New York-based designer Zhihan Qian has a specific obsession: invisible frames. The systems we move through without noticing until we realize they’re shaping who gets access, who gets excluded, and who decides.

DESIGN

Few designers use their commercial work as research material for cultural critique. Qian does. By day, she creates brand identities for fashion and retail clients. By night and weekends, she makes books that dissect how designed systems encode power and exclusion. The approach is rare: treating professional practice not as separate from critical work, but as the evidence base for it.

From lonely objects to meme warfare

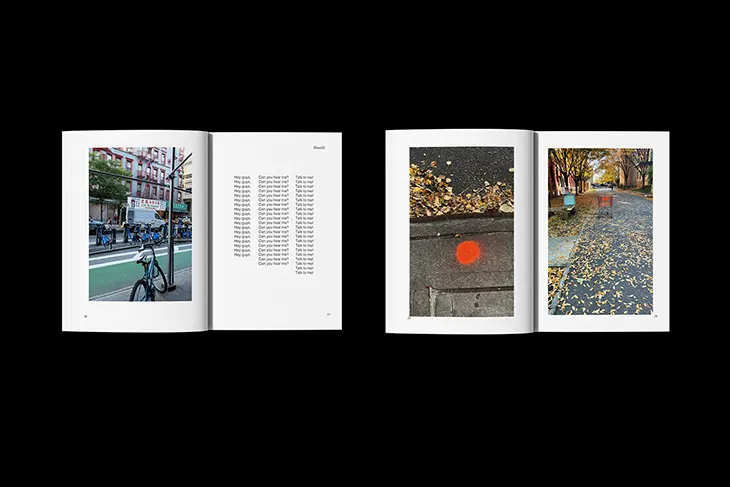

Qian’s breakout project was “Lonely NYC” (2023), a meditation on urban solitude through photographs of empty subway platforms, abandoned umbrellas, single gloves on seats. Everyday objects that somehow emanate human absence. In October 2024, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Thomas J. Watson Library acquired it for its permanent collection.

This is significant recognition. Watson Library is one of the world’s most comprehensive art research libraries, holding over 1 million volumes and serving an international community of scholars. The library maintains a rigorous artists’ publications collection focused on works with intrinsic art historical research value, collecting artists’ books, zines, and self-published works alongside rare exhibition catalogs and scholarly monographs. The acquisition placed Qian’s self-published work within the same research infrastructure that houses centuries of art historical scholarship.

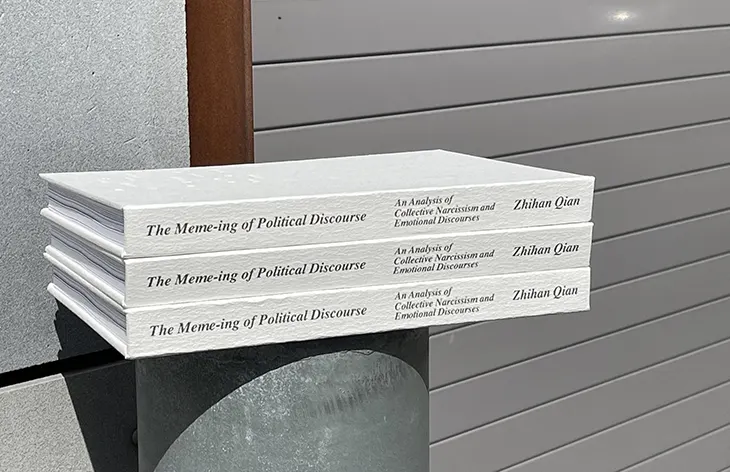

But “The Memeing of Political Discourse” (2023) operates at a completely different scale. Where “Lonely NYC” examined intimate urban solitude, this work dissects macro-level political propaganda. What makes Qian’s practice rare is this range: she analyzes a single glove on a subway seat and authoritarian meme warfare with equal rigor, treating both as designed systems that encode power.

Created at a moment when meme culture had fully weaponized itself, the project examines how collective narcissist groups use visual design to bypass rational discourse entirely. Her case study focused on fervent Trump supporters and their online ecosystems.

“I embedded myself in these online spaces and just observed,” Qian explains. “What I found wasn’t random trolling. It was a sophisticated visual system designed to communicate through pure emotional resonance. These groups don’t use memes to make arguments. They use them to trigger feelings so strong that argument becomes irrelevant.”

Decoding the aesthetics of authoritarianism

The project examines how specific design choices function as political technology. The deliberately crude typography, the clashing colors, the aggressive all-caps text, the distorted images. These aren’t accidents or incompetence. They’re calculated.

“The ‘bad’ design is the point,” Qian argues. “Professional polish signals elitism, establishment media, the ‘other.’ Amateur aesthetics signal authenticity, grassroots truth, us versus them. The ugliness isn’t a bug. It’s a feature that performs tribal identity.”

She analyzed hundreds of memes, identifying patterns in how collective narcissist groups escalate emotional intensity through visual means. Repetition that becomes hypnotic. Exaggeration that dissolves reality. Color and contrast that trigger fight-or-flight responses before conscious thought kicks in.

“What terrified me was realizing these visual strategies work on the same neural pathways as propaganda in any era,” she reflects. “But social media makes them instant, viral, algorithmically amplified. You’re not encountering one propaganda poster. You’re encountering thousands in a scroll.”

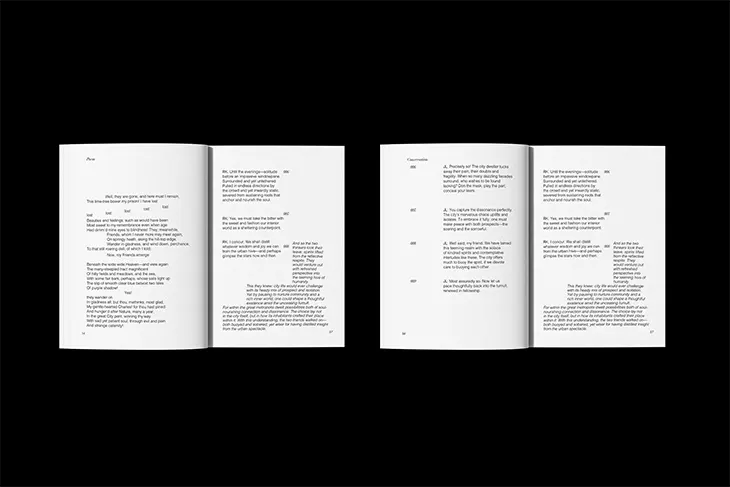

The project manifests as two forms. Large-format newspaper posters that mirror the visual chaos of the memes themselves. This is the visceral first response. Then a sober research book that provides analytical distance. The contrast is deliberate. The book sold out at multiple art book fairs and through independent retailers including Accent Sister Studio and MCBA.

“The posters are what it feels like to be bombarded by this stuff. The book is what it looks like when you step back and dissect how it actually works. I needed both to be honest about the experience and the analysis.”

An Emerging Force in Critical Design

Qian has built a practice that defies conventional categories. The MET acquisition. Features in Fonts in Use and OurCulture Magazine. Exhibitions at Brooklyn Art Book Fair, Detroit Art Book Fair, The Other Island at Pratt Institute. “The Memeing of Political Discourse” was selected for Pratt Institute’s thesis research curriculum, and Qian has been invited back to critique student work. This recognition signals its value as a teaching case for design as political analysis.

Her willingness to investigate vastly different scales marks her as operating in largely untapped territory. Urban loneliness. Digital authoritarianism. Colonial infrastructure in her latest “Lines of Control” on railroad politics in semi-colonial China. What makes this rare is the consistent methodology: using professional design fluency to decode how visual systems encode power.

“I’m interested in invisible architectures,” she says. “The systems that shape everything but get treated as neutral background. Subways. Algorithms. Meme templates. These are all designed, which means they encode specific interests and exclude specific people. Making that visible. That’s the work.”

This approach has value in multiple directions. The art world gains critical work grounded in professional expertise. The commercial sphere gains designers who understand persuasion as political technology. The design field gains a model for contributing to cultural discourse without abandoning economic viability.

For designers navigating platform capitalism and algorithmic manipulation, Qian’s methodology offers something necessary: staying critically engaged while maintaining the professional fluency to actually intervene in systems of power. Her work suggests design’s most important contribution isn’t making things look good. It’s making visible how things actually work.

Words by DSCENE Online Editor Maya Lane.

See more of Zhihan Qian’s work at archivezq.cargo.site and dreamlaborpress.com