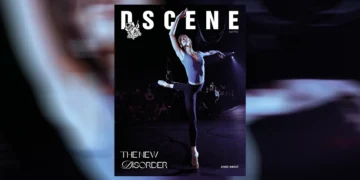

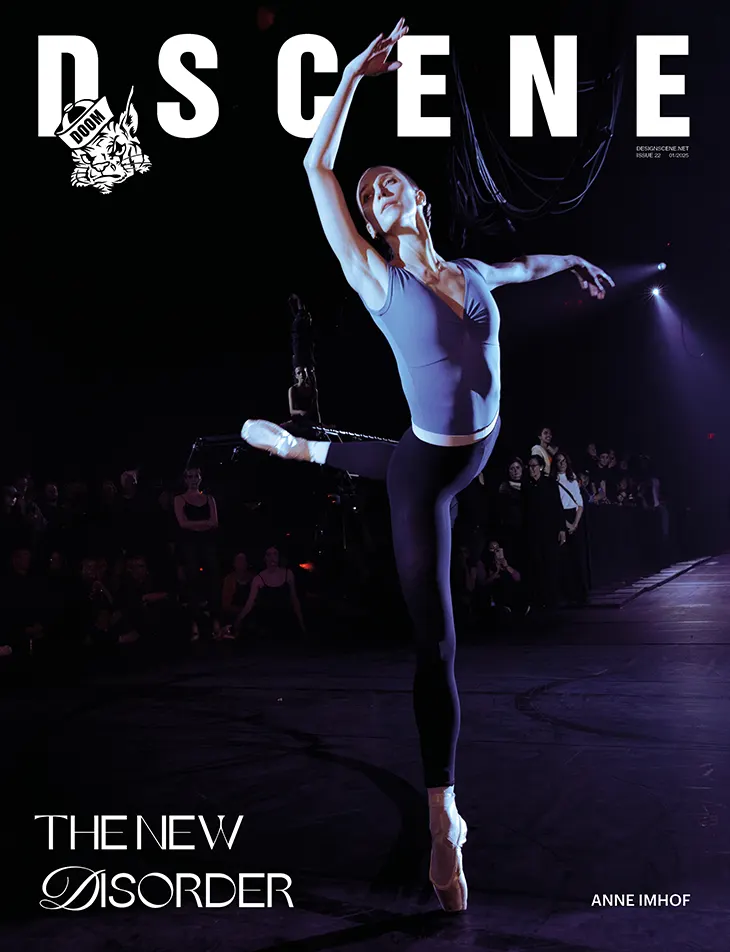

DSCENE Magazine reveals the cover of its The New Disorder Issue, designed by Anne Imhof, one of the most influential artists working today. Over the past decade, Imhof has reshaped how performance circulates between bodies, images, architecture, and power, producing works that refuse containment within a single medium. Her practice moves across performance, film, painting, drawing, and sculpture, yet always returns to the same core tension: exposure, control, vulnerability, and the politics of being seen. From early self-recorded videos to large-scale institutional commissions, Imhof has built a body of work that defines contemporary performance.

PRE-ORDER IN PRINT AND DIGITAL

That approach defines The New Disorder Issue cover, which Imhof designed using imagery from DOOM, her recent performance work. The cover image features American ballet dancer Devon Teuscher, photographed by Nadine Fraczkowski, bringing the work’s intensity into print and carrying its visual and emotional charge beyond the performance space. Drawn from DOOM’s internal system of exposure and surveillance, the cover compresses stage, camera, and viewer into a single visual condition.

Presented as DOOM House of Hope (2025), the work transformed the Drill Hall at Park Avenue Armory into a charged, prom-like arena layered with streamers, balloons, and Cadillac Escalades. Across three hours, dance, skating, music, and fractured scenes unfolded through a reverse retelling of Romeo and Juliet. Cameras occupied every corner. Performers carried them. Audience members raised them. Live feeds streamed to a Jumbotron. DOOM became its own system of watching, multiplying viewpoints until authorship itself felt unstable.

That instability anchors the in-depth interview included in The New Disorder Issue, a conversation between Imhof and Ian Forster for Art21. Forster entered DOOM with a film crew for Art21’s Extended Play series, adding yet another lens to an already saturated environment. Their exchange moves between rehearsal rooms and performance nights, between control and surrender, tracing how Imhof builds works that invite multiple subjectivities into the construction of an image.

“The only intention that I really have is to relinquish control,” Imhof says. “It’s a ridiculous enterprise to start controlling images and how they travel, in the same way that I find it ridiculous to control every maneuver and every movement of a four-hour piece where there are 40 cast members involved.” In DOOM, cameras shift from tools of documentation to instruments of power shared between performers and viewers. Images circulate before, during, and after the performance, shaping how the work becomes known.

Imhof traces this openness back to her earliest videos, filmed alone at night, often in her apartment. “The camera was a way to be seen by something; it was a way of seeing myself,” she reflects. Those early recordings, messy and urgent, laid the groundwork for a practice that treats documentation as material rather than residue. Later film works, she explains, must become “a completely different thing” in order to carry the charge of a performance forward.

The New Disorder Issue captures this continuum. Imhof’s cover image does what her performances do best: it refuses closure. It asks the reader to step inside a field of glances, bodies, and competing narratives, where meaning forms through proximity and friction. Alongside the full interview with Forster, the issue offers a rare look into how DOOM came into being and how Imhof continues to reinvent the conditions under which art is seen, shared, and remembered.