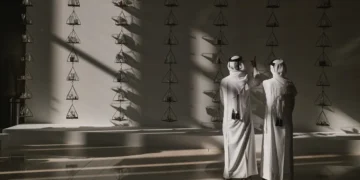

For artist Simon Mullan, image-making has never been limited to a single form. Whether cutting into subway tiles, reconstructing bomber jackets, or carving identity out of fabric and concrete, his practice has always circled the physical and the personal. In his solo exhibition chronos, which opened at DITTRICH & SCHLECHTRIEM on March 28, Mullan returned to a lesser-seen part of his archive: his early video works. Spanning footage recorded on MiniDV between 2004 and 2014, the exhibition presented a vast, unsynchronized network of moving images, looping endlessly across 25 screens.

INTERVIEWS

It was the first time the majority of these videos were shown in full, revealing the artist’s early explorations of performance, vulnerability, and collaboration. From his work with refugees in Vienna to scenes with individuals with special needs and his first performances in Stockholm, chronos laid bare a decade of raw footage that helped shape Mullan’s current language in sculpture and installation. In this exclusive DSCENE interview, Mullan reflects on the process of revisiting his younger self and the materials that continue to ground his work. The conversation touches on identity, power, public space, and the quiet moments that leave the loudest impressions.

Your upcoming exhibition features early video works, most of which have never been shown before. Why did you decide to present them now?

The videos were recorded between 2004 and 2014. Even back then, I had the idea of one day showing these images. Some of the videos have been exhibited before, but never in their original length. The decision to show them now is closely tied to the support of Dittrich & Schlechtriem, who are helping bring the concept of this exhibition to life.

Do these videos already show traces of themes or methods that later appear in your material-based works?

Absolutely. People familiar with my work will immediately recognize the connections, for example, how the idea of using bomber jackets as a symbol of subcultures developed.

How would you describe the difference between your early video-based practice and your current work with construction materials?

There’s no fundamental difference. Simply put, all I try to do is create images. In German, there’s a beautiful word: Bildhauer, which means “sculptor,” but literally translates to “image carver.” Behind all my work is an interest in people, whether it’s a working-class tiler (Tile Works) or a refugee from Nigeria (video work chronos).

Your work often merges rawness and precision, whether in tiles, workwear, or industrial materials. What draws you to these materials?

These are materials that surround us. Everyone grows up with tiles in their bathroom, and subway stations around the world are covered in them. I love that these materials are accessible to everyone and not expensive. As an art student, I learned about the Arte Povera movement, which fascinated me, the idea that you don’t need much to create something beautiful. A simple cut in a familiar tile can open up a new perspective.

How does your engagement with construction materials shape your perception of art and craftsmanship?

Textiles, on the other hand, naturally tell a story. They carry history within them. Clothing can be seen as a second skin, a form of communication in society. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea that by changing what you wear, you can change how people perceive you. I take these ideas and work with them in a simple, conceptual way.

“Simply put, all I try to do is create images. In German, there’s a beautiful word: Bildhauer, which means ‘sculptor,’ but literally translates to ‘image carver.’”

Can you recall a specific moment that sparked your interest in the relationship between art and working-class aesthetics?

No, there wasn’t a specific moment. I don’t think there is such a thing as a “working-class aesthetic.” People wear what feels good to them or what suits the occasion. A construction worker needs durable clothing, while an office job allows for a suit.

Your work explores class issues and representations of masculinity. Is it a tribute to manual labor, or a deconstruction of its myths?

I’ve always liked the idea of being a bridge between people who grew up with an interest in art and those who never had the opportunity or reason to engage with it. Art and, in a broader sense, culture, brings people together. It’s often the only thing left when everything else is lost.

Think of the millions of people forced to leave everything behind because of war, terror, or hunger. When all material possessions are gone, what remains are the songs they once learned, the poems they remember from school, or the artwork that lifts their spirits when they think of it.

Many of your pieces have a strong physical presence. How important are tactility and materiality to you compared to concept and symbolism?

I can’t fully explain where my desire to create comes from, perhaps it’s the wish to make something minimal, something beautiful. My older sister had a big influence on me. She’s a graphic designer, and in some ways, I always wanted to be a little like her.

If you look at my work with workwear, the so-called Blaumänner, of course, I love the color blue. But it was the concept behind it that led me to create blue works, not the other way around.

“Think of the millions of people forced to leave everything behind because of war, terror, or hunger. When all material possessions are gone, what remains are the songs they once learned, the poems they remember from school, or the artwork that lifts their spirits when they think of it.“

What role does public space play in your art, both as a physical location and as a social stage?

I love public art. It’s free, and it’s for everyone. I remember seeing public sculptures as a child and wondering: Who made this strange-looking thing, and why? Public art is a gateway for people who might not have the privilege of growing up in a household that visits galleries and museums.

Now that you’ve revisited your own video archive: Is there anything your younger self has taught you?

At times, it was humorous. At other times, it was difficult to look through so much recorded material from the past. Of course, it was also a process of reflection. I realized that I used to be fearless, unconcerned about what others thought of me. This exhibition marks my ambition to reconnect with that feeling.