When Virginie Viard quietly exited Chanel and Maria Grazia Chiuri stepped down from Dior, the news didn’t just mark the end of two creative tenures, it marked a near-total erasure of women from the top of luxury fashion. In their place, Matthieu Blazy took over at Chanel, and Jonathan Anderson was announced at Dior. They join an already male-dominated pantheon: Demna at Gucci, Michael Rider at Celine, Alessandro Michele at Valentino, Pieter Mulier at Alaïa, and the list goes on. It’s not a trend. It’s a system.

Fashion, the industry that sells female aspiration as profit, now finds itself in a creative leadership structure that looks almost indistinguishable from 1995. Except in 1995, one might have hoped we were heading somewhere else. Instead, the glass ceiling hasn’t just remained intact, it’s been polished, reinforced, and repackaged as creative genius.

There is a tired phrase that always gets wheeled out when these appointments are made: “He was the most qualified candidate.” That may be true in some narrow, internal way, but the very structures that determine who becomes “qualified” are built on longstanding inequities. Who gets to shadow the current creative director? Who is seen as a visionary? Who is allowed to fail upwards?

Luxury fashion’s hiring logic is recursive. The creative directors of today, nearly all men, choose their deputies and protégés, who then go on to become the directors of tomorrow. Women are rarely chosen as second-in-command. And when they are, they are often burdened with proving not only their individual skill but their right to exist in the space at all.

It’s no coincidence that the few women at the helm of major houses, Chiuri, Viard, Chemena Kamali, Veronica Leoni, Silvia Venturini Fendi, had to spend years working within the brand or under a male predecessor before being considered. Male designers, meanwhile, continue to be parachuted in with bold mandates and immediate creative carte blanche.

The industry likes to frame these hires as bold pivots, “visionary” men coming in to shake things up. But what’s really happening is a reversion to a familiar formula: give a man the power to create a spectacle, surround him with a marketing machine, and watch the numbers (hopefully) rise. It’s a high-stakes gamble, often fueled by nostalgia for the auteur-designer figures like Galliano, McQueen, and Lagerfeld.

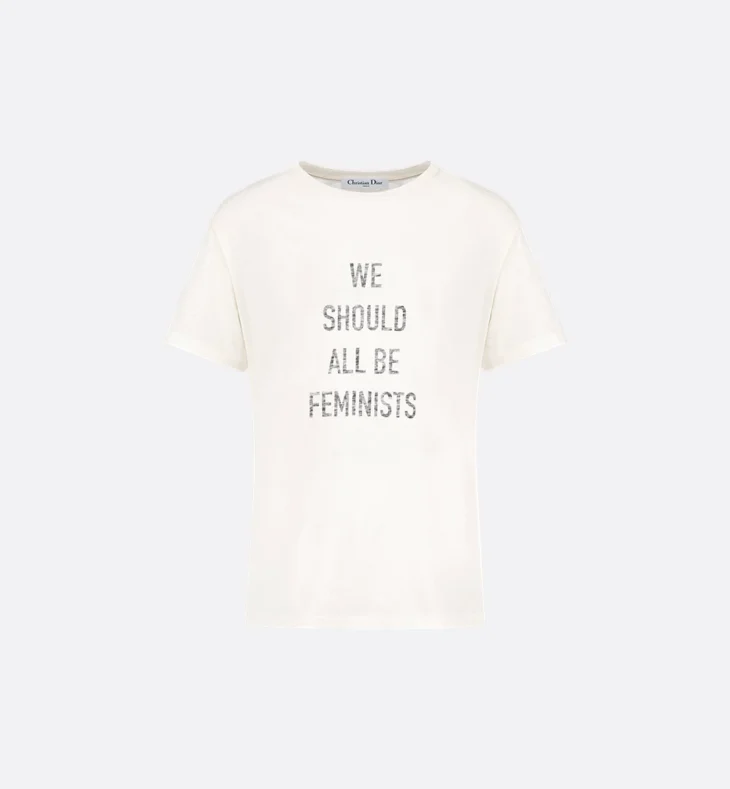

But what gets lost in this narrative is the quieter revolution that women have long been carrying out. Maria Grazia Chiuri may not have produced headline-grabbing collections every season, but under her leadership Dior posted record-breaking growth and a cultural relevance anchored in feminism, community, and craftsmanship. Her introduction of the “We Should All Be Feminists” T-shirt was a signal that fashion could speak directly to women, not just about them.

Viard, too, offered something that the industry failed to value. Her work at Chanel was understated, sometimes uneven, but always deeply in tune with the house’s codes and the lives of its real customers. She resisted the maximalist theatrics that had become a Chanel signature under Lagerfeld, focusing instead on intimacy and wearability. She didn’t dress the fantasy, she dressed the woman. And that was never enough.

There’s a condescending assumption in fashion that designing for women is somehow less creative than conceptual menswear or androgynous spectacle. But dressing women, understanding their real lives, ambitions, insecurities, and needs, requires more than just technical skill. It requires care, curiosity, and respect. These are qualities often devalued in an industry that fetishizes the avant-garde over the functional, the statement over the subtle.

The return to a male-dominated roster also threatens to narrow the scope of reference. It’s not that men can’t design for women, it’s that they tend to design through the lens of fantasy, often filtered through desire, power, or nostalgia. What’s missing is lived experience. When women helm houses, the tone changes. The clothes often become tools of autonomy, not costumes of seduction.

Let’s not ignore the economics. The return of men to top roles coincides with a retail crisis. Fashion houses are struggling. Prices have surged up to 59% at Chanel between 2020 and 2023. Customers are fatigued, disillusioned, and increasingly skeptical of the value proposition. In this context, appointing men is not only about legacy, it’s about risk tolerance. Big budgets, big ideas, and big expectations.

And yet, the previous era of female leadership was marked by consistency and steady growth. Chiuri’s Dior, for instance, became one of LVMH’s crown jewels. But in the eyes of executives and critics, her commercial success was often reduced to “safe,” “repetitive,” or “uninspired.” As if profit-driven creativity is somehow lesser when helmed by a woman.

This double standard has long plagued the industry. Women are expected to be pragmatic, balanced, and responsible stewards of a brand. Men are allowed to be mercurial geniuses, even when their work falters. One set of rules governs both.

Some will point to Chemena Kamali at Chloé or Veronica Leoni at Calvin Klein Collection as proof that women are not being excluded. But these appointments are the exception, not the rule, and they tend to occur at brands looking to repair or reset their image, not brands in positions of power.

Moreover, women in these roles often carry the burden of representation. Their work is scrutinized not just on its own merit but for what it signals about the broader culture. A successful collection is never just fashion, it becomes a referendum on all women in creative leadership. Until multiple women can succeed, fail, experiment, and take risks without being turned into symbols, parity will remain elusive.

Executives frequently cite the lack of female creative directors as a pipeline issue. “There just aren’t enough women in senior roles,” they say. But this is a self-inflicted problem. If brands don’t cultivate female talent, through mentorships, visibility, and real creative ownership, how can they expect them to magically appear when it’s time to make a hire?

And let’s be clear: there are women ready. Marine Serre, Iris van Herpen, Thebe Magugu, Nensi Dojaka, and many more have carved out distinctive design languages. Many have proven themselves commercially viable and critically acclaimed. Yet when the top jobs open up, their names are rarely in the mix. It’s not that the talent doesn’t exist. It’s that the power does not recognize it.

If fashion wants to maintain relevance, it must confront its comfort with male dominance. That means interrogating hiring processes, dismantling internal hierarchies, and truly investing in female talent at every level. It means understanding that leadership doesn’t always look like Karl or Hedi or Demna.

It also means broadening the conversation. Where are the Black women in leadership? Where are the trans designers? Where are the creative directors whose lived experiences represent the customers being marketed to? The lack of gender parity is just one symptom of an industry deeply disconnected from the realities it claims to reflect.

Fashion cannot continue to market empowerment while practicing exclusion. It cannot sell feminism on a T-shirt and silence women at the table. And it cannot, in good faith, pretend that this latest round of musical chairs is anything but a regression, disguised as evolution.

Until women are allowed to lead, fail, return, and rise again, just like their male peers, fashion will remain a men’s game, played on women’s bodies.