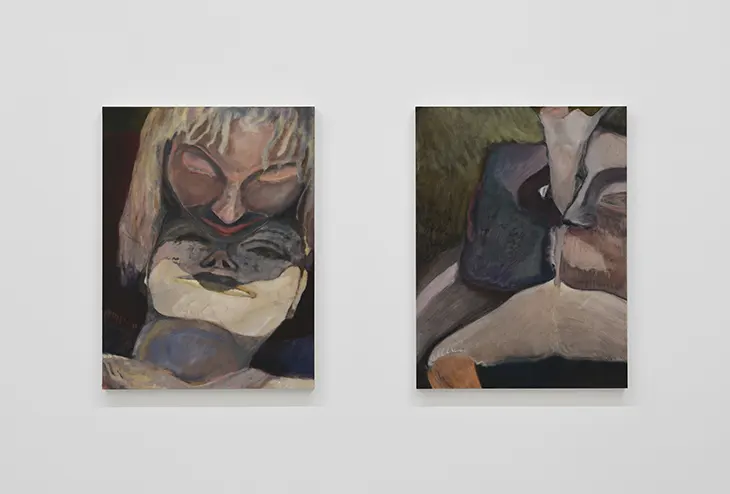

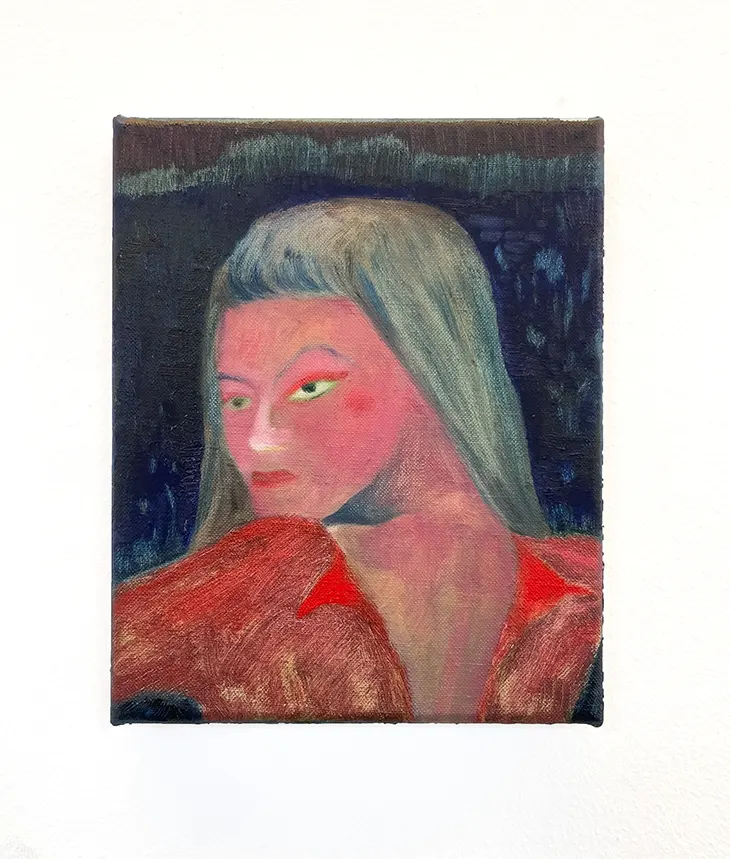

In her latest exhibition Waiting Room, painter Lexia Hachtmann presents a body of work suspended between emotional tension and quiet dislocation. Her canvases linger on moments that feel unresolved, where figures pause mid-thought, symbols flicker into abstraction, and time appears fractured. Referencing literature, cinema, and dreams, the artist constructs scenes that resist closure, instead offering a mood that is contemplative, ambiguous, and emotionally charged.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

In conversation with editor Anastasija Pavić for DSCENE, Hachtmann reflects on the role of ambiguity in her practice, the influence of myth and memory, and how narrative can unfold through absence as much as presence. Based between Berlin and London, the artist continues to develop a visual language that favors tension over clarity, inviting viewers into a world where meaning is never fixed, and always in flux.

Your exhibition Waiting Room at YveYANG takes its name from the liminal space in Twin Peaks. What drew you to that reference, and how does the idea of waiting resonate with your current work? – On Twin Peaks, the Waiting Room, a.k.a. the Red Room, exists outside of time. It is a metaphor as much as it is an actual space. I want the works in this show to encompass similar multiple realities and hover in a threshold that could tip either way. These paintings conjure a space that feels like an emotional recording of the world around us. In the Waiting Room, different rules apply, time and space exist on different planes. The viewer questions the rules of the fiction alongside the human condition. I like this. To me, a successful work speaks to past, present, and future at the same time, holding a certain secret and myth. I am drawn to painting because it is neither photography nor journalism, it plays by its own rules. Waiting Room also refers to a timbre of our current times in which we are sitting on the edge of our seats, not knowing what might happen next in a world of multiple crises. That’s the most literal interpretation, I suppose: waiting at the doctor’s office to be called into the back, not knowing if she’s going to say, “Hey, the tests came back and they are fine,” or “This is not looking good at all.”

I believe that ambiguity is inherently defiant because of the way it rejects easy readings and populist ideas.

Many of your figures seem caught in moments of ambiguity or pause. Do you see ambiguity itself as a form of quiet defiance? – I believe that ambiguity is inherently defiant because of the way it rejects easy readings and populist ideas. To me, painting’s role is not to illustrate, teach, or explain. It is rather the opposite—painting should create new questions instead of answering them. We live in a world that has become so complex on so many levels, and I feel that we need to be considered in the judgments that we make. We need to ask more and answer less. I make work by being curious and open to serendipity, not knowing exactly where I’m headed. I search, long, re-think, layer, and take a wrong turn. Then I turn around again.

Your paintings often feel like scenes from a suspended narrative, as if we’ve arrived just before or after something has happened. How do you approach storytelling, both within a single painting and across a full exhibition? – When I was young I wanted to be a writer, and when I grew up I became interested in film and theatre, which are both time-based mediums. I have no clue how I ended up becoming a painter. It definitely was not on my agenda for a long time, even when I started making art. Film, writing, and theatre remain my primary inspirations. This is not a conscious decision, but intuitive to how I frame and compose paint on the canvas. This sense of something that is about to happen, a tension, a teaser, a flirt, goes hand in hand with this. It reminds me of something Alfred Hitchcock said in his famous interviews with François Truffaut: be careful not to reveal the total shot right at the beginning of the movie. Keep it for the end. I learned much about painting in those interviews. I learned how to be aware of the “off-screen” and the “cadrage.” I try to leave the viewer to fill in the “pause,” the “unseen,” that opens up narrative notions to different readings and multiple perspectives, toward a stream of consciousness.

Gesture and gaze play a strong role in your work’s emotional tension. What kinds of relationships are you building between viewer and subject through those elements? – It’s two sides of the same coin. I want the work to feel intimate but never voyeuristic. It’s important to me that the subjects I depict are not helpless, even though they might be vulnerable, that they are never exposed, even though they might be naked, and that they are never bound by their gestures, but are portrayed within movement. I am not a fast painter, as I need to sit with the work and let it rest for a while so that I can return to it after some time, as a viewer, not as a painter. I need to make sure that this viewer and subject relationship is working the way I want it to.

Those sepias and shadowy purples feel central to your visual language. What speaks to you in that palette? – In recent years my palette has subdued. Still, I see myself very much guided by colour in my practice. As I learn more about it, my palette has become more subtle because the colours in the work are not fighting so much anymore on the canvas, not competing, but are rather supporting one another. Placing a yellow close to a purple in the right ratio will pronounce both colours. That colour exists only in relationship to another. I think the subdued palette and shadows in the work often pronounce their opposites, rendering light and colour in the work.

Painting should create new questions instead of answering them.

The yellow flowers appear like quiet witnesses in your paintings. Are they more than just a repeated motif to you? – “Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself,” goes the first line of Virginia Woolf’s famous novel, and this becomes part of another book written by Michael Cunningham, The Hours. He writes about the lives of three women (one of them Woolf), whose stories are spread out across different decades and places. Their stories intertwine through their commonalities with Mrs. Dalloway’s. This speaks to a generational lineage in which the yellow flower reappears in the lives of the three women, always to foreshadow something that is about to happen. It is an ambivalent symbol to me, acting both as a band of connection and a warning. It recurs in my work as a way to weave together and situate the pieces within an overarching narrative and universe.

You often turn to myth and memory rather than direct references to current events. Do you consider that a conscious detour from dominant cultural narratives? – If detour is defined as a way of getting to the same place by taking a different route, then yes. I don’t see a responsibility as a painter to reference current events directly. This would turn me more into a journalist of sorts. Being part of society, I see the artist as a sponge—someone who takes it all in and then digests it, combining it with everything inside: memory, lived experience, dreams, and personal interests. All of that is then churned, filtered, deconstructed, and reassembled subconsciously in a painting. Every lived experience is somewhere in the work. That is the beauty of painting. It is not illustration but a medium that can reference many narratives and emotions. And in its best case, it resonates with the present, the past, and the future simultaneously. It has the potential to do all that on just a few square centimetres of space. That is still so insane to me. In this way, I guess time is the detour that makes current narratives become memory and eventually turn into myths.

How much influence do artistic movements have on the way you think about your practice? – No more influence than anything else. I think they are just as important to me as the mundane, everyday things that move me: a good conversation, an interesting film.

Do you see slowness and subtlety in your work as a response to the pace and demands of the contemporary art world? – I believe that there is value in slowing down. Making a work takes me time—it challenges me. I have become better in recent years at knowing how to assess my energies and how to structure my time. I have become better at knowing what I can and cannot do. Saying no to things is an important part of being able to stay calm and productive. More is definitely not better.

I try to leave the viewer to fill in the ‘pause,’ the ‘unseen,’ that opens up narrative notions to different readings.

In the context of institutional pressures and market demands, how do you define artistic freedom for yourself? – I gauge my artistic freedom by the degree to which I am able to be present and curious in the moments I paint. My mind and body are the canvas. My inner world becomes the paint and the light in the studio around me. Institutional pressures and market demands should never enter the studio.

Lexia Hachtmann’s exhibition Waiting Room is on view at YveYANG Gallery, 12 Wooster Street, New York, NY 10013, from May 2 to July 5, 2025.

Originally published in DSCENE’s “Defiance” Issue: