Artist SEJLA KAMERIC sits down for DSCENE Magazine interview with Contributing Editor SLAVICA PESHIC to talk about the significance of a place of birth, her most prominent work and feminism.

The European art scene has become your second playground early on, but you keep returning to the Balkans. What does your origin mean for your work?

Origin is an obstacle. But it is the problems and the obstacles that make us look for solutions. That’s how we learn, discover, and grow. My biggest drive may be in having no sense of belonging. I am lonely by nature. I love the freedom that comes with loneliness, but I also suffer for it. To be born in the Balkans is not very lucky if you see yourself as a free person. It’s an obstacle. But there are places in the world with many more problems and misfortunes. So my struggle with the Balkans is not the worst thing. In fact, I have accepted it as a form of exercise—it keeps me fit. I didn’t want to run away and forget, so I come back to fight. We were not born in a place that offers the privilege of being relaxed.

You survived the siege of Sarajevo and were whiteness to heinous crimes that took place there, so the motif of war victims is present in your work. After many years of working with that subject, do you feel that you have redeemed the victims or that at least a basic human right to justice has been satisfied?

Unfortunately, there is no redemption or a basic human right to justice. The world is not a fair place. Art cannot fix things. Negation of crimes is a preparation for new crimes. Humans are an invasive species. We change slowly. Art helps, sometimes it educates, and sometimes it simply feeds the soul and the mind. One of the ways to survive a war is to refuse to be a victim. Resistance is a mental game. The mind is often the only weapon of defense.

The reason why we still haven’t accepted that a crime against women had been committed is that we don’t even understand what caused that persecution.

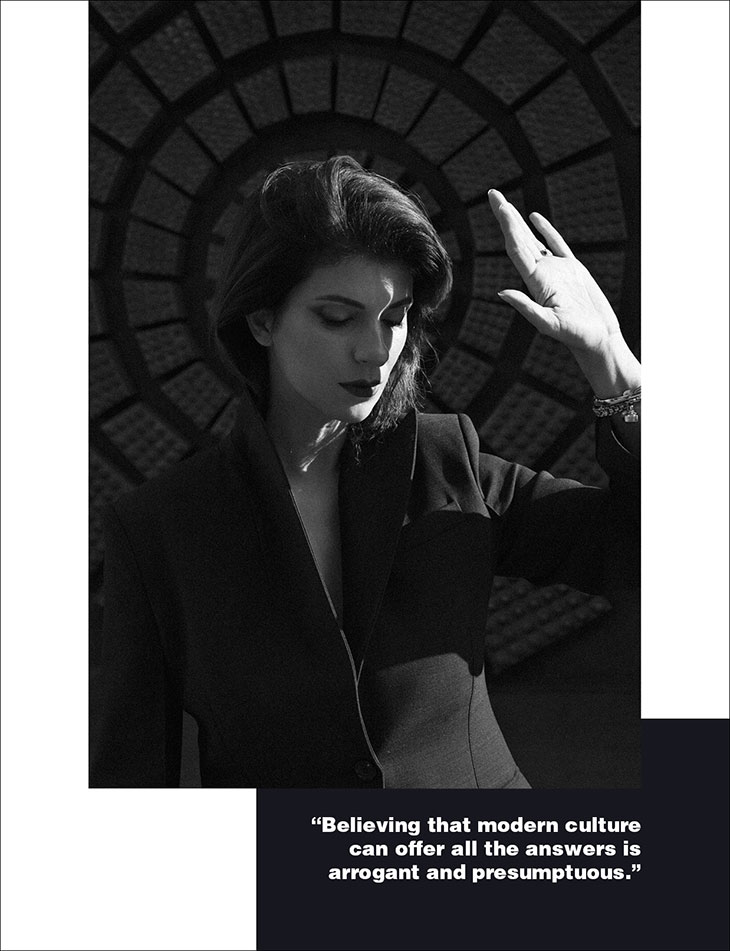

The work Bosnian Girl is an eerie testimony of the stereotypes about Bosnian girls written by the UN Dutch soldiers. What is a Bosnian girl truly like?

Through Bosnian Girl, I symbolically took on a role that was imposed on me by the war. It is a role of a victim, but it is also much more than that. It is a reflection of a viewer and a warning. Criminals need stereotypes and prejudice in order to hate, kill, rape, rage, spit, yell…the question that this work asks is why we accept prejudice and stereotypes so easily. How can we find them funny if they cause pain? They instigate a lack of understanding, and encourage hatred. We live in a permanent war where a woman’s body is used as territory. I am Bosnian Girl; I am the target, the victim, the territory to be dominated. But this work is not about me or about a Bosnian girl; it is about any girl or woman, anyone whose rights were denied. This work is from Bosnia, but it tells a universal story of prejudice, intolerance, and bigotry.

You mostly work with photography and video, placing explicit social context against intimate narratives. Has the social become intimately personal for you?

The way we feel and observe the world around us has to be intimate. What happens around us always ends up within us. From that depth, we give back and redefine the space we occupy. I believe that society consists of many intimacies. Our perspectives are individual, but they always have common elements. In my artistic practice, I always start from personal feelings and thoughts, but I am interested in precisely those mutual points of contact. Points that connect us even if we are on opposite sides.

At what level did that identification take place?

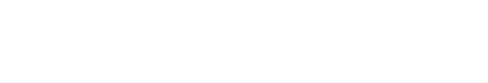

The world around us is very complex, and we will never be able to perceive it entirely. It exists despite us in an inconceivable time and space of the universe. Believing that modern culture can offer all the answers is arrogant and presumptuous. To survive, we must seek solutions. That is the intimate act that should be universal, social. I use it when I create art, but it is a principle that can be applied to everyday actions.

The exhibition and movie 1395 Days Without Red refer to the experience of movement and survival of Sarajevo’s inhabitants during the siege (1992-1996) when they were advised not to wear bright and vivid colors that would draw the snipers’ attention. How long can one truly manage without red?

That movie showed the choreography of survival. The mental resistance, which is manifested through movement and music. The protagonist, played by the Spanish actress Maribel Verdu, walks down the streets in the rhythm imposed by sniper bullets. This was the collective choreography of the besieged Sarajevo. Every intersection was exposed to sniper fire; every passerby was a target. Despite the danger, people were crossing intersections because life had to go on; people needed to get food and firewood, see the doctor, work, go to school…Maribel takes that road; she goes through those motions as if she were in the past, even though it is clear that the space around her is just a memory. Between intersections and running, she uses her unsettled breath to hum. This is the mental resistance that I’m talking about. In the movie, we recreated the Sarajevo Philharmonic Orchestra rehearsals that took place in the hallways of the RTV (Radio and Television) building during the war. It is difficult to imagine an orchestra getting together to rehearse and play in the middle of a war. This type of resistance to war is important to talk about. What is humane, what makes us better? Art is not just a noble act; it is a necessity and a corrective.

At the beginning of the siege of Sarajevo, Ozren Kebo wrote in his news column: “One is not advised to wear strong colors. Avoid red at all costs. The sniper is like a bull. Motley colors are also a bad choice. The sniper is a fool by definition, and every fool loves motley colors. Wear gray, brown, burgundy.”

During the Siege of Sarajevo, which lasted 1395 days, we wore red and were constantly aware that our clothes could turn red at any moment. Red was shivering inside us; it enveloped us—on our clothes and on the streets we were walking. Because of such a large presence of the color red, we decided to exclude the red color from the movie completely and thus take things to another extreme.

The pursuit of happiness seems like the only form of survival in your movie Happiness (Glück) with Milena Dravic and Olga Kolb. How do you pursue it?

The outline for the movie Glück comes from a quote from the book The Fiancés of Heaven by Mirko Kovac. I first read this book during the war in 1993. I was 16 at the time, searching for hope by repeating this quote: “Happiness is when you feel that what once you thought of as oppressive has now become the only meaning of life.” I still come back to that sentence that Leo Tolstoy wrote in his letter to B.N. Chicherin. There are things we cannot change. Acceptance is an essential part of our existence. Happiness exists in everything, even in the bad things. You asked me how I pursue happiness, but I will tell you where I find it—within me.

Your movie What Do I Know was awarded at the Zagreb Film Festival and Adana Film Festival. You won the Special Award at the 46th October Salon in Belgrade, the DAAD Artists-in Berlin Program Fellowship, and many more at the start of your career. Given the engagement of the topics you deal with, what do the awards mean to you in the context of supporting and affirming those topics?

When I received the European Cultural Foundation Award (ECF Princess Margriet Award for Culture) in 2010, it meant to me that Europe and the Netherlands accepted my political engagement and artistic work. And here I am—above all—referring to Bosnian Girl, which points out the role of the international community in war. However, the real reward to me is that the work was accepted by the women who were victims of violence in war and that the work is still relevant. Big awards are wonderful, they sound and feel great, but sometimes a kind word is the only award we need.

The way we feel and observe the world around us has to be intimate. What happens around us always ends up within us.

For those who don’t know the backstory, your work 30 Years After looks like a typical ad for a prestigious jewelry brand in a fashion magazine. In reality, it is about something very disturbing…

During the war in Bosnia, my mother exchanged her golden rings for food to ensure the survival of our family. My grandmother did the same thing during the Second World War. After the end of the Bosnian War, I started to obsessively buy golden rings with everything I earned. The need for security is often subconscious, it can blind us and be tragicomical. Privilege from wealth or for any other reason is dangerous. It often comes in white gloves and on high gloss pages. It is so important to be self-critical and understand how easy it is to slip. 30 Years After is a self-portrait of me at the age of 30. I’m 45 now, and I still buy gold.

What did art give you, and what did it take from you?

From early childhood, art was my only acceptable identity. I found a space in art where I can feel comfortable and safe. It took a lot of time and effort to learn to function in a system of imposed identities. That act of taking on roles and questioning them is a common theme in my work.

What was your growth as an artist like?

I studied art in high school, where I was not allowed to take the sculpting course because, by their standards, I was too weak. They told me that, as a “fragile woman,” I was ill-suited for that department and that I should pick a different one. I chose Graphic design, which I ultimately got a degree in, at the Academy of Fine Arts. While at the Academy, I started working as an art director at a marketing agency. I fled advertising as soon as I got the opportunity to exhibit as an artist. The flight might not have happened if it wasn’t for Dunja Blazevic, the legendary curator credited for many artists’ careers in Ex-Yugoslavia. She gently nudged me into making real art and realizing that neither graphic design nor advertising was what I had been interested in since childhood, the reason I always only wanted to become an artist. Looking back, I think it was a good thing that my education and initial career were in marketing and advertising and not in classical art forms. I learned how to manage myself, and it helped me communicate faster and more directly through the art I create.

You often use text in your work. Is that the influence of your previous career in advertising?

Because I am dyslexic and have dysgraphia, the text has always fascinated me as a task that I needed to master. I often use texts as found objects, like in my earlier work, EU/Others or Bosnian Girl. I apply the same principle in the new project I’m currently working on, which will premiere at the Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art next year. The base of the work are graffiti and various written messages created on the “Balkan route,” written by migrants, refugees, and people on the move who are fighting to get to the places where they’ll feel safe. Their pleas stay hidden because we are too busy staring at marketing messages and texts that only deal with deceit. I try to wrap those true cries in a way that they’ll resonate and reach the audience. Using artistic—and marketing—methods, I want them to become visible or at least a bit more visible. Text is a powerful tool; it can change the viewers’ perception.

Your work with textile is contextualized, and it also reflects the sociopolitical dimension of the world you live in. Why textile?

I have always been interested in the position of women, even when I didn’t understand which way to deal with it. I am also interested in fashion as a social phenomenon. But using textile in my work specifically came quite intuitively from crocheting. Doilies are women’s handicrafts. They arise from the need for creative expression. Their desire to decorate is misunderstood, devalued. They are marginalized, the same as the positions of those who created them. In a world where women were not allowed to express themselves creatively, their work “must” be useful, and their expression reduced. Throughout history, and even today, women were not allowed to go to school, to write, paint, build. Their role is to give birth, take care of children and men, cook, and clean. The only creative expression that women were allowed to do was weaving, knitting, embroidery, crocheting, and producing items that had a function. That’s how women invented decorations—the function became an excuse for creativity.

Ways in which feminism is fought for today?

Fighting for feminism is also in accepting ourselves and understanding the past. Centuries of brutal oppression are what shaped us. The past full of misogyny determined the difference between the positions of women and men today. The new series of work that I am creating is called Mother is a Bitch, and it deals with the history of the prosecution of women, restraining women’s emancipation, and dominance over women’s sexuality. In a series of photographs that are once again done in a manner of self-portraits, I use a broom as a prop and a symbol. Part of the research for this work was a poll. I kept asking the same question: “Why do witches have a broom, specifically?” Usually, no one knows the answer. The reason why we still haven’t accepted that a crime against women had been committed is that we don’t even understand what caused that persecution. And in order to connect the dots, we have to ask a series of questions. We should start with seemingly simple ones: Why do witches ride brooms? Why were they portrayed as young and naked or as old and ugly? Who were the witches, really? And, who still wants to believe in witches!?

Believing that modern culture can offer all the answers is arrogant and presumptuous.

Body as a medium and a means in art. Body as a boundary and body as boundless.

The female body has always been used and exploited, and it still is. It is liberating when a woman can use her body in the way she wants. Unfortunately, we are still far from that freedom. The doors keep opening, but they also keep closing. Advances are painfully slow. Often the only weapon and armor is that very body that gives life yet is considered controversial. Imagine a world where a female nipple has the same rights as the male nipple.

Do you prefer being in front of the camera or behind it?

When I was fourteen, I was scouted by a modeling agency and ended up in front of the camera as a model. My first magazine appearance in AS Magazine (which was published in Ex-Yugoslavia) was followed by a statement that I am more interested in being behind the camera than in front of it. Now, thirty years later, I can say that I find each of those positions equally important. I often produce, direct, and act in my work, and it makes me happy.

How analog is pain in a digital format?

I will reply with a quote: “Pain suffers no form.” I am interested in complex feelings. Through art, I research their dimensions; I try to discover new relations between feelings. Form often becomes a symbol, and causes and effects are shown as symbols.

Your work Dream House is an unusual nostalgia over the loss of a family home. After everything, all the travels, and moves, where in the world do you feel at home today?

They are different addresses. In Sarajevo, where my family is; in Istra, where I spend a lot of time and hope to spend even more time in the future; in Berlin, where I work and where I will always return; in New York that I love. But also in an imaginary space that I am yet to find.

Photographer IGOR CVORO – @igorcvoro

Fashion Director KATARINA DJORIC – @katarina.djoric

Makeup Artist MARKO NIKOLIC for Loreal Paris – @markofoxmakeup

Talent SEJLA KAMERIC – @sejlakameric

Photographer Assistant BORISLAV UTJESINOVIC – @crnilepotan

Interview by SLAVICA PESIC – @ballerinna

Sejla is wearing BOSS at Movem Fashion.

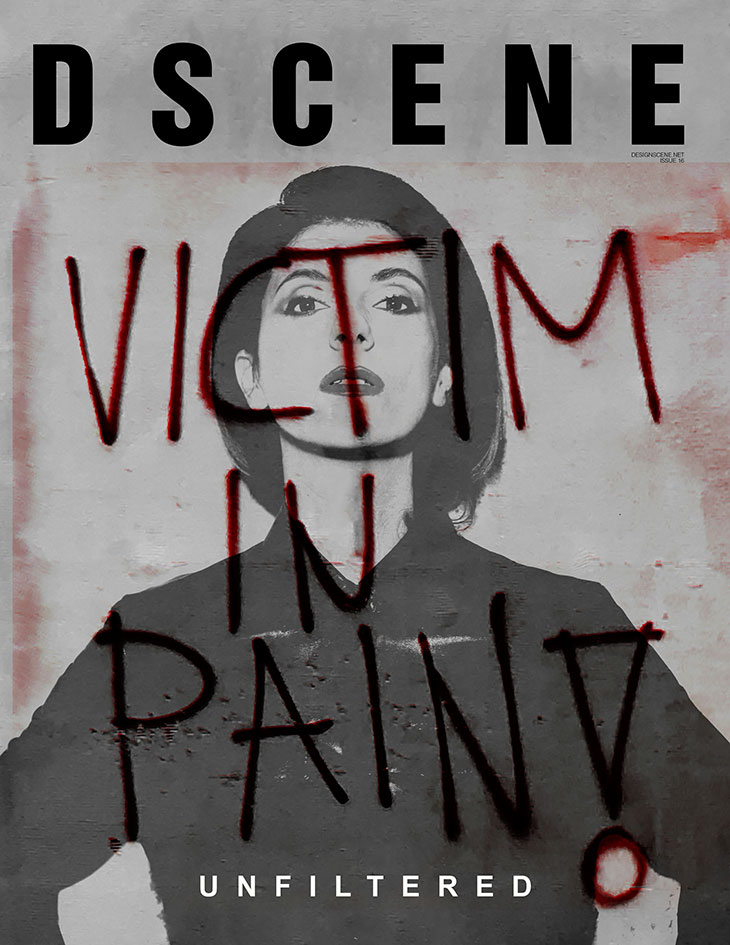

Interview published in DSCENE Issue 16 – get it now in print and digital.