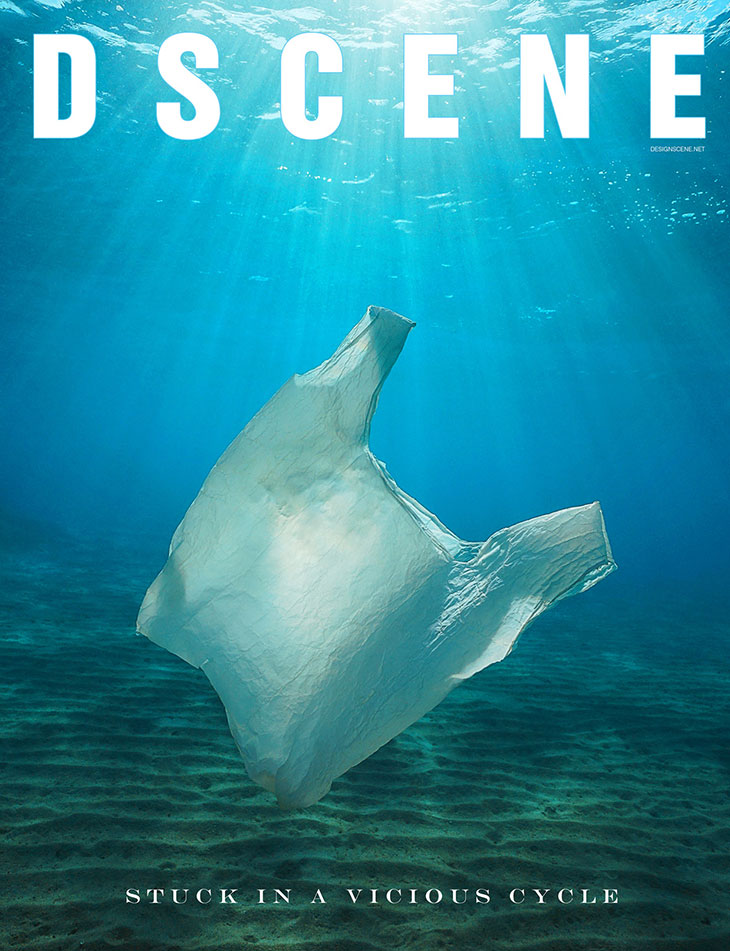

Blue is the warmest colour. It reminds us of the sky and its infinity. It reminds us of the rivers and oceans that nourish us and our environment. When seeking rest and recovery, most of us withdraw from everyday life by spending time in nature, oftentimes traveling to destinations surrounded by waters. You will find health resorts all over the world, nearby sea coasts and on top of the highest mountains, most of them attracting visitors with images of the clearest water one might imagine, while using slogans that suggest you’ll take a deep breath of the cleanest and freshest air of all times. Unfortunately, the sad reality is that neither the water you’ll dive into nor the air you’ll inhale are clean at all.

GET YOUR COPY IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

You and I will travel the world now. Together we will visit Italy and the Mediterranean Sea as well as Germany and the North Sea. We will visit Osu Beach in Accra, Ghana, and Rwanda’s capital Kigali. We will travel the Atlantic starting in North Carolina, USA, and head for the Antarctic. Crossing the Pacific Ocean we will visit Hawaii, China, and the Aral Sea in Central Asia. What we will do as well is travel time. We will look back at the past, examine the present situation, and see what the future holds for us.

RELATED: Read our 10 simple ways to help reduce your impact, and help in the fight against climate change.

Read more after the jump:

It was in the early 18th century, when the first machines to facilitate and accelerate the process of garment production were invented. By the end of the 19th century, fabric and garments were produced in large factories by underpaid workers, most of them women and children, who risked their lives on a daily basis during the 12 to 20 hours shifts. Microfibers and toxic dyes destroyed their lungs and skin. Furthermore, many factory buildings weren’t safe at all: a sad example of the risk that worker’s were put at, is the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire that erupted on March 25th,1911. 146 victims, most of them women, aged between 14 and 43 died this day.

Nonetheless, so-called ready-to-wear garment factories were booming soon, and by the early 20th century, stores offered low-priced clothes for everyone. Due to the increasing number of immigrants coming to the US as well as the garment mass production industry’s growth, first thrift shops were opened nationwide and became popular especially during the 1920s and 1930s. During the same decade, the first fully synthetic fiber, Nylon, was invented and soon used as a replacement for silk. In 1941 then, two British chemists produced the first known polyester fiber. While it is assumed that one million tons of synthetic materials (including plastic) were used during the 1950s, nowadays 300 million tons are produced – annually. While mass production of clothes is facilitated by technical achievements, we shouldn’t forget that nearly every garment we wear is hand-made by some underpaid worker in the Global South. The working routine of 19th century workers in the US is still a harsh reality for thousands of women and children in Asian, African, South American and South East European countries:

In 2011 AHA, the contractor reportedly responsible for 90% of Zara’s Brazilian production was found to have subcontracted work to a factory employing migrant workers from Bolivia and Peru in sweatshop conditions in Sao Paulo to make garments for the Spanish company. Workers were found to be working 16 to 19 hours a day with little time off and in debt to their traffickers. Fourteen of the workers were Bolivians and one was from Peru. One was 14 years old. – Cleanclothes.org

Water is a key component of several production processes related to the textile industry, especially when it comes to cotton and viscose. So, while it is less harmful for our environment to use garments made of cotton instead of synthetic fibers in regards to the possibilities of recycling and the material’s degradability after ending up in our environment, cotton production is still resulting in a massive water consumption in mostly arid regions. A famous example of the cotton production’s negative effects on our environment is the devastating shrinking of the Aral Sea in Central Asia. Starting in the 1960s, when the Aral Sea was the fourth largest lake in the world, the rivers supplying it with water were redirected to nearby cotton farms. Not only did former fishing villages disappear, but also did the region’s ecosystem change: more than 200 animal and plant species vanished. Nowadays, the Aral Sea is only 10 % of its former size, and satellite images show that what has once been a flourishing biotope is now a dreary deserted region. Rusted ship wrecks are a grim reminder that the area called Aralkum Desert today, was the harbor of Mo’ynok decades ago. Those, who still live in this region, became sick: fertilizers from nearby farmland and chemicals used in the factories contaminate the surrounding rivers, the remaining lake as well as the ground and therefore drinking water. Although locals and activists demand a change, there is little hope that the situation will improve any time soon. How long will it take until the last remains of water, the last remains of blue, will vanish, too?

Nowadays, the Aral Sea is only 10 % of its former size, and satellite images show that what has once been a flourishing biotope is now a dreary deserted region. Rusted ship wrecks are a grim reminder that the area called Aralkum Desert today, was the harbor of Mo’ynok decades ago.

Once a fabric is produced, it has to be transferred from its production country to the factories where the manufacturing process begins. It’s not uncommon that one item has traveled the world long before it ends up in your hometown’s mall. It is assumed that 95 % of goods are transported between Asia and Europe by sea routes. There are two options to transfer goods from one continent to the other: bypassing the African continent is the longer route, the shorter but more dangerous one means fording the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea as well as the Suez Canal and the Mediterranean Sea. At the same time, thousands of cargo ships cross the Pacific between Asia and the Americas. According to the United Nation’s International Maritime Organization, 90 % of the global trade is maritime trade.

Not only does shipping itself result in air and water pollution harming maritime wildlife. Surveys by the World Shipping Council showed that between 2011 and 2013 annually approximately 2,683 containers were lost at sea (including those lost due to catastrophic events). Although the number decreased between 2014 and 2017, WSC still assumes a yearly loss of approximately 1,390 containers. Between autumn 2018 and spring 2019 hundreds of shoes were found on beaches all over the world. First, they were noticed on Flores Island, a Portuguese Island of the Azores, in the middle of the Atlantic. As time passed, sneakers were found in South West England, Ireland, France and the Channel Islands, as well as on the shores of Bermuda Islands and the Bahamas. It is assumed that the shoes once were transported by the Maersk Shanghai, a vessel that was caught in a storm and lost roughly 75 containers in March 2018 when traveling with nearly 10,000 containers from Virginia to South Carolina. The dimensions and horrid impacts become evident in a statement by Dr. Curtis Ebbesmeyer published on BBC:

“A container can hold about 10,000 sneakers. So if you say 70 containers multiplied by 10,000, that gives you an upper limit [of 700,000 sneakers] that could be out there. It takes something like 30, 40, 50 years for the ocean to get rid of this stuff.”

Most of the shoes were linked to brands like Nike (who did not comment on the incident) as well as Triangle and Great Wolf Lodge (who confirmed that the found sneakers can be attributed to the vessel’s lost cargo). Not only do these items set free toxins, step by step they crumble into smaller pieces and become micro plastic. Several studies showed micro plastic is to be found in every single ocean and sea on this planet. According to a study by the National Oceanography Centre, up to 1.9 million pieces of plastic were discovered in one square meter of water of Italy’s west coast, and – as claimed by the NOC – even in depths of 3,000 ft “the highest level of micro plastic ever recorded on the sea floor” can be attributed to mostly textile microfibers. As stated by WWF in 2018, 7 % of the world’s micro plastic is to be found in the Mediterranean Sea – although it holds only one percent of the world’s water.

While yes, the masses of micro plastic in this region can be attributed to the many tourists traveling to Mediterranean countries, there are many (nearly) uninhabited places affected by the growing use of synthetic fabrics and materials as well. The Antarctic, for example. A survey by Greenpeace showed that microfibers as well as toxins such as PFC and PFAS (used mostly for outdoor textiles) polluted the region’s water and snow. You don’t have to wait for these kinds of synthetic microfibers to shed off a fabric after a piece of clothing gets thrown away. Every time you wash your synthetic outdoor jacket or sweatpants, roundabout 1,900 fibers (per washed item!) end up in the effluents of waste water and therefore in rivers and seas. In March 2020 scientists of Newcastle University discovered a new species of crustacean in the Mariana Trench at a depth of 6,500 meters. One of the animals had a micro plastic fiber in its hind gut. As a warning, the scientists named the new species Eurythenes plasticus.

700 marine species are threatened by plastic waste. You’d be able to find large plastic particles in the stomachs of approximately 18 % of tuna and swordfish.

While we don’t see the massive amounts of waste in areas that get cleaned on a regular basis by locals and activists, garbage piling up becomes even more visible in uninhabited regions. Between 2009 and 2018 a South African team of scientists visited the so-called Inaccessible Island, located in the South Atlantic somewhere between South Africa and Argentina. During one of their expeditions, the group collected nearly one tonne of plastic in a beach area of only 1 kilometer of length. In nine years the number of washed up objects increased by more than 50 %, from 3515 to 8084 items. Why are we still surprised when it turns out that animals’ intestines are full of plastic waste, as seen in April 2019, when a dead (and pregnant) Sperm Whale with 22 kilograms of plastic in its stomach was washed up on a beach in Porto Cervo, Sardinia, Italy? “It was like our usual life was there, but inside this stomach”, said Sardinian marine biologist Luca Bittau to The National Geographic. As claimed by WWF, 700 marine species are threatened by plastic waste. You’d be able to find large plastic particles in the stomachs of approximately 18 % of tuna and swordfish. Colin Janssen, professor of ecotoxicology at Ghent University, assumes that someone who eats 300 grams of mussels from the German North Sea coast probably consumes around 300 plastic particles at the same time. Dutch biologist Jan van Franeker studied nearly 1,300 fulmars and discovered massive amounts of plastic particles in 98 % of them. The studied seabirds found dead on several northern European coasts probably starved to death – although their stomachs were full.

In 2014, 50 million tons of textile fibers (including 64 % of all synthetic fibers used world wide) were produced in China. The growth of China’s textile economy also led to nearly two thirds of China’s rivers and seas being polluted due to chemicals used in terms of fabric manufacturing and clothing production processes. Oftentimes, companies dump toxic waste waters directly into coastal waters, as mentioned in the Greenpeace investigation “A Little Story about a Monstrous Mess” about two major Chinese companies producing children’s clothing. 85 clothing items were tested. More than 90 % of them contained toxic chemicals. In most cases, the amount of toxins polluting our waters remains invisible for us. But sometimes, what once was blue, turns blood red, as seen regularly in Bangladesh:

The odor rises off the polluted canal — behind the schoolhouse — where nearby factories dump their wastewater. Most of the factories are garment operations, textile mills and dyeing plants in the supply chain that exports clothing to Europe and the United States. Students can see what colors are in fashion by looking at the canal. ‘Sometimes it is red,’ said Tamanna Afrous, the school’s English teacher. ‘Or gray. (…) It depends on the colors they are using in the factories.’ (New York Times, Jim Yardley, 2013)

According to Science journal, more than 3,5 tons of synthetic substances are dumped into the Pacific yearly by several Asian countries. The thing is: most of these synthetic materials come from countries in the Global North. Therefore a tremendous amount of waste exported from Australia, the US or Canada to numerous South East Asian countries ends up in the Pacific. Recently, former Malaysian environment minister Yeo Bee Yin demanded a ban on waste imports and announced plans to send back 450 tons of waste to the countries of origin.

Oceanographer Jenna Jambeck claims that up to 13 million tons of plastic waste end up in our oceans every single year. According to Laurent Lebreton of The Ocean Clean Up, the US alone “contributes as much as 242 million pounds of plastic trash to the ocean” annually. Between 87,000 and 2,5 million tons of plastic in various forms and sizes are estimated to form a waste area in the middle of the Northern Pacific, called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Yes, you got this right: somewhere between the North American West Coast, the Islands of Hawaii and South East Asian shores is a patch of garbage as big as Western Europe. In the midst of these water currents are items dating back as far as to the 1950s. As if this wasn’t enough, there are even more garbage patches in the South Pacific, the Indian Ocean and the Atlantic. According to the Algalita Marine Research Foundation, the Southern Pacific Garbage Patch has a size of approximately 2.6 Million square meters – it is thus bigger than Algeria, the largest country on the African continent.

Between 87,000 and 2,5 million tons of plastic in various forms and sizes are estimated to form a waste area in the middle of the Northern Pacific, called the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. Somewhere between the North American West Coast, the Islands of Hawaii and South East Asian shores is a patch of garbage as big as Western Europe.

A way to act in a more sustainable way as a society is to produce less. Because seriously, there’s definitely no plausible explanation for any label to release 500 new designs weekly – which means more than 20,000 designs a year released solely by the Spanish company Zara. For us individuals, a solution to boycott this overproduction is to re-use and up-cycle especially clothes as often as possible. Of course, as someone who is part of a privileged society, we shouldn’t refrain from donating clothes to those who are in need. But we have to give up the idea that all donated clothes do good. Because unfortunately, the majority of donated garments does not necessarily help people in need, neither are they recyclable, but rather do they end up (who would have thought!) in our oceans.

Back in the 1970s, the first large amounts of clothes from the Global North arrived in Ghana. Because most of the garments were of good quality, locals associated the donations with wealthy people’s deaths, and therefore called them “Obroni Wawu” which translates to “dead white men’s clothes”. Nowadays, the quantity of garments being imported to African countries is so vast, that several African governments decided to counteract by increasing the taxation of imported second-hand goods, and therefore hope to strengthen the local textile industry. In Rwanda, approximately 22,000 people earn a living with donated garments, in Kenya the number of workers in the second-hand industry is as high as 65,000. Despite the fact that many African countries do have the resources to produce high-quality fabrics such as silk (Rwanda) or cotton (Tanzania), the major part of those materials is not used by local brands, but rather exported to Asian countries. There it is utilized to produce clothing for the Global North – just to be shipped back as a donation to African countries a few years later. We are stuck in a vicious cycle.

Nowadays, the quantity of garments being imported to African countries is so vast, that several African governments decided to counteract by increasing the taxation of imported second-hand goods, and therefore hope to strengthen the local textile industry.

Every week approximately 15 million garments arrive at Katamanto Market in Accra, Ghana, the largest second-hand market world wide. Most of them are new and unworn. And yet, according to The OR Foundation, 40 % of the second-hand items that flood Accra (means 6 million items per week) do not resell and therefore are sent to landfills or get dumped somewhere else. In cooperation with locals and activists The OR decided to clean Osu Beach, an area of Accras shores that is full of clothing previously meant to be sold on Katamanto Market, but was instead “buried in the sand or dumped directly into the water”. The major problem is that “Kantamanto generates more waste than the local waste management department can pick up”. According to the founders of The OR, there are two more ways how textile waste ends up on Accras beaches: not only is it buried in the sand or directly dumped into the ocean, a lot of clothing is also “dumped into the gutters where it absorbs all sorts of industrial and human excrement before being pushed into the sea”. Because one can find so many metal bands previously used to compress the bundles of clothes for transport, it is assumed that “whole bales are buried” on Osu Beach. The items are entangled, full of sand, and so heavy, that during the latest beach clean up two people had difficulties to drag a single shirt out of the sand. Depending on the material the items were made of, their previous shape and function are more or less recognizable. Sometimes the sand among the fibers became black over time. There are so many clothes in the nearby waters, that one oftentimes has to sweep them aside while diving into the water to take a swim.

Recent studies by researchers Deonie and Steve Allen show that waters polluted with micro plastic also eject microfibers and plastic into the atmosphere. According to Steve Allen, “winds can carry micro plastics far and wide, transporting them from European cities onto the supposedly pristine mountaintops of the French Pyrenees.” In Ghana, especially the area of Old Fadama in Accra is considered a highly toxic place due to the ongoing (oftentimes informal) burning of garments in the nearby dumpsites as well as in the Kpong landfill. The second-hand clothing trade in Ghana and especially the trading processes in Accra are extremely complex. But it is clear, that several social justice issues clash in this particular case. Without Africa’s history of colonial exploitation by Europe and the overproduction of goods for the Global North, there certainly wouldn’t be any of these environmental and societal problems in Accra. According to the founders of The OR, Liz Ricketts and Branson Skinner, “the Global North is relying on Ghana (and other nations) to take part in a waste management strategy necessitated by relentless overproduction and overconsumption. The question is whether justice is served by the position Ghana plays in this global system.”

When writing an article, journalists are faced with the question of what are the future reader’s expectations: What is the reader’s expectation in regards to the outcome of my text? What kind of feelings do I want to provoke in those who read the article? In most cases, us journalists try to remain hopeful and shed light on a certain topic’s positive aspects as well. And yes, there are numerous praiseworthy, important projects initiated by locals, activists, researchers and indigenous people in several countries of the Global South. Rwanda’s capital Kigali for example is one of the cleanest cities world wide due to several bills passed that made pollution of any kind punishable. Kenya aimed to ban PE plastic bags completely, which in 2017 resulted in a law that prohibits to make, use or sell PE bags in Kenya. Indigenous activists across Asia fight in various ways against the ongoing pollution of our waters, and several invented new ways of recycling, re-using or re-creating materials in a sustainable manner. Many women of colour and black women all over the world fight for justice and not only do they demand a change, but they also put a lot of energy in finding sustainable solutions for environmental issues. One of them is Kristal Ambrose, founder of the Bahamas Plastic Movement, who studied the Western Garbage Patch in 2012 and decided to take action. Since then, Ambrose spreads awareness for environmental issues especially amongst the youngest. Thanks to her, the Bahamian government lately created a task force to ban single-use plastic.

Everyone of us can change something about the current situation. We can make bigger or smaller changes in our everyday life, we can speak up about social justice issues at family gatherings and on social media, we can sign petitions and demand laws to get changed.

And yet, I honestly don’t want you to finish reading this text with positive feelings or the thought of you not being part of the problem, and therefore not feeling the need to be the change. Because we – the Global North – are all part of the problem. And all of us should be concerned about the effects of this perpetual over-consumption. But at the same time, we can do better. Everyone of us CAN change something about the current situation. We can make bigger or smaller changes in our everyday life, we can speak up about social justice issues at family gatherings and on social media, we can sign petitions and demand laws to get changed. We can also make sure that the framing and perception of absolutely non-sustainable actions as well as new sustainable solutions changes, and – as Ricketts and Skinner suggested – we should ask ourselves: “What knowledge/skills do we respect? What knowledge/skills do we take seriously?”

This whole environmental issue is about us from the Global North, and how we need to finally dismantle our own privileges. It is therefore especially a social justice issue about all the workers in the Global South being exploited, abused and put under risk for our societies constant need of new supply. When doing their research in Accra, The OR asked hundreds of retailers, if they wished for their children to work in the second-hand trade industry, too. None of them said yes. Because none of them wished their children to do the same emotionally and physically demanding work while being part of an exploitative market that lacks empathy, equality and social justice. There is no sustainable solution to clean waters without the elimination of what causes a sea of tears.

If you still think: “But what does this have to do with me?”, I can tell you one thing: Well, quite a lot. How many items obviously made of plastic can you name right off the bat when thinking back to your recent photoshoots? How many of these items contain non visible micro plastic? How many “sustainable” samples that you’ve used are probably made of a bio-degradable fabric while having plastic buttons sewed on them with polyester threads? How many of the cosmetics and clothes used during your shoot or runway show were previously packed in plastic bags or shipped in parcels and badges that were probably secured with polyester straps? How much of this would have been avoidable?

So, we’ve traveled all the 7 continents and over 20 countries together. And we could have traveled to way more places. Because environmental pollution has reached every part of our planet. And because there are many more activists worldwide demanding a drastic change. According to Ellen MacArthur Foundation, by 2050 plastic in the seas will out-weight fish. If we want blue to be the warmest colour, we need to plead for the waters to become free of waste, for the rivers to become free of toxins, for the lakes not to disappear:

“To build a different world we must recognize that it will not be a swift, smooth transformation. Revolutions are painful. The revolution of our time is bigger than an election, a product, or a moment of pause. It will take time to stop living as if we are limitless gods. Greed and waste are two ends of the same destructive path. But we can choose to recover.” (The OR)

Words by Lisa Jureczko – lisa-jureczko.com

Comments 1