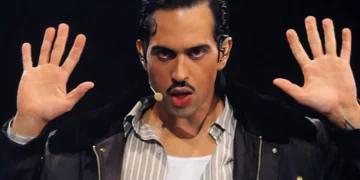

Once designed to signal authority, conformity, and control, the uniform has long served as a visual shorthand for power. But in the hands of today’s emerging designers, it’s being completely rewritten. Across runways, studios, and Instagram grids, a new generation is reclaiming and reconfiguring what it means to dress for power. Their approach is less about hierarchy and more about expression; less about rigidity and more about disruption. This is not the power suit of the boardroom – it’s the chaotic, often genderless, sometimes undone reinterpretation of it.

FASHION

From Tokyo to Tbilisi, fashion schools to bedroom brands, the new uniform is surfacing everywhere: reconstructed blazers with asymmetrical lapels, trousers with unexpected slits or skirts layered over mesh bodywear, and jackets that deliberately resist the structure they once stood for. These garments don’t reinforce systems, they question them.

The Collapse of the Old Codes

The classic power dressing, shoulder pads, cinched waist, crisply tailored trousers, was once a reliable indicator of seriousness, especially for women navigating male-dominated environments. Designers like Giorgio Armani in the 1980s understood the psychological armor it offered. But in 2025, the idea of dressing to assimilate feels out of step with a generation raised on defiance and deconstruction.

Today’s young designers are turning those old codes inside out. They aren’t interested in “dressing for the job you want.” They’re dressing to expose the absurdity of those jobs, the fragility of those institutions, the hollowness of performative professionalism. Suits are slashed open, buttons are moved off-center, and garments are left intentionally incomplete.

Genderlessness as Power

Perhaps the most radical element of this shift is its indifference to gendered dress codes. Power dressing, once deeply tied to ideas of masculinity, whether emulated or subverted, is now being queered beyond recognition. Brands like Ottolinger, Talia Byre, Chet Lo, S.S. Daley and Mowalola create collections that don’t trade in binary opposition but fluid multiplicity. A blazer is no longer “menswear” or “womenswear” – it’s just a starting point.

In the work of Berlin-based designer Gerrit Jacob, for instance, a bomber jacket might be paired with sheer tights and embroidered cowboy boots. In London, Paolo Carzana layers flowing, hand-dyed silks with militaristic details, creating silhouettes that feel at once soft and armored. These juxtapositions challenge assumptions about what authority should look like, and who gets to hold it.

The new uniform doesn’t flatten identity – it stretches it. In doing so, it reveals how deeply embedded our notions of professionalism, beauty, and respectability are in traditional ideas of gender. To reject those structures is to dress in resistance.

From Workwear to Clubwear

Another key thread in this evolution is the blurring of professional and personal spheres. Many of these young designers draw as much from rave culture, DIY style, and nightlife as they do from tailoring traditions. There’s a growing tendency to reimagine the office uniform through the aesthetics of the underground. It’s no coincidence that brands like KNWLS or NAMESAKE show tailored pieces alongside corsetry, mesh layers, or motocross-inspired gear.

Take New York-based label Commission, whose reinterpretation of 1990s East Asian officewear leans heavily into nostalgia, softness, and restraint. The garments nod to bureaucracy, but they also reframe it, imbuing the mundane with sensuality, complexity, and contradiction.

The hybridization of workwear and clubwear reflects the reality of a generation that sees no clear separation between labor and life. They freelance from bed, brainstorm in bars, and DJ on weekends. Dressing for this reality requires clothing that can shift contexts, subvert them, and sometimes mock them altogether.

Materials That Speak

Textiles have always carried social meaning, and the new wave of designers uses them to speak loudly. Leather, once reserved for outerwear or rebellion, now appears in fluid trousers and asymmetrical tops. Sheer fabrics are layered under pinstripes, creating a dynamic between exposure and concealment. Technical fabrics usually reserved for performance gear are used in blazers and dress pants, offering movement, subverting tradition, and confusing context.

Sustainability also factors heavily into this equation, not just as a marketing angle, but as part of the subversive logic of the uniform. By using deadstock fabric, reworking vintage suits, or upcycling discarded workwear, designers critique the overproduction at the heart of capitalist systems. In many cases, the very materials used are leftovers from the systems these garments aim to dismantle.

The Influence of Institutions

(and the Rejection of Them)

While many young designers pass through fashion institutions like Central Saint Martins or the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, their post-graduate work often stands in direct opposition to what they were taught. There is a growing irreverence toward fashion’s institutional structures, its reliance on legacy houses, seasonal shows, and commercial polish.

Instead, these designers are embracing irregular timelines, unconventional casting, and guerrilla-style presentations. Their collections are less concerned with retail viability and more with creating a moment, a mood, or a message. And often, that message is: we do not want to fit in.

This ethos is amplified on social media, where aesthetics are no longer filtered through industry gatekeepers. The new uniform is not something that waits for approval, it’s something you wear into the world and document yourself.

Dressing for Power on Your Own Terms

At its core, this shift in power dressing is about agency. It asks: what does it mean to dress for power if power itself is shifting? In the wake of political uncertainty, economic instability, and climate crisis, many in this generation no longer aspire to climb institutional ladders. They want to build new structures altogether, or burn down the old ones.

For them, the uniform is not a way in. It’s a way out.

Power, in this context, is no longer conferred by titles, salaries, or tailoring. It’s in the refusal to perform respectability. It’s in the way a frayed hem can say more than a polished cuff. It’s in the act of wearing something that makes no sense to anyone but you.

This is the new uniform. Unfinished, unpolished, unbothered, and all the more powerful for it.