom has no visible products. The kitchen contains no crumbs. The living room features a chair no one ever sits in. The woman who lives here drinks coffee from a handmade mug but does not appear to cook. If she does, it leaves no trace. The fridge is closed. The laundry is hidden. The cords are tucked away. The space is curated to suggest clarity. Whether or not it exists is another question.

Design is emotional labor. Especially for women. We are taught from childhood that our environments reflect our value. Mess is weakness. Control is power. To be put together is to be safe. A woman with a clean home cannot be falling apart. A woman with soft lighting and balanced proportions is fine. The apartment becomes armor. It tells the world not to ask questions.

Minimalism is not the absence of culture. It is a culture of absence.

And yet the questions remain. Who gets to live this way? Who has the time, money, and mental capacity to maintain this level of order? What is being performed? What is being avoided? And why do we continue to call it freedom when so much of it looks like quiet pressure?

I speak as someone who has tried to live in this image. I have declined to hang artwork because it didn’t match the mood. I have spent hours finding the right off-white paint. I have arranged my bookshelf to communicate fluency and restraint. I have thrown away gifts that clashed with my sense of aesthetic consistency. I have curated my home as if it were an extension of my taste profile, and at times, I have mistaken that for comfort.

There are moments when the silence of a clean apartment feels like safety. There are others when it feels like self-erasure. When there is nothing on the walls and no trace of memory, the space becomes a showroom. You start to wonder who you are performing for. You start to realize how many decisions were made to appear untouchable.

The feminist apartment is not a failure. It is the result of years of work, of separation from obligation, of a desire to feel sovereign in your own space. But that sovereignty often comes at the cost of intimacy. When there is nothing out of place, there is nothing to hold onto. No softness. No room to fall apart.

The feminist apartment is ethically scented, beautiful, and frequently uninhabited.

This is where design intersects with power. We are told that taste is neutral, that clean lines are universal. But they are not. They are the result of choices, of systems, of exclusions. Minimalism is not the absence of culture. It is a culture of absence. It rewards silence. It elevates detachment. It presents itself as effortless, but it requires constant vigilance.

There is also a class reality embedded in this aesthetic. The materials are expensive. The emptiness is maintained through labor, often unseen. The woman who lives in the feminist apartment may do the cleaning herself, but she may also outsource it. She may pay for peace. The calm is purchased. The order is designed. The freedom is conditional.

We should ask what we are giving up in the name of appearing in control. What kinds of domestic space allow for contradiction, for emotion, for mess that does not require shame. What happens when we let go of the performance of neutrality and embrace the discomfort of being visible?

To live alone as a woman is still a political act. To make that space beautiful is not a betrayal. But the beauty must serve the person, not the image. A feminist apartment should hold memory. It should allow for days when the laundry is not folded. It should reflect a life, not a curated absence.

This does not mean rejecting design. It means refusing to let aesthetics stand in for identity. It means recognizing that a chair is not a boundary, a muted palette is not an ideology, and a houseplant is not proof of self-awareness.

We are allowed to take up space, visually, emotionally, and through presence that extends beyond curated objects.

We deserve more than spaces that speak on our behalf. We deserve spaces that hold us without performance. Where the books are sometimes messy, the light is imperfect, the kitchen smells like something real. Where being alone does not mean having to prove that you are doing it correctly.

The feminist apartment is empty, but it doesn’t have to be. It can be full of contradiction, of comfort, of uneven rugs and chipped mugs and books left open on the floor. It can be beautiful without being controlled. It can be powerful without being cold.

We are allowed to take up space, visually, emotionally, and through presence that extends beyond curated objects. Through a life that reveals itself without needing to be perfected.

Katarina Doric is the Co-founder and Features Director of DSCENE Magazine. Educated as an architect, she has spent over a decade shaping the magazine’s cultural voice across fashion, design, art, and identity. Her writing moves between theory and intuition with rare control. Doric Order marks her first regular column, offering a new format for her ongoing interrogation of power, beauty, and control.