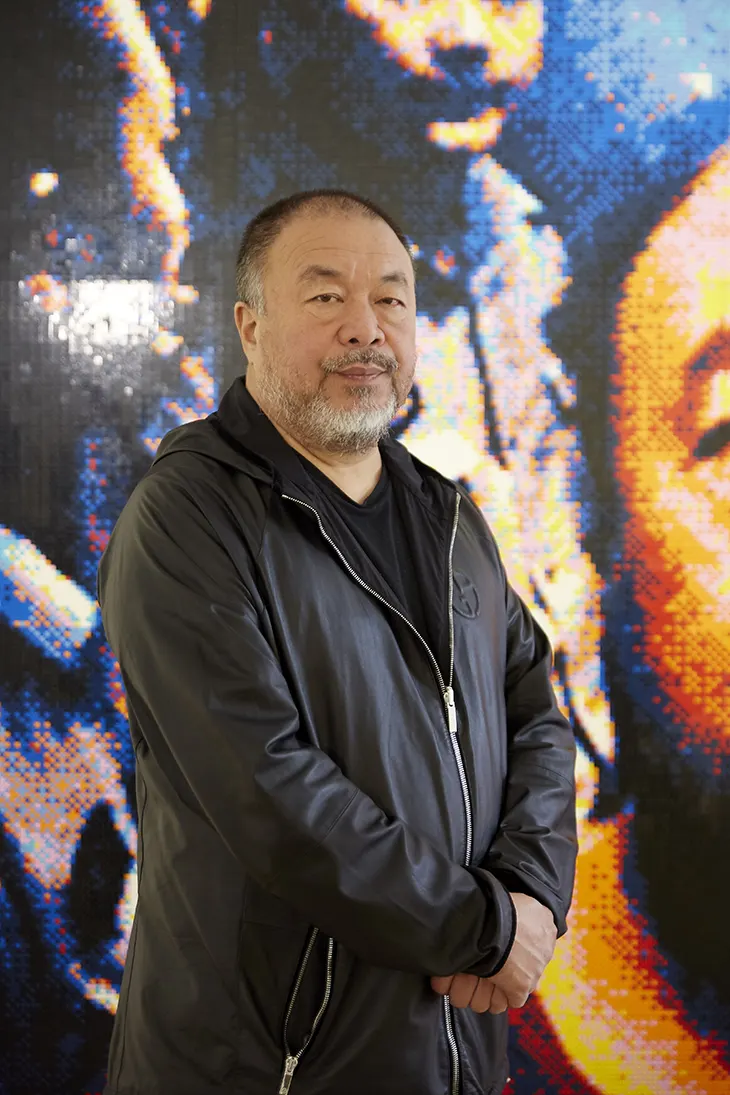

Ai Weiwei has never been interested in neutrality. For over four decades, the artist, documentarian, and activist has challenged political authority and cultural complacency with an unwavering commitment to truth. From smashing Han dynasty urns to constructing monumental installations out of debris, his work has become a visual and ideological reckoning with the systems that govern power, memory, and human life. Born in Beijing, and now living in exile, Ai has faced censorship, surveillance, and imprisonment, yet continues to create with sharp clarity and moral urgency. For him, art is not an escape from politics but a confrontation with it.

Ai’s practice is rooted in refusal: the refusal to forget, to conform, to remain silent. He has long interrogated the erasure of memory and the fragility of freedom through installations that reassemble the material ruins of trauma – scattered backpacks, demolished temples, cracked porcelain. His public artworks, often situated in highly politicized spaces, speak directly to institutions of power, demanding accountability while resisting co-optation. Whether responding to humanitarian crises, repressive regimes, or the complicity of global democracies, Ai’s work reminds us that art’s real force lies not in beauty, but in its capacity to bear witness, to disturb, and to endure.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

In this conversation with DSCENE editor Katarina Doric, Ai Weiwei reflects on the nature of defiance in a time of misinformation and global instability. From the ethics of spectatorship to the illusions of freedom, he discusses the burden of truth-telling under surveillance, the emotional cost of exile, and the challenges of making art that refuses to be absorbed by the very systems it critiques. He also speaks about Camouflage, his upcoming participatory installation that will be situated across from the United Nations at FDR Four Freedoms State Park this fall, and the tension between shelter and threat that defines our contemporary condition. Camouflage marks the launch of Art X Freedom, a new public art program that invites artists to create site-specific installations interrogating issues of social justice and freedom, commissioned by the Four Freedoms Park Conservancy.

Ai Weiwei defines defiance through clarity of purpose. He speaks of truth as something to uphold, not decorate, and of memory as a tool that cuts through distraction and fear. In a moment where forgetting has become habit, his insistence on remembering becomes a form of survival, asking each of us to consider where we stand, and why.

Your work continuously challenges authoritarian structures, often at great personal cost. What is the most effective form of defiance today – for the artist, the citizen, and the exile? – There is no such thing as “the most effective form of defiance.” There is only one true form of defiance: the protection of the value of life—an act of sustaining that value. In any circumstance, resistance without a cost is essentially not resistance. All defiance is measured by the price people pay.

You have lived under surveillance, imprisonment, and censorship. How do those conditions alter one’s relationship to truth, memory, and the construction of public narrative? – I have lived under surveillance, imprisonment, and censorship. This is also a fundamental attribute of existence—one often misunderstood as something unique to authoritarian regimes. In fact, such conditions are universal. As long as authority and interest groups exist, so too will censorship. People often consciously or unconsciously acknowledge or accept distorted truths, memories, and historical narratives in silence. This silent acceptance itself, paradoxically, affirms the actions of those in power as they seek to sustain their rule.

There is only one true form of defiance: the protection of the value of life—an act of sustaining that value.

Much of your work grapples with state violence and historical erasure. How do you approach the question of artistic responsibility when dealing with trauma that is ongoing, not historical? – Art that cannot provide individual thought or an independent sense of responsibility in confronting reality lacks a reason to exist. I believe art cannot avoid engaging with state violence and historical erasure, because the value and quality of life—whether in aesthetics or ethics—demand direct engagement with the issues of society.

View this post on Instagram

You often use archival materials (photographs, objects, debris) in your installations. What role do physical traces play in your resistance to forgetting, and how do you curate what deserves to be remembered? – The photographs, objects, and debris in my installations serve as evidence. I’ve said before: you cannot accuse corruption or evil without concrete proof. With evidence, the process of resistance becomes visible; without it, words are empty. Any archival material—be it a documentary, a series of photos, or a story—only gains meaning when it preserves historical continuity. Then, it can serve as a compass to help ourselves and others understand the truth.

In our time, protest is often aestheticized, and outrage is rapidly commodified. How do you navigate the danger of your work being absorbed by the very systems it seeks to criticize? – We cannot prevent this kind of appropriation or misuse. The only way to respond is to persistently fight back—to ensure that criticism continues and sustains its consistency. Only through this can it become convincing. In this way, the artwork cannot be absorbed because the system cannot swallow it.

Exile, voluntary or forced, has shaped your life and practice. What has it taught you about statelessness, belonging, and the limits of freedom? – Exile, at its core, is a detachment from familiarity and an entry into the unfamiliar—even into exclusion. The loneliness, alienation, and sense of being cast out are often damaging to life. Yet for an artist, these conditions can sharpen awareness. They deepen the understanding of why art exists and help reveal new perspectives and ways of thinking.

How do you see the relationship between silence and resistance? When does refusal to speak become more powerful than speech? – Silence itself can be a form of resistance. When power desperately seeks your approval, your silence becomes powerful. When power ignores your existence, silence is powerless. In most situations, silence is a path toward death, because it avoids the essential attribute of resisting death. In today’s chaotic world, silence may offer some degree of protection, but it cannot be more powerful than language—because language is a measure of expressing life. Silence only becomes truly powerful when it is a refusal in the deepest sense: when people ask you to speak and you decline, or when they ask for your submission and you resist—that is when silence carries real weight.

Camouflage reimagines a sanctuary using netting associated with war, shelter, and concealment. How do you see this duality, protection and threat, reflecting the current global condition of freedom? – Camouflage holds dual meanings. On one hand, it offers protection for life; on the other, it confuses the opponent. Camouflage is not only a refuge—it’s also a strategy of attack. In today’s world, where protection and threat coexist, camouflage belongs not just to warfare but also to the ethical fabric of society and the deceptive realities of so-called peace, freedom, and democracy.

Silence only becomes truly powerful when it is a refusal in the deepest sense: when people ask you to speak and you decline, or when they ask for your submission and you resist—that is when silence carries real weight.

The installation invites the public to contribute their own reflections on freedom. Why was it important to incorporate a participatory element, and how do you think this shared authorship challenges traditional notions of monumentality? – Public art—or any artwork created in a public space—is inherently a statement. At the same time, it creates a space that encourages thought and debate. This participatory possibility dissolves the monumentality of the work and instead challenges the value and purpose of all forms of existence.

Do you believe that spectators have ethical responsibilities, or is it enough to witness? – Everyone who has the ability to feel and to express also has ethical responsibilities. “Enough to witness” is, in most cases, a way of “seeing without truly seeing”—a passive act that enables evil to persist and even allows one to become complicit in it.

Situated across from the United Nations and embedded within a presidential memorial, Camouflage engages in direct spatial dialogue with institutional power. What responsibility does public art have when placed in such politically charged locations? – A public artwork’s very presence challenges the discourse of public space. It brings about a kind of politicization, or extends the debate through the lens of art. The values we hold today are entering a period of deep challenge and redefinition.

The quote “For some people, war is war, for others, war is the dear mother” underscores the asymmetry of suffering and profit in conflict. How do you think art can expose those imbalances and hold people, or systems, accountable? – Wars are cruel because they take lives under the guise of noble causes. Yet behind every war lie profits and profiteers—this is clear. Without profit, wars would not exist. War is simply an extension of politics. In this context, the artist’s role is to highlight the value of life and the possibility of peace. Without these, there would be no art to speak of.

How do you hope this project will shape the future of public art as a tool for dissent, testimony, and democratic engagement? – Any project merely offers a possibility or a hypothesis. It unfolds in the process of becoming—and that process is often complex and contradictory.

So-called artists, if they possess a moral sense or even the most basic human wish for healthy coexistence, should stand up and speak. Far too few do. That in itself speaks to the brutality of our reality.

In the context of global conflict, disinformation, and forced migration, how can artists contribute to building alternative futures rather than simply addressing the present? – We live in an immensely complex era—not just because of global conflict or the challenges of technology and artificial intelligence. Simultaneously, many people suffer due to war, poverty, and climate change. So-called artists, if they possess a moral sense or even the most basic human wish for healthy coexistence, should stand up and speak. Far too few do. That in itself speaks to the brutality of our reality.

What do you want the next generation of artists and citizens to learn from your persistent defiance and commitment to truth? – I hope the next generation of artists will, through their efforts, discover a renewed definition of life’s value. Every generation of artists must redefine what the value of life means.

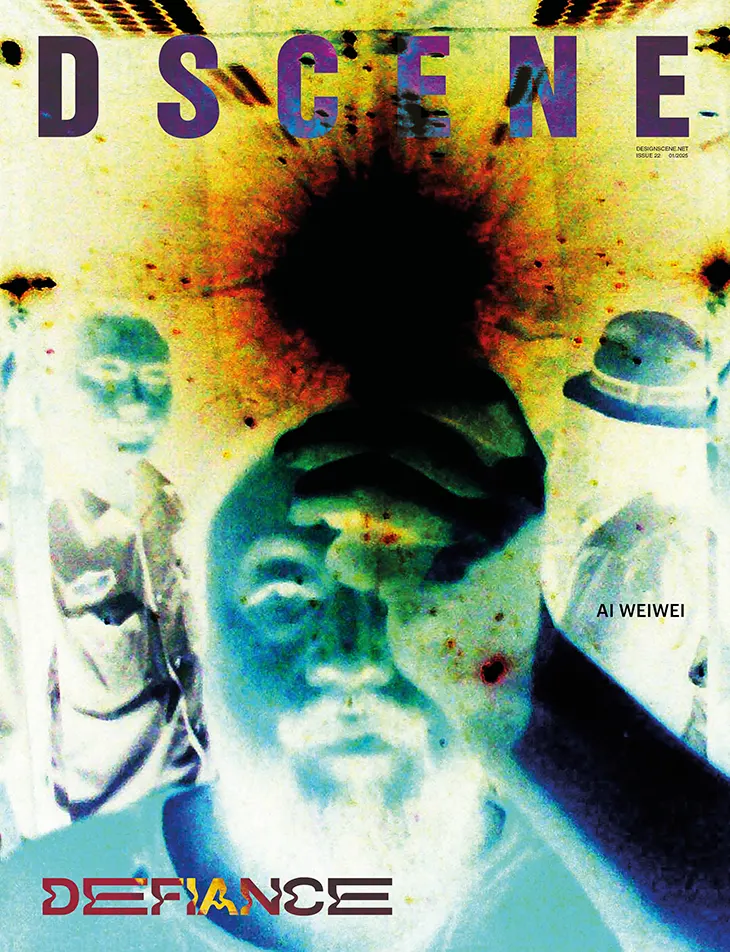

Tell us about your DSCENE cover design. – The content of this issue and the responses I gave to the interview questions are deeply connected to the cover design. The image has become an iconic symbol of our time: an artist using a mobile phone to directly challenge and confront authoritarianism and power. The conflict it represents is unmistakable. Der Spiegel even referred to it as the “Mobile Phone Revolution.” While this might be an exaggeration, it suggests that, much like Da Vinci or Picasso’s Guernica, this image defines an era from a unique perspective. The image itself is compelling, particularly in its interplay of light from the flashlight and the mirrored reflection of both myself and my musician friend, Zuoxiao Zuzhou. It is a spontaneous moment that has rapidly spread across media. For these reasons, I believe it is incredibly worthwhile to feature this image again.