Guest Editor NATALIJA PAUNIC sits down with Artist ALEXANDRA BIRCKEN to talk about her latest show coincidentally titled 2020, the way the pandemic is influencing creatives, the EU and Bircken’s background in fashion.

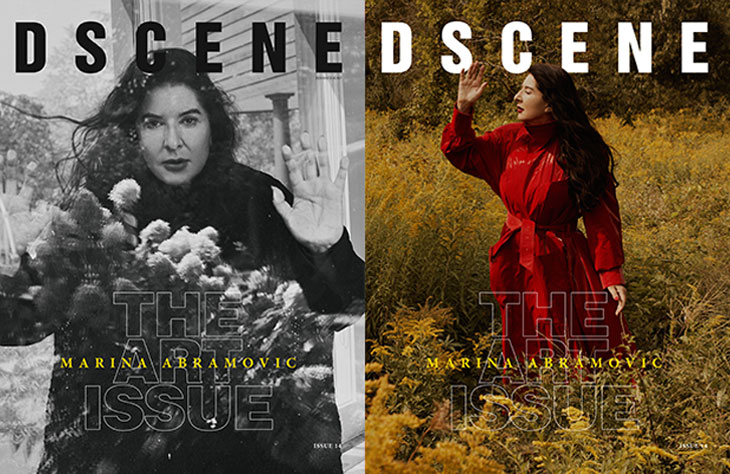

DSCENE 014 IN PRINT $12 OR DIGITAL $4.90

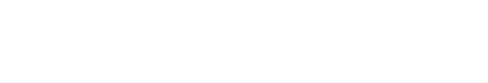

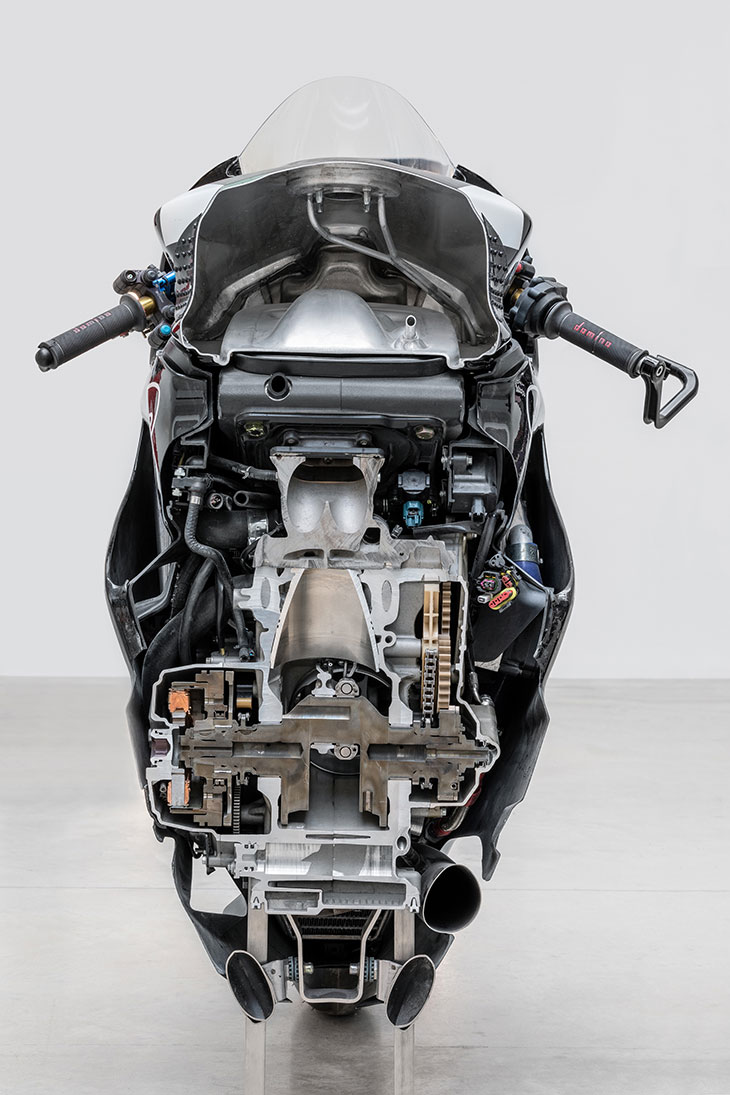

I had the pleasure to talk to Alexandra Bircken, whose work I started to admire greatly after having seen it at the Venice Biennale in 2019. There was something, as I say in the end of this interview, strangely prophetic about the second skin and the dissected, open, vulnerable body, of a motorbike, but nevertheless, that she has shown then, in regard to what we are all globally experiencing now, in 2020. I was happy to find out that she’d just opened a new show at Herald St. in London, called 2020 (funnily enough), so I started to inquire about it first.

Read more after the jump:

How did the opening go? Was there an official opening? Alexandra Bircken: People had to book slots, there were only six people allowed at the gallery at a time, so it was mostly one on one, one on three conversations among people. But it was very nice, people were super curious to see art again. You get really hungry to actually see physical art now, I guess. I was very happy that we were able to have an opening at all, considering the situation.

I saw some of the photos on your Instagram actually. The doctor! I can only presume what the exhibition’s about, considering what I saw, and the title – 2020. The original plan was to include some of the pieces that were shown last year at the Secession in Vienna, which was that motorcycle, the swing and two of these mirrors, called T(Raum), which is dream (Traum) and room (Raum) in German. This was a reference to Sigmund Freud and Vienna, the mirror and the dream, the reflection. I wanted to have this word play at that show. So, the London show was postponed, it was supposed to take place in May, and we were not sure when it would happen. During the lockdown, I couldn’t really work very well, like many artists. It really does eat into your creativity. The doctor that you mentioned, that piece was made in January. I had a surgery on my thyroid and kept the surgery gown. I also kept another surgical gown from my daughter, from the same hospital, and I had the idea to make something with it in the future. I decided to clad a whole figure in surgical gowns. And then corona happened. I was thinking of how to finish that piece and had this model boat, which I then put on the head of that figure, and then in sort of looked like this plague doctor. If you google it, you can see these plague doctors with these really curved masks, they look like beaks.

I do like to think of the ability of our own bodies, and just like with the motorbikes, disrupting the module, rather, dissecting them, makes them dysfunctional.

It has this sort of gothic look, right? Yeah exactly. So this piece, on the other side, has a prosthesis, and out of it comes a Christmas tree. It does play with the situation as it is, the crisis that we’re in. The show is tied to 2020 because of so many things coinciding. Many disparate yet very concerning events coming together in different parts of the world, so likewise, there are many bodies of work in this show that don’t really sit closely together, but they all refer to this year.

I feel like the title image, the Euro banknote gimmick, is also quite interesting in relation to the show happening in London, which is not part of the EU anymore. There’s a tacit sense of irony in that. It was intended that way. When I first came to England it was this open place, embracing other nations, cultures and just having this openness. In Germany it wasn’t like that – that was just when the wall fell. You had migrant workers, yes, but not this kind of diversity. Relating to that, the hands that you can see in the show belong to Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, who is also the one negotiating with, Boris Johnson, for example. She made the gesture that I stitched into this piece when she received the presidency. Somehow, this humble gesture is something that you can often see on saints, in religious representation. That piece stands in line with the other embroidery I made with Angela Merkel’s fingertips touching. Von der Leyen only did it at that moment, it was a sort of an ‘oh my God’ gesture. I think St Barbara has been depicted with this gesture, it definitely has to do with humility and humbleness. I think the touching gesture, in the end, stands apart from Ursula von der Leyen. It just happened to be her, and it happened to be all over German press. It’s not something she usually does, unlike Merkel, who does place her hands the way I depicted it quite often.

I think what Merkel does is a sort of a display of power, or rather a sign of it, because I see quite a few politicians repeating that same movement. That’s so interesting, especially if you’re just looking at their hands and not listening to what is being said or looking at their faces. Yeah, she usually does it when she’s waiting for something to end, or for someone else to finish talking. When she speaks, she doesn’t do it. In Germany everybody knows it’s her. The Italians associate it with someone from the Vatican, some English people thought it was Theresa May. Exactly – it has something to do with a position of power, authority. You’re with yourself and in yourself, your fingers touch, it’s a complete circuit. You’re not holding hands in your pockets, or crossing your arms. You allow your body to be this way, in a place of serenity.

I wasn’t even thinking about this in that way, the “coming full circle” of one’s own body. Making a connection with oneself on such a subtle level! Like when you do yoga. It’s not necessarily something she relates it to, of course, but it must be a gesture of reassuring.

Let’s talk about the body a bit more then – but moving on to your biking pieces. The reason I was so impressed with them was that, there was something super organic about them, even though they are completely mechanical. Even the suit – I find out now that it’s made of leather even though it verges between organic and artificial. There’s something very human about these sculptures, with no actual human presence or even human techniques when it comes to their handling. The super precise cuts, for example. Well the thing is that, it is organic, because the body shapes it. A body has been in it. Motorcycle suits, the way they’re cut, the point is to leave room for the body and prepare it for different situations, it allows room for you to move in it. It’s an armour basically, it’s not very comfortable, because of all these protectors and shields inside. It’s made of animal skin usually, because it protects your own skin much better. I find them super interesting because, as humans we protect our own body with the skin of another animal. I don’t even mean this in ethical terms. I am interested in the concept of second skin – it’s between us and the environment, the outside. People often have accidents in these suits, and when they do, the suits need to be cut open really quickly so that you can take them out, kind of like how you’d open a chocolate bar. I just started to get interested in them, what kind of marks the falls leave on the leather. Also the design, some drivers personalize them so that leaves a special mark as well. I ride bikes myself. I think they’re like modern horses.

If you don’t cater to the market and don’t make people feel attractive, you’ve got a problem. I felt very unfree and frustrated, and somehow started making these accessory pieces. This allowed me to be creative again.

I always think about horseback riding as well. Yeah, it’s definitely similar, how the saddle fits the body, it’s like a lid on a pot, you don’t have that in a car. In a car, you’re sitting on a sofa and you’re also in a cage. But with a motorcycle, you really feel the power, between your legs and under you, while not being cushioned. So at some point, I thought it would be interesting to cut through a bike and see its organs splash out. I wanted to see the inside of something that’s always been my interest. Of course, to cut it, you can’t cut it all at once. I work with various companies for this because it’s such a complex process. You mark the line and depending on the engine you need to choose the right position and the right techniques. The parts get taken apart and then they’re cut, depending on the material.

That’s strange cause it looks like a precise laser cut. Yes, because it’s so clean.

Cleanliness is not something I would normally associate with motorcycles. But, speaking of, would you say that this practice – biking itself – is an extension of our own bodies, our own abilities, a sort of our own power enhanced? Absolutely. I do like to think of the ability of our own bodies, and just like with the motorbikes, disrupting the module, rather, dissecting them, makes them dysfunctional. Cutting them actually renders them differently, it changes their value. The object or rather the body then becomes part of the art market, an entity of the art world. But it is also a painful situation, cutting it. That’s something I always think about.

So good that you’ve mentioned the art market. I know you have a background in fashion. Personally, I’ve always been interested in the relationship between fashion and art, not just in the sense of how they’re being created, but also with regards to the market. They feed into each other but they both depend on some sort of market. I feel like there are some specific things in which fashion is more free, ironically. You can do more without having to answer the question of “why”, avoiding a little bit of this critical observation in that sense, I think. On the other hand, I feel like fashion is something you can sell more easily even, being more approachable. Well – it’s cheaper. If you buy a jacket for 600 EUR, that would be just a collage in the art world [laughs]. I grew up with an interest in fashion, sewing, clothing, mostly due to my mom. Also, in the 80s and 90s, if you wanted to look different, as I did, you needed to make your own wardrobe. Take Madonna for example, then. For every album she made, she reinvented herself. This was the time – you and everyone else were constantly wondering, what was next? Who do you want to be? How do you shape yourself, what do you wear – that’s that second skin, the one that determined how you were being perceived. The figure wasn’t as important, it was what you put on it. That was the social background I grew up in, there was no other option for me.

I went to Central St Martins in London and really wanted to do this. However, when I finished my foundation course, people were asking me if I’m sure I don’t want to do art. The thing with fashion is that it only works on the body, it only refers to it. The body hasn’t changed exactly, you know? Stomach, arms, legs, head. It’s a bit of a limited situation. Also, the person that wears it needs to feel attractive. If you don’t cater to the market and don’t make people feel attractive, you’ve got a problem. I felt very unfree and frustrated, and somehow started making these accessory pieces. This allowed me to be creative again. Art came from these things that looked good on the body, but also on the wall. In 2004, I was approached by the BQ gallery in Berlin and that’s how it started. If that hadn’t happened, it would have probably been a much slower process, but I believe it would have happened anyway.

Would you say that the art market is not as limiting as the market in fashion? I think it’s much freer. It all starts with the money situation. If you’re a designer, you need to buy the fabric, need to have the studio, the machines, somebody to sew, to market it for you, and then if someone buys something from you, you need money upfront to create it, even before you’re paid. On the other hand, as an artist – how much does a canvas cost, paint, or a bag of plaster? You can always make great art with much less money.

Yeah, you can choose cheaper materials and formats definitely. Exactly, you don’t need to be Koons to make art, especially to just get into the art world. In art you can also say: I’m going to take some time off, focus on my work rather than the stability. You can also age in a different way. I mean of course there are limitations, depending who you work with, your background, gender… But it is still less limiting.

I liked it when the works didn’t have to do with the pandemic. When something was so directly or obviously related, it seemed cheap in a way. It was just a reaction, not that there’s anything necessarily wrong with it.

I guess as an artist, you can always even use that in a sense, the limitations. You can allow yourself to be critical. With fashion, that doesn’t always go down well. Also, see how women are portrayed in fashion. You still have that idealistic beauty idea, the thinness, this still hasn’t changed. There’s a few plus size models, it’s starting, but it’s still problematic. I think maybe this was the worst for me, I don’t fit into this.

Everything we talked about was pretty much related to the body, which makes sense of course, even with fashion. But what I wanted to mention in the end is skin itself – our first skin – an organ that protects us, the insides of us. And this leads me to the pandemic condition: even though we have this protective gear, masks, gloves, second skin and even skin itself, we still can be penetrated by this virus. Not just the virus itself, our mental wellbeing is being “penetrated” as well. Would you say this affected you creatively? To be honest, I think it’s too early to say. What I do notice is, in the streets, people actually avoid other bodies. This is something in our subconscious already. Other bodies have become a potential danger. But as for the pandemic itself, I can’t tell yet.

After I talked to some other artists about this, I recognised two types of behaviour. One group is obsessing over the pandemic, really talking about it a lot and having this hyper-productive drive with writing, interviews, texts and even artworks, materialised. And the other group is hitting pause. Maybe now is the time that these two are getting more into balance – some shows are opening spontaneously and in some interesting patches, like yours. Maybe we’re getting more adapted now. Yeah, it’s not as sensational anymore, now we live in it. I think we’re not binge-watching the news all the time anymore. I’ve travelled a bit during the pandemic. Now, being in London again, I’d say that everybody is experiencing it more or less in a similar way. This, together with the climate change, which is just as frightening actually. I think the rethinking that needs to happen preoccupies me a lot. I can’t say yet how this will shape my work. I bought a book about carnivals and these wooden masks in London. I found this so interesting – thinking about tribal or carnival masks, shielding yourself, but also decorating these objects. It’s happening now as well, it’s become a fashion thing. Decorating and wanting to say something with this layer that you put upon you. But this is just starting, I bought the book just last week.

I did make these metal hockey gloves for the Herald St show. They, for me, now have something to do with the situation even though they were made before. But the thing is that, so many things that had nothing to do with corona are seen in a new light – which is a danger, or it could be a good thing, I don’t know. They are now in a different context. I found it weird in the beginning when people kept up with these works made in the pandemic. I liked it when the works didn’t have to do with the pandemic. When something was so directly or obviously related, it seemed cheap in a way. It was just a reaction, not that there’s anything necessarily wrong with it.

I was thinking about this, actually. I thought it was redundant to make art so urgently in response to the pandemic, because I generally feel like art, contemporary art, has some prophetic quality to it. When you are making it, you are not just commenting on the world, you’re actually predicting a little bit. It might sound a bit too far off. But a comment is not usually offering any progress, it’s just looking at what happened.