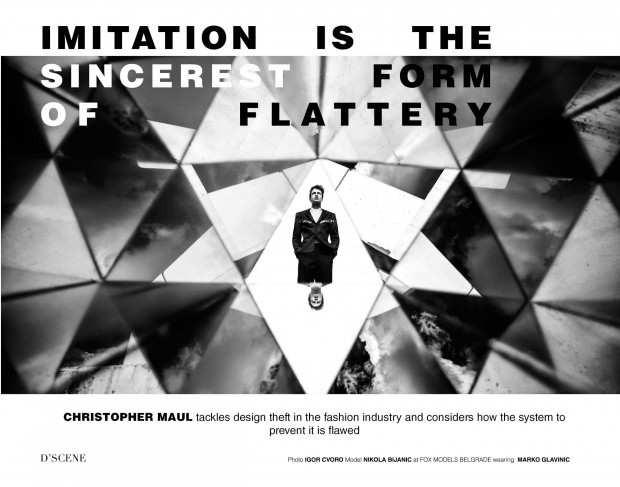

D’SCENE Magazine‘s Fashion Director CHRISTOPHER MAUL tackles design theft in the fashion industry and considers how the system to prevent it is flawed.

Coco Chanel made the point most precisely: “Those who create are rare; those who cannot are numerous. Therefore, the latter are stronger.”

In a creative industry it’s hard not to be referential. Designers constantly seek inspiration from their peers – it’s the norm. But when this admiration turns to copying, somebody needs to step in.

Design theft is rife. A grey area of law, designs are classified as ‘intellectual property’ due to their vague nature. Don’t let this fool you. Intangible maybe, but not invisible – design rights are valuable and worth protecting, particularly in the fashion world. If the global fashion industry was a country, it would rank 7th in global GDP: in the UK alone it is worth £37billion to the economy. With so much at stake, small wonder there’s a call for fierce defending of designs.

NEW D’SCENE MAGAZINE IS OUT NOW IN PRINT & DIGITAL

Style is subjective. It’s tricky assessing the extent a designer has drawn influence from another’s work. A broad brush approach won’t ever make the cut – set criteria can’t determine the value of creative additions added by the copyist. Each case needs to be considered on its own merit. You can’t please everyone. It’s not feasible to legislate for every case in one attempt because the options for copying are endless.

Everybody’s at it. In 2011 Christian Louboutin took Yves Saint Laurent (YSL) to court for copying its signature red-soled shoes, a case that gripped the fashion world. After appeal it was held that Louboutin’s red soles were entitled to protection, except when the shoe itself is red – allowing YSL to make and sell red-soled shoes. A true clash of fashion titans, the case was highly publicised and increased public awareness of design theft in the industry. It also made waves within the legal sphere. The fashion world was given special treatment – the law allowed the trademarking of a colour (albeit the use of one), which is not permitted in other industries.

If you can’t beat them, join them. Even Diane Von Furstenberg (DVF), famed designer and head of the Council of Fashion Designers of America, was judged to have copied the work of a more obscure designer. DVF was the driving force behind the Design Piracy Prohibition Act in the US and has sued Forever 21 and Target for replicating her designs. If this respected pioneer for the protection of clothing designs isn’t listening to what she preaches, that’s seriously depressing.

How can labels arm themselves for battle? Intellectual property rights (IPR) empower designers. They protect creations of the mind and are the gift of exclusivity for a brand. Like picking a team during a P.E lesson line-up, designers can choose who plays ball with their designs and can profit from doing so. If this right is infringed, the designer can take the copycats to court. Whether it’s the colour of a sole or the shape of a collar, if you can think it, you can own it.

It’s an uphill struggle for designers. The UK and French legal systems believe freedom of competition pervades IPRs and this principle is cited when curbing overprotective effects of IPRs. The law favours copyists – the default is to encourage competition and increase trade rather than allow monopolies on designs. IPRs either stem from registered designs (where a designer has sought to protect their work in advance) or from unregistered designs but legislation doesn’t make it easy to safeguard work by registration. Lots of red tape stands between a designer and the ownership rights they crave.

It’s not worth the effort to register designs.The speedy nature of the industry is an obstacle when attempts are made to legislate a system for IPR. The industry is caught in a vicious circle – the turnover of collections teamed with the slow litigation process results in a shabby utilisation rate of IPRs. It makes sense. Designers have more urgent priorities than shuffling thorough mountains of paperwork centred on a garment that will soon be ‘so last season’.

The system is futile. Once rights are granted from registration, the level of protection is incompatible with the needs of the industry. Considering seasons last only a few months, the five-year minimum protection period offered by registration systems is not appropriate for fashion designs. Time is money. Rather than wasting them on registration, designers should pour their efforts into new creations. Don’t dwell on the past, look to the future.

Unregistered designs are an option. Designers are under constant pressure to stay ahead of the curve and design registrations are low down in the priorities. All isn’t lost – they can rely on unregistered design rights. Though not as strong, EU unregistered designs have a shorter protection period of three years, which is more in line with the industry’s needs.

Perhaps this is unnecessary. The fashion world isn’t defenceless. Occasionally the law needs to intervene but before things get out of hand the industry can self-regulate. Reputations take years to develop but seconds to destroy – a bad review can spell disaster. “There is quite a bit of social media shaming especially on Twitter and Instagram,” said Cozette McCreery of Sibling. “Although OK, it’s possibly not the correct route to take but it has made the copyists take note.” Followers can spot a cheat and won’t shy from shouting about it. In such a small industry if one person knows, it’s soon common knowledge.

Cozette adds: “This is a difficult subject, especially now because of the instant access and freedom to Google both backstage and FOH [front of house]. You can find your work on a mood board in Milan or Paris directly after showing or on one of the high street brands. In the case of Nasir [Nasir Mazhar] last SS15 his work also appeared on someone else’s catwalk show in Milan. That really was incredible! And rather naive and stupid of the designer who did it.”

The culprits in question were sentenced. Tommaso Aquilano and Roberto Rimondi, the duo behind the label Fay, were found guilty of copying not by lawyers, but by fashion insiders. Nicole Felps of STYLE.COM didn’t mince her words when she reviewed their SS15 collection: “[They] were way too keenly influenced by Nasir Mazhar’s brand of streetwear. They employed a very similar font to the one the London designer uses for his underwear elastic logo, and otherwise borrowed heavily from his sporty vocabulary – see the similarities between their basketball shorts, hooded anoraks, and backpacks and those in Mazhar’s men’s and women’s collections.”

It didn’t stop there – the industry took to arms and a Twitter shaming frenzy stripped all credibility from the collection. The pair recognised the lucrative potential in London street wear but they should cash in on their own terms. Justice was served swiftly by the critics, and rightfully so.

There’s a time and a place. When copying crosses the line, the industry isn’t in a position to fix it. The law has a duty to act in the public’s interest. It’s a matter of protecting the consumer from being deceived – recreating an aesthetic is acceptable but counterfeiting is inexcusable. If trademarks are fiercely enforced, the brand’s reputation would be protected and customers won’t be misled. When a Cos shirt resembles a Gucci chemise the consumer knows they aren’t buying the real deal because there isn’t a Gucci logo. High street knock-offs aren’t fooling anyone but by being super accessible they make high-fashion pieces more desirable. A no-nonsense approach to regulating trademarks, with awarding damages for infringements, is essential to maintain integrity in the industry.

In reality, it’s incredibly tough to solve this fashionable conundrum. There’s no right answer but there are plenty of wrong ones. The industry’s contradicting interests and fast paced nature demand different needs of an IPR system. Let designers be. When someone’s nicked their patterns or nabbed their colour palette, let them act at their discretion. Each case is different – designers can balance the pros and cons before taking things to the next level. But sometimes you have to be cruel to be kind – if it’s a trademark issue, legal action is crucial to eradicate counterfeit goods that dupe buyers. Copying is inevitable but how we act upon it is still in question.

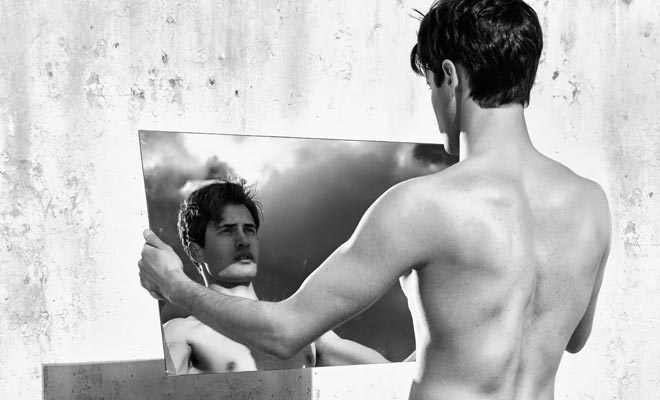

Images star model Nikola Bijanic represented by FOX Fashion Agency in Belgrade, Major Models in Milan, and M Management in Paris. In charge of the photography was Igor Cvoro, Nikola wears a suit by Marko Glavinic.

To keep up with our Fashion Director Christopher Maul follow @styleofmaul.