Saša Tkačenko‘s exhibition “I Could Live In Hope” at Eugster II Belgrade gets its inspiration from a cathartic experience at a 2022 concert of the band LOW in Barcelona, which left a lasting impression on the artist during a time of global uncertainty. This moment of calm amidst the chaos of the pandemic, which Saša connected to the band, their music, and their performance, along with the passing of one of the band members soon after, strongly influenced the already present themes of decay and monumentality in his artistic practice and thought process. Through this exhibition, he created a space that translates these ideas and experiences into material form, and more importantly, into the relational empty space that all the pieces collectively create.

INTERVIEWS

In this exclusive interview for DSCENE Magazine with our Art Editor, Vuk Cuk, Saša discusses the process of setting up the exhibition, the ways in which the band’s name and work are contextualized, and all the symbolism that he interprets from it, touching on more universal themes such as memory, hope, decay, and emptiness.

You had a very specific process for setting up this exhibition. Can you share more about it? – I’m not sure how specific the process of setting up was, but it was definitely different. Setting up in a gallery usually involves physical labor, and its intensity varies depending on the complexity of the works I’m exhibiting. Often, during the creation process, I find that the initial idea and the production reality are in disharmony, so a lot of people with their knowledge and experience contribute to minimizing this disharmony during the realization of the works. This time, however, I consciously excluded any kind of potential collaboration. I wanted to treat the gallery as my studio, where I am essentially alone, and everything is happening for the first time. From the very start, I had a very precise idea, but I was completely open to letting it change freely until the last moment. It was similar to when I work in the studio, where the process of transposing the idea into reality is the only focus. The exhibition was built around a central piece on the front wall of the gallery, which I like to view as a kind of hybrid mural that, with its size, at first glance compensates for the large emptiness in the space, but in reality, it further and explicitly emphasizes it. It was very important to me to strip the communication through the works down to a minimum, to reduce them to signs, to just a few symbols that open up the potential to emphasize the emptiness that the viewer steps into to the maximum. I actually view the emptiness of the space as a kind of ephemeral sculpture that, although it has no physical form, is omnipresent and, above all, monumental.

The exhibition places the emptiness of the space in a delicate relationship with the exhibited pieces. What was your thought process behind this interplay? – It might sound paradoxical, but the emptiness is the only thing that matters. The works are like lonely buoys in an open sea, and when you notice them, you know you’re on the right path.

Why this band? – There are really many reasons, primarily because of the music they created and the way they performed it. Anyone who had the privilege of seeing them live knows what I’m talking about. The first and, as it turned out, the last time I saw them was in Barcelona in 2022, and it was a cathartic experience. I can understand that this might sound like a cliché to someone, but that moment of encounter was when many things came together. It was a specific period for the entire planet; the pandemic was still in its infancy, and closeness and encounters were very reduced. While we were all trying to lead a ‘normal’ life despite the great crisis, uncertainty sovereignly dominated our lives. And right there at their performance, I felt calm for the first time, as if everything had somehow slowed down for a moment and stopped being uncertain. Everything was finally alright despite the great and uncomfortable vacuum that filled the entire planet. At that moment, the omnipresent emptiness became okay and, in a way, my obsessive paradigm in thinking about the world and the society we live in. Not long after this concert, Mimi Parker passed away, and then I felt a genuine desire to materialize, through some form of my work, the monumental experience of that encounter with their music at the concert in Barcelona.

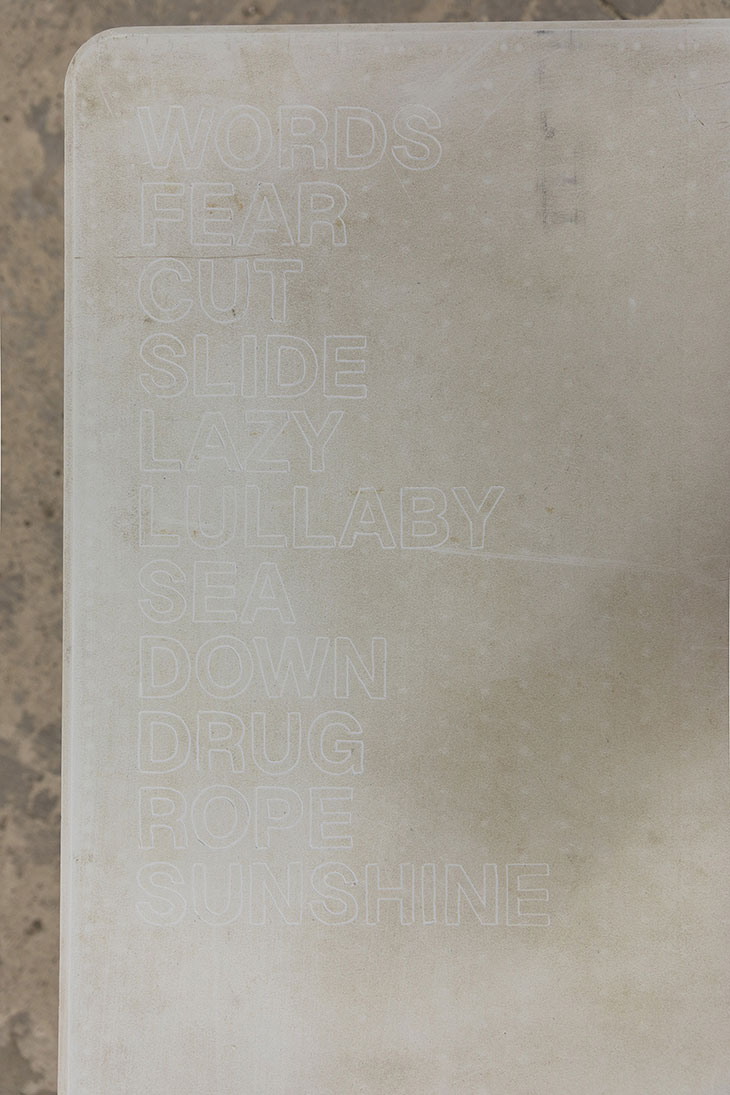

One of the works shows the band’s album tracklist carved into a table. Was your intention to give it a new context or produce new meaning with this intervention? – I would say both. What was interesting to me is that each song title is one word, and when these words are read in sequence out of the context of the album, they inevitably create a new meaning. Again, by engraving that sequence onto the surface of the table I found for this occasion, I tried to create a new context. A table, in a metaphorical sense, stands as a place of gathering where human presence is a desired thing. In this case, in the gallery space, on, and around the table, there are no traces of human gathering. The table functions as a kind of abandoned readymade.

The exhibition as a whole confronts us with an homage, commemorating a certain moment in culture, while also dealing with decay and oblivion. This seems to be a recurring theme in your work? – If you ask me what the connection in my works is, the first thing that comes to mind is ephemerality. The idea of transience is omnipresent when I think about my works. Again, if we consider ephemerality from the position of the conventional understanding of artistic work, it is something every artist wants to avoid. On the contrary, I see it as potential; I try to extract a new quality from ruins. Decay is an integral part of our lives, we know very well that not everything is always rosy. If I had to define myself in some sense, I think I am very close to the art of the Romantic period. Like them, I deeply believe that sincere emotion is the basis for understanding the world we live in.

The centerpiece appears to be the large “LOW” sign, made up of a neon light and two hand-painted letters. It also plays with these themes of monumentality and decay. How much of this exhibition reflects your need to process the passing of a band member and everything that came with it? – I’m glad you noticed that; it is in a way a monument or, better said, a proposal for a monument dedicated to decay. I think decay can be monumental, so the idea for a monument came naturally. The letter O, unlike L and W, glows in red neon, but this wasn’t out of a desire for a higher form of aesthetics. The neon further emphasizes the shape, which, besides being a letter, also has the numerical meaning of zero, which additionally points to and emphasizes erasure. The concert in Barcelona during that specific moment of the pandemic was a moment where these two things, monumentality and decay, overlapped. It was a moment after which I couldn’t stop thinking about the symbolism of the band’s name. It’s incredible how much is woven into just three letters, LOW. That’s why it’s complicated for me to talk about the other part of your question. It’s impossible to ignore Mimi Parker’s passing and the enormous emptiness that she left behind.

The exhibition feels very personal and intimate. How do you feel now that it has happened and is over? – Thank you for that observation; it means a lot to me that the exhibition leaves that impression. It’s strange, but I don’t see this as an end. Probably because these themes continue to fascinate me and occupy my thoughts. If you ask me if I feel emptiness after it’s over? My answer is no. My heart is full.

The title of the exhibition is “I Could Live In Hope.” How do you see hope in today’s society? – Hope seems to be the only thing left for us since I don’t see that we as a society are developing anything other than technological progress. If we exclude a few bright moments of social and societal progress and social emancipation, all this time since we became conscious beings and separated from animals, we haven’t really evolved much in terms of developing our emotions. We strive for a superhuman who is resistant to everything, including emotions, and without emotions, as the romantics say, there is no foundation for understanding the world we live in. I could live in hope, but…

LOW as in low energy