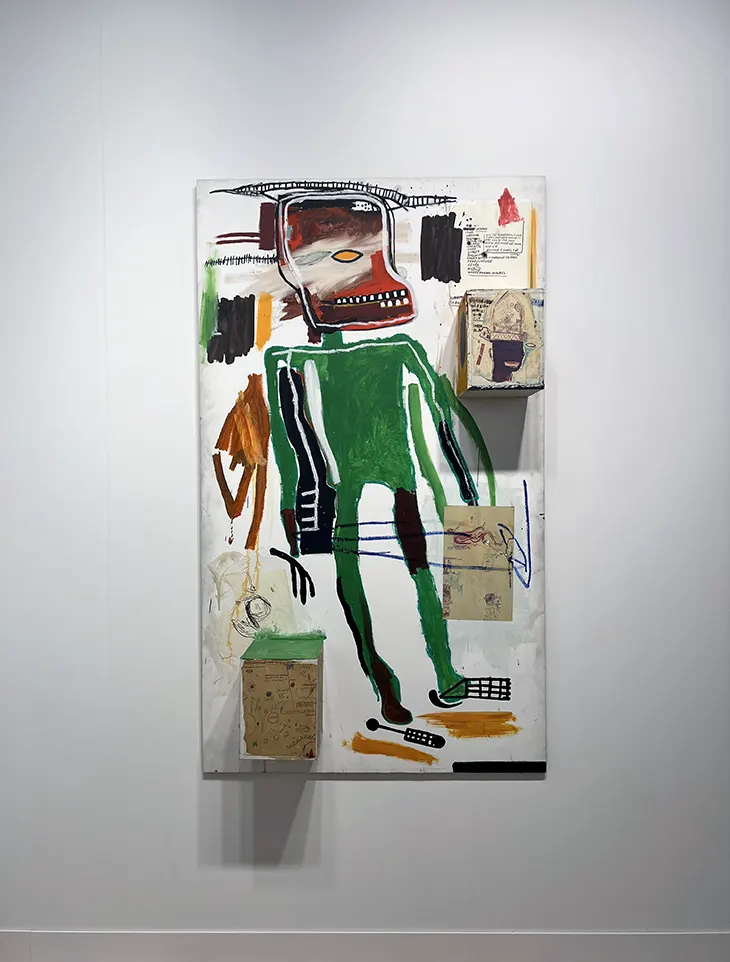

If 2020 brought the shock of a halted global economy, 2025 is revealing something quieter but equally disorienting: a slow, grinding contraction of the art market’s core systems. Global sales are down. Confidence among collectors is tepid. Mega-galleries are reconsidering their very purpose. And in a move that sent a tremor through the art world in early July, Tim Blum announced the closure of BLUM’s public gallery spaces in both Los Angeles and Tokyo, effectively ending a 30-year gallery legacy at the height of its influence.

ART

While calling 2025 the worst year for the art market may sound dramatic, a closer look shows it’s not far off. The downturn isn’t just about economic metrics; it’s also psychological. The sense of buoyancy and forward motion that once defined the industry has been replaced by something harder to quantify: hesitation, fatigue, and re-evaluation.

Global art sales dropped 12% in 2024, according to the annual UBS Art Basel report, bringing total market value to an estimated $57.5 billion. That’s the second consecutive year of contraction following a short-lived pandemic boom, and it’s particularly evident in the top tier. Works priced over $10 million saw a sharp 39% decline in sales, with many high-profile lots failing to sell at auction or being withdrawn altogether. The most recent edition of Art Basel Switzerland confirmed the shift: only one artwork priced above $10 million sold (Mid November Tunnel, 2006 by David Hockney) in the opening days, compared to four the previous year.

This stagnation at the top isn’t being offset by broader growth. While overall transaction volume is up, fueled by smaller, sub-$50,000 acquisitions, that volume doesn’t translate into confidence or sustainability. Dealers, auction houses, and advisors are adjusting expectations, and many have begun speaking quietly about a “reset” year.

Tim Blum’s decision to close his namesake galleries in Los Angeles and Tokyo underscores the exhaustion rippling through the art world. A key figure in bringing Japanese contemporary art to international prominence and championing artists like Yoshitomo Nara and Takashi Murakami, Blum announced that the gallery’s operations as a public space would cease, with a pivot toward a more flexible studio model.

“It was no longer fulfilling,” Blum told The Art Newspaper. “I didn’t want to maintain the system.” His remarks suggest that this isn’t a financial failure, it’s something deeper. A critique of the demands placed on galleries to feed an accelerating schedule of fairs, openings, dinners, and marketing cycles. In many ways, Blum’s decision marks a rejection of the very structure that once defined commercial success.

It’s easy to dismiss one gallery’s closure as a personal choice. But in context, it reflects a broader fatigue among mid- and large-tier galleries worldwide. The art world’s infrastructure, art fairs, global shipping, aggressive expansion, and relentless sales pressure, has become increasingly untenable. Blum, who once helped define that structure, may now be leading the way out of it.

The pressures aren’t limited to individual dealers. At recent auctions in New York and London, blue-chip lots once considered automatic wins passed without bids. Museums, still recovering from pandemic budget constraints, are absent or cautious at major fairs. Even collectors with deep pockets are showing restraint. The new norm is caution, not conquest.

Auction houses have adjusted by spotlighting more mid-tier offerings, embracing private sales, and downsizing staff in select departments. Fairs, meanwhile, are seeing fewer U.S. museum buyers and foundation curators traveling internationally. Many younger collectors, facing inflation and interest rate pressures, are looking toward digital channels, collectible design, or NFTs instead of blue-chip paintings.

Meanwhile, physical gallery attendance is soft. Many spaces are rethinking the traditional white-cube model in favor of hybrid programming, events, or digital outreach. As the market contracts, adaptability, not scale, is proving to be the survival trait.

The split in the art market is stark: while the high end is shrinking, the affordable segment is relatively stable. Works priced below $50,000 are moving. Platforms like Artsy and online auctions have helped maintain liquidity in this bracket, and younger artists continue to sell well through social media, direct channels, and local galleries.

But this isn’t enough to sustain the industry’s infrastructure as it’s currently built. Blue-chip dealers relying on multimillion-dollar sales, international shipping networks, and dozens of art fairs a year are being forced to recalibrate. Cost structures built for growth are colliding with a buyer base that’s increasingly cautious and values discretion over spectacle.

If 2025 has a theme in the art world, it may be sustainability, not in the ecological sense, but in the operational and emotional one. Collectors want fewer obligations, not more. Artists are reevaluating their relationships with galleries. Dealers are stepping off the treadmill. Blum’s pivot away from public gallery spaces toward a more personal, project-based approach may not be the last of its kind.

Interestingly, private sales are booming. Auction houses have quietly shifted focus to discreet, direct transactions between collectors, a model that avoids the optics of soft sales and public failures. Technology is also playing a stabilizing role: AI-backed tools are helping price artworks more accurately, digital provenance systems are growing, and data is helping to demystify market volatility.

The temptation to call 2025 the “worst year ever” for the art business is understandable, but not entirely accurate. Unlike 2008 or early 2020, this isn’t a collapse. It’s a slow unraveling of habits, pressures, and assumptions. In some ways, that’s more difficult to respond to. There’s no single moment of crisis, just a series of signs that the system no longer works for those inside it.

For a long time, the art world defined its success by visibility, velocity, and volume. That may no longer be enough. If Blum’s decision is any indication, the next era will be defined by selectivity, experimentation, and a return to slower, more deliberate models. The future won’t be fair-heavy or profit-first, it may be quieter, smaller, and more artist-driven.

And that’s not necessarily a bad thing.